A Conversation with Everardo González (DROUGHT)

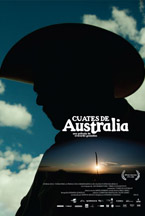

Mexican filmmaker Everardo González is emerging as one of the leading lights in Latin America’s thriving documentary scene. Drought (original title: Cuates de Australia), his fourth feature-length documentary, is having a stellar festival run, premiering at the prestigious IDFA in Amsterdam and picking up a Grand Jury Award at the LAFilmFest, amongst many other screenings. The film follows a community of ranchers on a dry and remote stretch of land called Cuates de Australia, in Coahuila, Mexico, working tirelessly to survive as their water dries up. It’s a stunning movie—González goes far beyond reportage, approaching film more like a visual artist or musician than a journalist, and yet Drought has a powerful narrative sweep and a huge, cathartic conclusion. [Read the full H2N review here]

Mexican filmmaker Everardo González is emerging as one of the leading lights in Latin America’s thriving documentary scene. Drought (original title: Cuates de Australia), his fourth feature-length documentary, is having a stellar festival run, premiering at the prestigious IDFA in Amsterdam and picking up a Grand Jury Award at the LAFilmFest, amongst many other screenings. The film follows a community of ranchers on a dry and remote stretch of land called Cuates de Australia, in Coahuila, Mexico, working tirelessly to survive as their water dries up. It’s a stunning movie—González goes far beyond reportage, approaching film more like a visual artist or musician than a journalist, and yet Drought has a powerful narrative sweep and a huge, cathartic conclusion. [Read the full H2N review here]

I arrive early at the restaurant of the Beverly Garland Holiday Inn in North Hollywood; González is already there. It’s just a diner, and far from packed, but ordering nothing but coffee creates a somewhat comical tension with the wait-staff.

González is in L.A. for the week-long run of Drought at DocuWeeks; he has a serious manner but occasionally breaks into a big, boyish smile. He’s friendly and confident and likes to look out the window to focus his thoughts as he speaks. He has a habit of checking in, by ending sentences with a “yeah?” or a “no?” When we talk about Mexico he frequently uses the term “narcs”—it’s how he translates “narcos,” the word used in Mexico for the armies of organized drug traffickers fighting in the brutal drug wars.

Hammer to Nail: Just to start off, how did you first find out about Cuates de Australia and become interested in this subject?

Hammer to Nail: Just to start off, how did you first find out about Cuates de Australia and become interested in this subject?

Everardo González: In 2004 I was directing a television doc. It was about history, a really boring topic, but fortunately that series of docs gave me the chance to travel around the country and visit really quite peculiar places, just like Cuates de Australia, the ranch where Drought happens, yeah? So I was there in 2004 making this television thing, and there was an old cowboy who asked me if I wanted to visit a ranch called Cuates de Australia, which was in the high part of the sierra. And then, you know, if you make a living with docs, a place like that is a huge magnet for visiting, yeah? So I decided to follow this guy, and when I arrive, the whole landscape is extraordinary, I mean the whole trip for making it to Cuates de Australia. It’s a very isolated ranch and there are no really good roads; actually there is only one… kind of a road. They have no communications, no electricity. But then I found out a place in the middle of nowhere with a lot of quite interesting people. That’s when another guy told me—I approached him and I started to ask him how do they make a living, how are the problems of community? And then this guy told me the story about an exodus that every year they have to make in order to escape from drought, and they were always waiting for the rains, yeah? So this thing about a town and a group of people who lives waiting for the rain was something in my opinion really poetic. It was a great metaphor about hope. But also the same atmosphere and the same problem about drought is death. So in my opinion they were a kind of a town that each year had to hide from death and then wait for the rain to come back because when the rain comes death leaves the place. So it was really cinematic, the story. That idea I kept in mind for three years and then in 2007 I started the shooting of the film.

H2N: We see a lot of documentaries of this kind that come from a developed world perspective, where you have a sense of pity for the subjects, a sense that we need to help these people. Your doc seems to be interested in how they see the world and how they do not see themselves as victims.

EG: Well that’s an important thing in my opinion. I don’t like this feeling that most documentary filmmakers have about becoming heroic figures, yeah? That also anthropologists have in a sense, you know? Discover a lot of things for the world… And a lot of documentarians are activists more than filmmakers. In my opinion I am only a filmmaker, not an activist. If the film is able to change things then it’ll be great, but if it doesn’t we have to work in order to have a better film, in the service of cinema. So when I got there I had, you know, the same worry that you are telling me, because actually it’s a kind of a really poor community, a real emarginated place, but on the other hand because of that they have a lot of freedom that we do not know, yeah? They live in a very dangerous area, because it is taken by the narcs, but in the highlands, because it doesn’t rain at all, it’s a land that no one cares about, not even the narcs. So they really do not care if the narcs are here, or at the border if we have migration problems, or we have misery, because they told me that they realize that they are poor when they are in town. When they are at the ranch they do not realize that they are poor. They don’t even think about it. So I started to understand those things, living there. For example there’s a big issue with education; people want everyone to study what we think is worthwhile for them, yeah? But then a kid told me that the only thing he wanted to become was a better cowboy—then I understood also that it’s okay to become a scientist, but we also need cowboys in our society, no? And this kid was right. It was really an aspirational thing for him to become a better cowboy, just like for another kid maybe to become a lawyer. Because in a way a cowboy is more useful in their community than a lawyer, yeah? So then I started to think. And enjoy the time with them. And I found all this beautiful freedom they have, in a way, and the beautiful things they enjoy, and I started to learn with them about the joy of the minimal things. Because my own story there started with a small bed, terrible place, cold, alone, but then when production started and we had four beds for the crew, a stove, a clean house—it was everything we needed. So then we started to live with nothing, and enjoy those things, and that’s a feeling that I had to show. Not the misery of it, but the joy of the place, in spite of the desert. Because that’s another beautiful thing about the place: it’s so gorgeous, you can drop the camera and you will have a beautiful fixed frame. So it’s tricky, I think, to shoot in the desert. But on the other hand it’s really a hostile place, and the conditions for life are really something aggressive. And then that’s something I wanted to show, and if I wanted to show this duality of life then I had to show a very hostile place with very happy people, yeah? So in a way there’s always this fight with man and the environment in order to see who will rule, and that’s something I wanted to show in the film. When they leave, now it’s the time for nature. Nature is the one that takes control of the town, yeah? Later, when the people come back, everything goes in the usual way. It was almost impossible for me to make a film about pity, because these people will not allow you to shoot them with pity. They are really kind people. They are tough, but they are really kind also in a way. Kids, for example—you cannot ask the people in a gentle way to leave the place because you are tired, because they will get offended. You must be rude with them and they will run, and it’ll be okay. The same with the other guys. So they are rude in a way but they are really gentle also. Just like the desert, that is something interesting that happened there; that’s something I wanted to show. If I would have made a film about pity and sorrow, then it would be like I was in guilt for society, no? “These people are living with nothing and you are wasting…” It’s like a father that’s always, I don’t know the word in English but we call it “chantaje,” you know. Blackmailing. Blackmailing the audience, and I don’t like to do this. We’re making a film, not a social study, not an activism, no. It’s not an eco-film, even though it could be used as an eco-film, but it was not a main goal.

EG: Well that’s an important thing in my opinion. I don’t like this feeling that most documentary filmmakers have about becoming heroic figures, yeah? That also anthropologists have in a sense, you know? Discover a lot of things for the world… And a lot of documentarians are activists more than filmmakers. In my opinion I am only a filmmaker, not an activist. If the film is able to change things then it’ll be great, but if it doesn’t we have to work in order to have a better film, in the service of cinema. So when I got there I had, you know, the same worry that you are telling me, because actually it’s a kind of a really poor community, a real emarginated place, but on the other hand because of that they have a lot of freedom that we do not know, yeah? They live in a very dangerous area, because it is taken by the narcs, but in the highlands, because it doesn’t rain at all, it’s a land that no one cares about, not even the narcs. So they really do not care if the narcs are here, or at the border if we have migration problems, or we have misery, because they told me that they realize that they are poor when they are in town. When they are at the ranch they do not realize that they are poor. They don’t even think about it. So I started to understand those things, living there. For example there’s a big issue with education; people want everyone to study what we think is worthwhile for them, yeah? But then a kid told me that the only thing he wanted to become was a better cowboy—then I understood also that it’s okay to become a scientist, but we also need cowboys in our society, no? And this kid was right. It was really an aspirational thing for him to become a better cowboy, just like for another kid maybe to become a lawyer. Because in a way a cowboy is more useful in their community than a lawyer, yeah? So then I started to think. And enjoy the time with them. And I found all this beautiful freedom they have, in a way, and the beautiful things they enjoy, and I started to learn with them about the joy of the minimal things. Because my own story there started with a small bed, terrible place, cold, alone, but then when production started and we had four beds for the crew, a stove, a clean house—it was everything we needed. So then we started to live with nothing, and enjoy those things, and that’s a feeling that I had to show. Not the misery of it, but the joy of the place, in spite of the desert. Because that’s another beautiful thing about the place: it’s so gorgeous, you can drop the camera and you will have a beautiful fixed frame. So it’s tricky, I think, to shoot in the desert. But on the other hand it’s really a hostile place, and the conditions for life are really something aggressive. And then that’s something I wanted to show, and if I wanted to show this duality of life then I had to show a very hostile place with very happy people, yeah? So in a way there’s always this fight with man and the environment in order to see who will rule, and that’s something I wanted to show in the film. When they leave, now it’s the time for nature. Nature is the one that takes control of the town, yeah? Later, when the people come back, everything goes in the usual way. It was almost impossible for me to make a film about pity, because these people will not allow you to shoot them with pity. They are really kind people. They are tough, but they are really kind also in a way. Kids, for example—you cannot ask the people in a gentle way to leave the place because you are tired, because they will get offended. You must be rude with them and they will run, and it’ll be okay. The same with the other guys. So they are rude in a way but they are really gentle also. Just like the desert, that is something interesting that happened there; that’s something I wanted to show. If I would have made a film about pity and sorrow, then it would be like I was in guilt for society, no? “These people are living with nothing and you are wasting…” It’s like a father that’s always, I don’t know the word in English but we call it “chantaje,” you know. Blackmailing. Blackmailing the audience, and I don’t like to do this. We’re making a film, not a social study, not an activism, no. It’s not an eco-film, even though it could be used as an eco-film, but it was not a main goal.

H2N: You have these amazing images—especially the sky over the location—but it doesn’t feel like you were looking for pretty images, so how did you approach your cinematography?

EG: I’m gonna give you an example. There is a sequence where there is a sandstorm coming, which happens to be the previous sequence to the beginning of the rain, yeah? When I was there shooting that sandstorm I had a feeling that something terrible was gonna happen, but then what happened was rain! So in a way that’s a beautiful thing that I discovered there. Life always comes in a violent way. Giving birth, it’s something really violent. And death is always really calm and peaceful when it arrives, no? Not with a violent action, but death will always come in a quiet route, and birth will always come in a violent way. So I decided to make the landscape with that idea, of showing that sandstorm. For example there’s a sequence where there are people working in the fields and there’s a boy talking about why he didn’t make it to school, and then you see a snake close to them, yeah? It’s always the presence of death, or danger in the place even though it is beautiful. So I decided for example the coyote—the coyote is not only wild. It’s the presence of death also in a way, no? Because it is always approaching and approaching and approaching the town, and once death arrives with the drought it is a moment for coyotes. So we decided, me and this director of photography that specializes in wildlife, to choose the coyote as that image, so we decided that the coyote was an important animal to track, not the rest of them, even though we were finding some of them. And the same with landscapes. It was not only about beautiful sunsets or beautiful landscapes, it was about trying to show the isolation of the place, trying to show the heat of the place, and trying to show also the tragedy that was going on as the dirt was drying and drying and drying. I hope we made it, to show that feeling, because as I tell you it is easy to have a beautiful landscape, especially in the desert.

EG: I’m gonna give you an example. There is a sequence where there is a sandstorm coming, which happens to be the previous sequence to the beginning of the rain, yeah? When I was there shooting that sandstorm I had a feeling that something terrible was gonna happen, but then what happened was rain! So in a way that’s a beautiful thing that I discovered there. Life always comes in a violent way. Giving birth, it’s something really violent. And death is always really calm and peaceful when it arrives, no? Not with a violent action, but death will always come in a quiet route, and birth will always come in a violent way. So I decided to make the landscape with that idea, of showing that sandstorm. For example there’s a sequence where there are people working in the fields and there’s a boy talking about why he didn’t make it to school, and then you see a snake close to them, yeah? It’s always the presence of death, or danger in the place even though it is beautiful. So I decided for example the coyote—the coyote is not only wild. It’s the presence of death also in a way, no? Because it is always approaching and approaching and approaching the town, and once death arrives with the drought it is a moment for coyotes. So we decided, me and this director of photography that specializes in wildlife, to choose the coyote as that image, so we decided that the coyote was an important animal to track, not the rest of them, even though we were finding some of them. And the same with landscapes. It was not only about beautiful sunsets or beautiful landscapes, it was about trying to show the isolation of the place, trying to show the heat of the place, and trying to show also the tragedy that was going on as the dirt was drying and drying and drying. I hope we made it, to show that feeling, because as I tell you it is easy to have a beautiful landscape, especially in the desert.

H2N: I also found your editing really interesting, for example the cut from the horses procreating to the human couple getting the ultrasound, along with the element of the boy telling the story of the devil’s horse, and the folk song—it’s not a simple juxtaposition; there are all these layers of ideas…

EG: Of meaning, exactly. For example we have this story about the devil. In the beginning where there’s a horse procreating, there’s a kid telling a story about a devil’s horse. But then when the storm is gonna come we go once again to a story of a devil cow. So the devil is always in the presence of the people, yeah? And for me there was a very brutal image, this horse. Because, as I told you, giving life is something violent and brutal. It’s beautiful but it can be violent also. So that was the image and then the idea was that the woman was fertilized by the horse, in a way. Because there will be like a horse town in a way. And they have a really tight connection between the animals, the fields, and the human beings. I had this image that I saw but I never shot it and it’s a pity. There was this lake, this pond, and it was really hot when I was there once, and there was a coyote drinking water and on the other side there was a horse, and on the other one there was a man drawing water out, so there I always thought about the connection we have, through water, and that was a feeling I wanted to show. And we had these layers—for example the film is about hope and I think that the most important hope in human life is to bring new life. A new human being is what we people are always waiting for. Even if we don’t want to become fathers. Because that’s something that we humans are always waiting for—the re-birth of families, the re-birth of things. And in the environment they are waiting for the rain because it will give re-birth, so that sequence especially, that sequence is like kind of a synopsis of what the film will be about in the next 85 minutes, which are the layers of the film—of death, about this duality between death and rebirth and hope and everything surrounding it. And this music is a beautiful music, sung by a trio in that area, which is kind of blues of the most painful—you can feel it in the way they sing it, so in a way it gives a great atmosphere to what is going on there. Because music is something beautiful but it’s painful at the same time. And the structure was in a way simple. We had to talk about a town that was drying out, a town that’s waiting for the rain, and that gives you a pretty solid structure, yeah? You know that you have to edit in order to be storytelling: the beginning of the drought, and then people have to leave; waiting for the rain, and then rain will bring life. So structurally it’s pretty simple. I mean the sequences maybe are where we try to have more complexity, in the writing of it, but the structure is simple.

H2N: How long was the production of the film?

EG: It was four years. Three years of shooting and one year for editing and post-production. First year I was traveling myself only with a camera because I really didn’t shoot too much. I made in three years only 45 hours to make the whole cut. So the first year was just to understand what I was doing there, what was the story there; letting the people know me and the chance for me to get to know the people. The most important thing is to be accepted in the community, you know. So I worked on that in the first year, always traveling alone, in order to establish contacts and make friends and, you know, to open doors. When I had those things then a production coordinator traveled, and a sound man, and we started shooting, now in a more professional way, yeah? And then things were happening because we were traveling chasing the rains. Which was in my opinion something beautiful as an experience, because the timeline and the timetable of the film was always wondering when the rains will begin. So it was a much more beautiful thing to have a timetable that was tied to that thing, not because of the money or the fundraising, and so then we started to travel. But there were times that we were waiting for the rain and then drought arrived. And we were waiting for drought and rain came. So it was really kind of—we were a little bit blinded to what was going on then. So that’s why it took so long. In a way it helped because people could have the time to know us, to collaborate with us, to become more participative, and make their own film in a way, no? They started to make suggestions, they started to make love with our film. It was good, it was three years of shooting.

EG: It was four years. Three years of shooting and one year for editing and post-production. First year I was traveling myself only with a camera because I really didn’t shoot too much. I made in three years only 45 hours to make the whole cut. So the first year was just to understand what I was doing there, what was the story there; letting the people know me and the chance for me to get to know the people. The most important thing is to be accepted in the community, you know. So I worked on that in the first year, always traveling alone, in order to establish contacts and make friends and, you know, to open doors. When I had those things then a production coordinator traveled, and a sound man, and we started shooting, now in a more professional way, yeah? And then things were happening because we were traveling chasing the rains. Which was in my opinion something beautiful as an experience, because the timeline and the timetable of the film was always wondering when the rains will begin. So it was a much more beautiful thing to have a timetable that was tied to that thing, not because of the money or the fundraising, and so then we started to travel. But there were times that we were waiting for the rain and then drought arrived. And we were waiting for drought and rain came. So it was really kind of—we were a little bit blinded to what was going on then. So that’s why it took so long. In a way it helped because people could have the time to know us, to collaborate with us, to become more participative, and make their own film in a way, no? They started to make suggestions, they started to make love with our film. It was good, it was three years of shooting.

H2N: Did you get valuable suggestions from them?

EG: Of course. For example there is this image of a horse, a small horse that dies, because they ran and told me, “There’s an ill horse, it will help for the film,” and then we went. He didn’t die at the scene; they had to sacrifice the horse, but I knew when I was shooting it that it would help with the film, because we couldn’t do anything—the horse was gonna die. So I left the camera, and the horse only fell down, so then we cut to the coyote, yeah? The horse didn’t die in that moment; we had to wait around. Then the vets tried to help him, and then the other guys tried to help him, but it was nonsense, they had to sacrifice the horse. But it was because they were always running and telling me, “You have to come here, there’s a new nest of crows in the rocks, on the hill,” or, “You gotta come here, we’re gonna have a race—there’s gonna be a horse race next week, you should come here.” So in a way they were advising when and where it would happen. For example there’s another beautiful thing they told me: I do not explain it, but at least in sound I wanted to. There’s a moment when the coyotes are eating the dead donkey and they started to listen to something and there’s the singing of the frogs starting to go up and up and up and up, because they told me for example that when the frogs start to sing it’s because rain is coming. So they don’t look for the clouds; they also listen to the frogs. So I put it there and it’s not something that you will understand, but it helps in order to put tension a little bit, only with sound, yeah? So there were suggestions these cowboy filmmakers did give me—there were a lot of them.

H2N: Your film is sort of shot in verité style, but at the same time people do acknowledge the camera; did you think about that specifically, or did you just let it happen…?

EG: Well I do let it happen, because I’m not an activist, really. I don’t want people to believe that what they are seeing is the truth, no? So I always try—it’s just the way it goes during the shooting. For me the other way is kind of a dogma, yeah? Really dogmatic and it does not allow you to construct a lot of things nowadays, no? Verité had its own time, in my opinion; it had its time before. So now it’s a mixture of everything. Sometimes it’s good to let people know they’re watching a film. Because that gives you a lot of freedom. You know, for example the drought was in the first year. The rain came in the last year. But it helps you to construct without trying to be following reality’s timetable. But to use the film’s timetable. For example one guy screams, or yells at another one—shot it in January. And then the one who turns his back, answering the other guy, we shot him in November. So, it’s cinema, yeah? It’s cinema. So sometimes it’s good to put those things, for example this little horse—he didn’t die because of the dryness of things. He died because of other things. But in the film he had to die because of the drought. If I was always concerned about trying not to—trying to forget that we have a camera—they will always be aware of a camera. It’s kind of pretentious to think that the camera will not manipulate and will not affect the whole environment. It’s a huge event. A camera is a huge event for these people. You are fooling with the camera there; you cannot ask them to not realize that you are there with them. And in a way that shows also the connection with the crew and the people. When there’s a kid taking a bath and he calls me by my name it’s great in a way because it sets a connection between the crew and—but it’s always a crew behind the film. If not, trying to push style is for me very complicated. It probably could be made with this style but it’s not something that I’m chasing. I prefer to get the stories. Instead of putting in, “This style is the one that will define me.” Because you will always betray yourself when you do those things. Even the Maysles had those problems. Errol Morris, all those beautiful talking heads films, but also more like—this one of the cemetery, what is the name of it? [Gates of Heaven] It’s quite a different film. So it’s always good to be changing I think.

EG: Well I do let it happen, because I’m not an activist, really. I don’t want people to believe that what they are seeing is the truth, no? So I always try—it’s just the way it goes during the shooting. For me the other way is kind of a dogma, yeah? Really dogmatic and it does not allow you to construct a lot of things nowadays, no? Verité had its own time, in my opinion; it had its time before. So now it’s a mixture of everything. Sometimes it’s good to let people know they’re watching a film. Because that gives you a lot of freedom. You know, for example the drought was in the first year. The rain came in the last year. But it helps you to construct without trying to be following reality’s timetable. But to use the film’s timetable. For example one guy screams, or yells at another one—shot it in January. And then the one who turns his back, answering the other guy, we shot him in November. So, it’s cinema, yeah? It’s cinema. So sometimes it’s good to put those things, for example this little horse—he didn’t die because of the dryness of things. He died because of other things. But in the film he had to die because of the drought. If I was always concerned about trying not to—trying to forget that we have a camera—they will always be aware of a camera. It’s kind of pretentious to think that the camera will not manipulate and will not affect the whole environment. It’s a huge event. A camera is a huge event for these people. You are fooling with the camera there; you cannot ask them to not realize that you are there with them. And in a way that shows also the connection with the crew and the people. When there’s a kid taking a bath and he calls me by my name it’s great in a way because it sets a connection between the crew and—but it’s always a crew behind the film. If not, trying to push style is for me very complicated. It probably could be made with this style but it’s not something that I’m chasing. I prefer to get the stories. Instead of putting in, “This style is the one that will define me.” Because you will always betray yourself when you do those things. Even the Maysles had those problems. Errol Morris, all those beautiful talking heads films, but also more like—this one of the cemetery, what is the name of it? [Gates of Heaven] It’s quite a different film. So it’s always good to be changing I think.

H2N: So would you say that’s the context your work comes from? From studying classic documentaries?

EG: For example I’m gonna tell you about another film that I had before. It’s a story about thieves. Ethical thieves in Mexico, yeah? So they start to tell you how they learned, from whom, which are the ethical codes they had to take care of, how they used to rob, how many minutes or seconds they had in order to get inside a house, steal everything and leave without making physical harm to anyone. There’s this beautiful character which is kind of a cynic, you know? A thief that robbed two presidents in Mexico. And he tells you the story how. If I would have been pushing for the verité style then I would lose a great storyteller, yeah? And a great story. If I had to push style and say, “No I don’t want testimony, I only want images,” I would’ve had a film in prison, and there are lots of films shot in prisons. Sometimes if he’s telling the story then you can imagine also how it was. And if you have a great storyteller then it’s worth it to use his testimony as part of the structure. In this case the whole situation helped a lot. In my first film I did the same as in this last one. And I have two in the middle with testimonials, talking heads footage, and only storytelling.

H2N: It seems like there’s a pretty vibrant documentary scene in Mexico.

EG: Yeah, it’s a great moment in Mexico for docs. The thing is that with the digital revolution we became more independent. And you know, Mexico is a really complex place, and Latin America is a very complex place, so it has a lot of stories. They have a lot of conflicts. We’re always on the edge. And those are the best stories for cinema. Those who are on the edge, no? That’s why I don’t like this heroic vision of docs. Because it’s easy in Latin America. Who is the best filmmaker, the one who shows the worst tragedy or what? It’s not about film. So in Mexico in a way, and in Central America, South America, these stories are really something that we and the whole world absolutely will be connected to. Stories about migration—people who have to leave their families and go to face death in order to make a better life. That’s something that everyone will connect to. Because we have a reality that can be really empathetic with the rest of the world, yeah? And that’s why a lot of doc filmmakers are getting a chance. Because also the places to show are better than 12 years ago, 15 years ago, so now it motivates also the filmmakers. There were times when you knew that your film would never be seen, and that’s not quite motivating for a filmmaker, no? Now it’s a different moment for Mexican cinema, for Latin cinema actually. The same thing is happening with fiction film. They are well-received in Europe, they are well-received in South America, in Asia, and in the USA some of them, so I think we’re in the same train.

H2N: And what’s it like in Mexico—I mean there’s this unbelievable war going on there—so what’s it like to be working in the middle of that?

EG: That’s a crazy thing. It’s a stupid war, and it’s a shame that people here do not realize because actually a lot of people here are the main cause of the Mexican war, yeah? The drug consumption and control is putting us in a lot of problems. “Smoke what you grow,” that’s what we say in Mexico. And also the problem with guns, the freedom of having guns you have is bringing a lot of problems, because we are neighbors. That’s something we can never separate, so it is a common problem right now. But that’s the truth, there’s a feeling that in the U.S. that this thing is happening to us. But it’s the same story with Afghanistan, Iraq. That’s why it shocked, 9/11. Because Americans felt war in their territory, and that’s shocking. Now in Mexico you have to change a lot of things in the daily life. For example, driving in the road, there’s certain hours that you better not be in the road, yeah? There are a few provinces that you better not be in at night, or even daytime. Families in some provinces are really scared. It’s like we’re in the middle of something really peculiar, no? Because we are like the main door for the traffic in South America and consumption in the USA. So we are kind of the natural hole for bringing it, no? So that brings a lot of problems with Central America, because there are a lot of gangs in Central America jumping into Mexico, doing business with the cartels in Mexico in order to bring consumption. Now L.A.—the route of L.A. is really peaceful now. Tijuana and Sinaloa, this area. But the Gulf of Mexico and the drugs that are going to New York, that’s the one they’re fighting now, in Mexico. And if people keep on putting their noses we will keep on putting the dead bodies every day. So that’s the problem now. And what has changed? A lot of things. There are a lot of topics that you cannot talk about—not because you will be repressed by the government. It’s because you will get shot by the narcs. So for example talking openly about narcs and drug-dealing is something that people—for example this conversation in Mexico now has to be quiet. You have to whisper those things. Because you never know if the guy sitting at the next table is related with La Mafia, no? So it’s been changing a lot of the daily life. And in filmmaking the same thing. There are places that you better not use as a location because you will have problems with the cartels. There are topics that you better not speak about because you will be threatened. So a lot of things are changing now in Mexico. We have 150,000 dead bodies in six years! It’s more than the civil war in Central America in 12 years. But the world doesn’t know about it. I don’t know if they don’t know or they don’t care. But it’s the same thing, no? So now the main problem we have is guns in Mexico. And they are all bought in the Walmart or in the Kmart. So my opinion is it’s a crazy and it’s a nonsense war bringing a lot of violence in Mexico, and the only solution is legalization in the rest of the world, something that will never happen. And the problem is that we are forgetting a lot of our problems, because we are always only focused on that thing. The negotiations of migrations between Mexico and the U.S., they are stopped. Now Mexico is not pushing that issue; that is a quite important issue in bilateral politics. It is quiet, because now the problem is the drugs. We are trying to at least sensitize people, in order to at least question this thing about having a gun, or being able to buy a gun in every regular store, yeah? Because I know the family men do it for a reason, but then the thing is the Mafia will always jump into that chance and they will buy the guns. There are cities, important cities, where kids cannot go out at night. Because you never know if there’s gonna be a grenade, if there’s gonna be a car bomb or a shooting, or whatever. It’s corrupting a lot of police officers. So it’s a kind of a cancer. It’s a cancer treated as a flu. Now there is a group of victims crossing the U.S., talking about what’s going on there. It’s called La Caravana de la Paz. And they have been now in L.A., they are visiting Arizona, and they will finish with Obama I hope, in Washington. It’s hard to have a kid now in Mexico, because you’re always thinking about it. Should we move? Should we stay? Should we wait until things get worse? Or will it become better? We’re always guessing. I’m thinking about my American green card, or residency. Something that in 40 years I never thought about. So I hope. I hope. But for example in filmmaking it’s a terrible thing. I’m developing a project that’s about the risks of journalism in Mexico. And it’s something I have to keep quiet. Because now Mexico is the most dangerous country for journalists. Even more than Iraq.

EG: That’s a crazy thing. It’s a stupid war, and it’s a shame that people here do not realize because actually a lot of people here are the main cause of the Mexican war, yeah? The drug consumption and control is putting us in a lot of problems. “Smoke what you grow,” that’s what we say in Mexico. And also the problem with guns, the freedom of having guns you have is bringing a lot of problems, because we are neighbors. That’s something we can never separate, so it is a common problem right now. But that’s the truth, there’s a feeling that in the U.S. that this thing is happening to us. But it’s the same story with Afghanistan, Iraq. That’s why it shocked, 9/11. Because Americans felt war in their territory, and that’s shocking. Now in Mexico you have to change a lot of things in the daily life. For example, driving in the road, there’s certain hours that you better not be in the road, yeah? There are a few provinces that you better not be in at night, or even daytime. Families in some provinces are really scared. It’s like we’re in the middle of something really peculiar, no? Because we are like the main door for the traffic in South America and consumption in the USA. So we are kind of the natural hole for bringing it, no? So that brings a lot of problems with Central America, because there are a lot of gangs in Central America jumping into Mexico, doing business with the cartels in Mexico in order to bring consumption. Now L.A.—the route of L.A. is really peaceful now. Tijuana and Sinaloa, this area. But the Gulf of Mexico and the drugs that are going to New York, that’s the one they’re fighting now, in Mexico. And if people keep on putting their noses we will keep on putting the dead bodies every day. So that’s the problem now. And what has changed? A lot of things. There are a lot of topics that you cannot talk about—not because you will be repressed by the government. It’s because you will get shot by the narcs. So for example talking openly about narcs and drug-dealing is something that people—for example this conversation in Mexico now has to be quiet. You have to whisper those things. Because you never know if the guy sitting at the next table is related with La Mafia, no? So it’s been changing a lot of the daily life. And in filmmaking the same thing. There are places that you better not use as a location because you will have problems with the cartels. There are topics that you better not speak about because you will be threatened. So a lot of things are changing now in Mexico. We have 150,000 dead bodies in six years! It’s more than the civil war in Central America in 12 years. But the world doesn’t know about it. I don’t know if they don’t know or they don’t care. But it’s the same thing, no? So now the main problem we have is guns in Mexico. And they are all bought in the Walmart or in the Kmart. So my opinion is it’s a crazy and it’s a nonsense war bringing a lot of violence in Mexico, and the only solution is legalization in the rest of the world, something that will never happen. And the problem is that we are forgetting a lot of our problems, because we are always only focused on that thing. The negotiations of migrations between Mexico and the U.S., they are stopped. Now Mexico is not pushing that issue; that is a quite important issue in bilateral politics. It is quiet, because now the problem is the drugs. We are trying to at least sensitize people, in order to at least question this thing about having a gun, or being able to buy a gun in every regular store, yeah? Because I know the family men do it for a reason, but then the thing is the Mafia will always jump into that chance and they will buy the guns. There are cities, important cities, where kids cannot go out at night. Because you never know if there’s gonna be a grenade, if there’s gonna be a car bomb or a shooting, or whatever. It’s corrupting a lot of police officers. So it’s a kind of a cancer. It’s a cancer treated as a flu. Now there is a group of victims crossing the U.S., talking about what’s going on there. It’s called La Caravana de la Paz. And they have been now in L.A., they are visiting Arizona, and they will finish with Obama I hope, in Washington. It’s hard to have a kid now in Mexico, because you’re always thinking about it. Should we move? Should we stay? Should we wait until things get worse? Or will it become better? We’re always guessing. I’m thinking about my American green card, or residency. Something that in 40 years I never thought about. So I hope. I hope. But for example in filmmaking it’s a terrible thing. I’m developing a project that’s about the risks of journalism in Mexico. And it’s something I have to keep quiet. Because now Mexico is the most dangerous country for journalists. Even more than Iraq.

H2N: Oh right! At the L.A. Film Festival I saw the film Reportero about that topic. But at the same time, talking about heroes, you see these people who are willing to risk their lives, even in the midst of the worst kind of violence and corruption.

EG: We still have those heroes. But you know something, it’s not easy to change your life. It’s the only way they have to make a living. So it’s something they have to do, also. It’s not heroism, it’s a necessity sometimes. So for example now that’s an issue. It’s amazing—you cannot have a free press in Mexico now. We won the right to have a free press, but we cannot again because all the editors are threatened, all the owners are threatened, but the problem is that the ones who pay are the reporters. The most vulnerable in the chain, yeah? Trying to make for example a film about migration—if you go to the border of Sonora and Arizona that’s a really dangerous place because the cartels are the ones who control that place. So then we are not able sometimes to show that thing. Those are important things to show to the world and for us and for the American people the problems of our border. So it’s changing a lot of lifestyles, Mexican lives. On the other hand—that’s one of the biggest contradictions—life goes on. Beaches are packed, resorts are packed, Mexico City is packed, life is still the same because it’s not like there’s bombs on every corner. But yeah, if I open now for example—if I open one paper in Mexico you will have on the front page four heads that were left I don’t know where. And 20 dead bodies arrived—20! So it’s brutal. Every day that you open a paper in Mexico you will have something like that. Every day. Every day. So it’s really a shocking thing. For example let me show you this—the Internet here is terrible, but, yeah… [EG shows me a long list of violent drug crimes on the main page of a Mexican online newspaper] And it’s any paper. It’s like opening the New York Times. [EG laughs] Just as you read here that Iraq and Syria, or I don’t know—we’re having that gamut at home. It’s terrifying, really terrifying. Sometimes I don’t open the newspaper. For example, something that has changed: I used to listen to the radio news every morning when I was having breakfast with my kid and driving him to school. I don’t do it anymore. We changed that habit. Because I don’t want my kid to go to school every day listening to that violence. Kidnappings, and sicarios [hired killers], murderers, bodies without a head and heads without a body and all those things—I don’t want my kid to go to with that. So now, only the Beatles are on the—it’s a good thing for us. We changed that habit. Family—we do not talk about those things.

EG: We still have those heroes. But you know something, it’s not easy to change your life. It’s the only way they have to make a living. So it’s something they have to do, also. It’s not heroism, it’s a necessity sometimes. So for example now that’s an issue. It’s amazing—you cannot have a free press in Mexico now. We won the right to have a free press, but we cannot again because all the editors are threatened, all the owners are threatened, but the problem is that the ones who pay are the reporters. The most vulnerable in the chain, yeah? Trying to make for example a film about migration—if you go to the border of Sonora and Arizona that’s a really dangerous place because the cartels are the ones who control that place. So then we are not able sometimes to show that thing. Those are important things to show to the world and for us and for the American people the problems of our border. So it’s changing a lot of lifestyles, Mexican lives. On the other hand—that’s one of the biggest contradictions—life goes on. Beaches are packed, resorts are packed, Mexico City is packed, life is still the same because it’s not like there’s bombs on every corner. But yeah, if I open now for example—if I open one paper in Mexico you will have on the front page four heads that were left I don’t know where. And 20 dead bodies arrived—20! So it’s brutal. Every day that you open a paper in Mexico you will have something like that. Every day. Every day. So it’s really a shocking thing. For example let me show you this—the Internet here is terrible, but, yeah… [EG shows me a long list of violent drug crimes on the main page of a Mexican online newspaper] And it’s any paper. It’s like opening the New York Times. [EG laughs] Just as you read here that Iraq and Syria, or I don’t know—we’re having that gamut at home. It’s terrifying, really terrifying. Sometimes I don’t open the newspaper. For example, something that has changed: I used to listen to the radio news every morning when I was having breakfast with my kid and driving him to school. I don’t do it anymore. We changed that habit. Because I don’t want my kid to go to school every day listening to that violence. Kidnappings, and sicarios [hired killers], murderers, bodies without a head and heads without a body and all those things—I don’t want my kid to go to with that. So now, only the Beatles are on the—it’s a good thing for us. We changed that habit. Family—we do not talk about those things.

H2N: So then in the Cuates de Australia I guess they’re too isolated…

EG: It’s not worth it for the narcs—they don’t care about it, there’s no way. They cannot grow marijuana or amapola [poppies], or… they cannot grow those things. It’s isolated, they cannot hide from anyone. And because the town is not in a fight. Because the problem is when the two gangs are fighting for one province or one town. It’s like the old times—it’s amazing, no?

H2N: Yeah, that seems like their greatest freedom. I thought that was interesting too, like when the census worker comes to ask the woman what possessions she has and she’s a little embarrassed but she’s also a little bit laughing at him—like, “we have nothing.”

EG: Exactly. That’s a beautiful thing with them. They have good time for raising the kids. They are with the kids. For example every day at noon we used to ride horses and talk. That’s something you can’t do in society sometimes, just to talk with another guy. They are every day with the kids and with the wife, and with the grandfathers, and it’s a family issue, and so that’s something that’s shot in the film, it’s portrayed in the film. Kids go walking to school and it’s the school where they will meet their future wife, yeah? They know each other since they were kids.

H2N: And they play-act at being adults with girlfriends…

EG: Exactly, trying to be a grown-up. Playing like if they were men. Kids learn how to do stuff very young, no? And you know, because also having a kid has a different meaning for them. For us it’s kind of a beautiful gift and everything. For them it’s a gift but it will be someone who will be able to help the economy of the family.

H2N: I wanted to ask you about the recurring imagery of water throughout the film.

EG: It was the only way of showing the problem with water, because something that I like also is that it is not like I have shot in Rwanda or Sudan, where you see drought and it is kind of genocide. Here it is with the simple things. Because it connects us as people from the cities also. It’s not like having death every moment. Like if I was shooting a drought in Africa—droughts in Africa are really really something terrible. Because they are starvation, and a lot of things, no? Here you see people like you or myself, yeah? Depending on water just like you and myself. So, for the common things, for taking a bath, for drinking. But the only way that I could talk about drought was using the water as a timeline. That’s how we used the water.

H2N: But they also use it for baptism…

EG: Well that’s a beautiful thing. It has a lot of meaning. Baptism is like that. They are sacrificing a cow in order to bring the feast to the people who were invited to the baptism. They are sacrificing a cow not because they are mean. It’s like a very primitive thing, you know? They are sacrificing a cow because there will be a party, in order to talk about baptism, which is related with water, and this cow will be offered to the guests. So it’s a whole idea of sacrifice in between, no? That’s why we listen to the mass while the kids are sacrificing the cow. And then it’s refreshing to see once again water, so in a way that’s a beautiful thing. Water is always refreshing here. Rain! I feel really proud of the film and I was looking at the final cut now with the sound mixing, and after everything when rain came I felt refreshed. Because of the noise and the sounds and everything. And so it was a kind of a cool thing that happened with the film, in my point of view.

H2N: It also feels biblical when the water comes.

EG: Yeah, the whole thing has biblical—it’s an exodus. I don’t know, I was raised Catholic; maybe I am really influenced without knowing with Catholicism and with all the layers of Catholicism. Because it’s not only about going to church, and all those things, no? And praying, and—no, it’s about sacrifice, it’s about hope, it’s about wishes, it’s about a lot of things. Every time I make a film there’s something there. I was infected. [Both laugh]

—Paul Sbrizzi