LYNNE SACHS: FROM THE OUTSIDE IN (A RETROSPECTIVE)

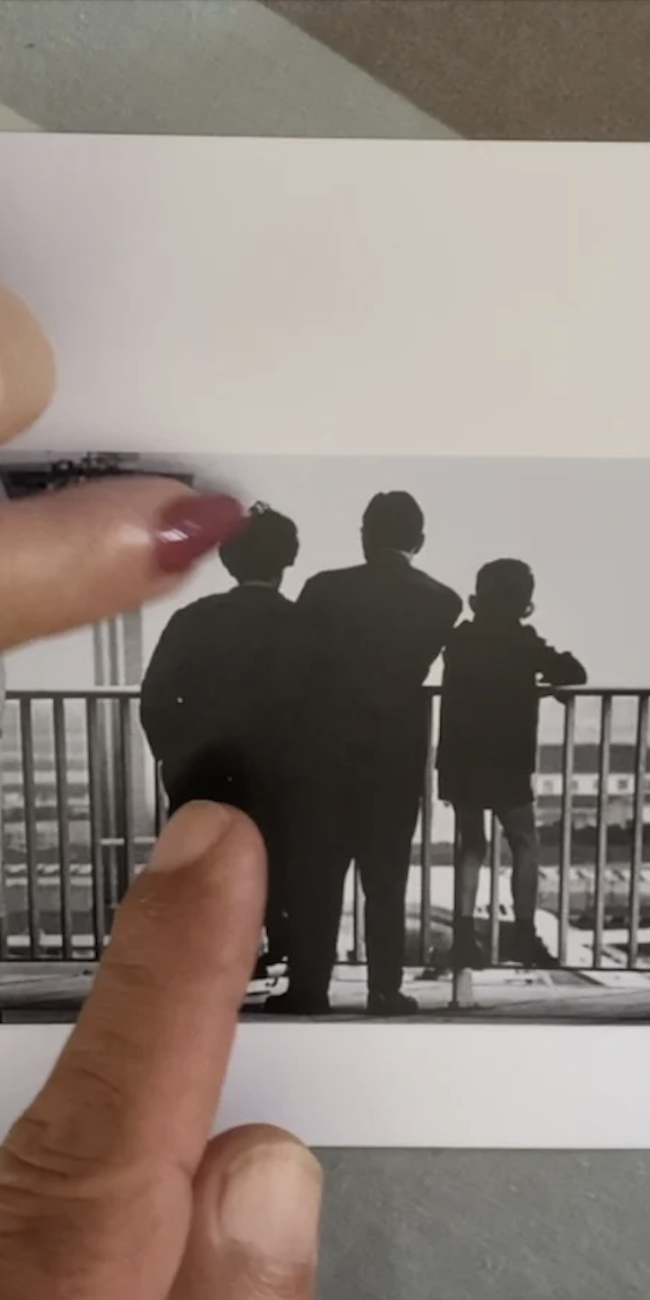

Lynne Sachs’ latest film, Contractions, exists, like much of her work, at the intersection of experimental and documentary film practices. In the 12-minute work, superimposition, narration, and choreography are intermingled–all captured using a graceful and haunting camera language that lends what we see the spirit of poetry. The subject of the film is an abortion clinic in Memphis in the wake of the overturning of Roe vs.Wade by the supreme court in 2022. In Sachs’ film, we see sky and then the unglamorous concrete of the clinic’s parking lot, and eventually, people. The figures we see are shot from behind, and appear to be wearing hospital gowns. They stand staring at the single, freestanding building, surrounding it almost like Romero’s living dead. But these aren’t monsters. Sachs explains, “The women in the film were local activists who had agreed to be in the film without really knowing what they would be doing. I had them for one morning only. To give them more anonymity, I shot them from behind, and that released them from being easily recognized, and, honestly, from feeling super self-consciousness.”

The film necessitated a different approach for Sachs for practical reasons. As she explained, “We were all very worried about security issues in Memphis, since standing in front of a women’s health clinic anywhere in Tennessee can become rather contentious. So having a very tight plan was really critical.” In order to make sure things went smoothly and quickly, Sachs used storyboards for the film, “I storyboarded all of the visuals for Contractions in a way that I usually don’t do,” the filmmaker said, “I had never been to the building where we shot, so I had to imagine it as I drew each image.”

The results Sachs achieves are somber and elegant. The entire film evokes modern dance with its pared down language of bodies in space and simple gesture from both performers and the camera. And while the subject of Sachs’ film—the ongoing attack on women’s rights by the U.S. government—is monumentally important, so is its form. Like her film Investigation of a Flame, which chronicles the history of the Catonsville 9 (a group of nine catholic activists who protested the Vietnam War), Sachs’s documentary integrates the poetic and handmade. Through this, she creates an intimacy with her subject that denies traditional documentary objectivity in favor of a more organic, personal and artistic truth.

Contractions and Investigation of a Flame are just two of the films being screened at Manhattan’s DCTV Firehouse in June as part of “Lynne Sachs: From the Outside In.” The retrospective, running from June 7-11, breaks up Sachs’ work thematically into programs. This novel approach is in large part thanks to DCTV’s Dara Messinger, who Sachs says, “brought her exquisite cinematic sensibility to every program, juxtaposing longer and shorter films in ways that bring out our themes in really inventive ways — from “Bodies and Bonds” to “Flightless” to “It’s a Hell of a Place”, it’s proof of her understanding of cinema as a collective art form.”

Sachs, who is celebrating the 40th anniversary of her association with DCTV, has been making films since the early 1980s. Her work spans a variety of subjects and modes, from purely poetic and experimental work, to personal travelogs and emotionally candid documentaries. Throughout all Sachs’ work, however, the artist’s unseen (and sometimes seen) presence endures.

A still from CONTRACTIONS

Sachs is a part of the films she makes and because of this, there is a unity of vision and consistent personal themes to her corpus, such as family, activism, travel, women, and others. A Film About A Father Who and A Year in Notes, while wildly different in scale and form, both stem from the artist’s life. A Film About a Father Who is Sachs feature-length exploration of her charismatic and mysterious father. The film utilizes an array of formats and footage as well as interviews and newly shot vérité to create an ambitious and moving work of personal documentary.

A Year in Notes and Numbers condenses a year in Sachs life to four minutes through a montage of handwritten notes from daily life, many of them detailing family, health, and work. Despite their marked formal differences, both films clearly bear her authorial stamp–a personal candor and a nimble handling of materials and themes. This is often where Sachs’ films evoke the work of other independent film artists of the past. In her words, “All films are documents of people gathering together to make something. I think of film artists like Hollis Frampton or Michael Snow who recognized in a very astute and invigorating way that they weren’t doing anything more than documenting and then subverting the world as they experienced it. They were refracting reality while witnessing it.”

This understanding of the nexus where documentary and experimental film practices meet might seem obvious but these two cinematic modes have not always interacted. As Sachs notes, “The documentary and experimental communities were not mixing at all until about ten years ago. From the experimental world there was snobbery and from the documentary world there was bewilderment. Now there’s a sense of curiosity and sharing between the two.” Sachs’s work, however, offers a great example of the hybrid approach, one that is being more readily recognized by filmmakers and audiences. A leading exponent of this new trend is Prismatic Ground, a film festival that focuses on experimental documentary. In 2021 the festival bestowed their inaugural Ground Glass Award on Sachs for “outstanding contribution in the field of experimental media.”

Sachs’s fluid practice started early. “I have a long relationship with DCTV, beginning in 1984 when I took my first video class there.” Sachs says, “While a student there, I created an expanded cinema piece with video and dance […] I sort of thought it would be my first documentary, but it really became more about the body, work and viewing, feeling of being an outsider in an unfamiliar place. I created it all there at DCTV.” Now, with this exciting new retrospective, Sachs has returned to DCTV, a 50-year-old community initiative in lower Manhattan that uses filmmaking tools to empower communities, to share her career-long dance with experimentation and documentary with New York audiences.

Sachs’ enthusiasm for her world of films and people is infectious. She understands independent and artist made films as a community organism of sorts, one that needs to be nourished and that thrives on interconnectivity. For her, communication is key, even when her work confronts notions of impossibility. Often her work serves as testament to the creativity and frustration of translation (made explicit in her film The Task of the Translator). Despite these ongoing existential and linguistic struggles, there is an ineffable hope that permeates her films. With each new work there is the possibility of communication–the communication of a life lived, of a vision, of a time on earth captured in new and unique ways by a singular artist.