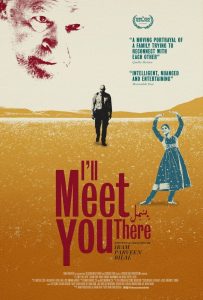

From Cancelled SXSW Premiere to Virtual Distribution: Iram Parveen Bilal on “I’ll Meet You There”

I had the pleasure of watching and reviewing Iram Parveen Bilal’s I’ll Meet You There out of SXSW 2020. Unfortunately for all involved, that festival was cancelled because of the then-new Covid-19 pandemic. Since these were early days, yet, there were no plans in place to screen the films that would have premiered, though some would later stream on Amazon. Bilal’s movie tells the touching tale of Pakistani Muslim immigrants struggling to adapt to American life without losing their culture and faith. Since the aborted festival run, Bilal and her team have worked hard to find the best way to launch the film. Today, February 3, marks the start of their distribution plan, via Abigail Disney’s Level Forward. Back at the end of 2020, I spoke with Bilal about how she got here. What follows is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: Let’s start with the inspiration for making I’ll Meet You There. What drew you to this particular subject and this particular treatment of it?

Iram Parveen Bilal: The film was born back in film school. This was a few years after 9/11. I was on the West Coast and since I was a woman, the severity of the patriot act on me was less. I feel like males on the East Coast especially who were in their late teens were being profiled in a different way but even on the West Coast, I still knew people who were being affected by the so-called Patriot Act. I remember at Caltech, I had a friend, an Iranian friend, whose dad was picked up after morning prayers from the mosque and the only charges against him were that he had incorrectly filed his tax returns. So these things were happening. And at that point I was an engineer. I was not a filmmaker.

And so I graduate and go to film school. And in film school, the first writing class I had, I just had this idea that I wanted to … I had been at a Muslim community event, and I saw this very orthodox-looking Muslim, but in a police uniform. And I just immediately went, “Oh, my God, what an interesting life this guy is following, he’s probably living in all this sort of gray-area kind of conflict and probably can’t express much, and it’s like, where do your loyalties lie?” That was the time, sadly, when Muslim equaled terrorists for most people in America.

And even Muslims found themselves kind of defending or always being in this “guilty until proven innocent” sort of mindset, because you were just conscious about people the moment the name of your religion came up, but it was just … it’s very different now. Today it’s very different, but that was the time. So that image just never left my mind. And as I was writing the script, another thing that was very personal to me was that I grew up loving to dance.That was my first passion, but I grew up in a Muslim culture in a middle-class family where I felt that art was relegated to the elites in Pakistan.

And so I didn’t have access to that. And so the idea and the notion of being a professional dancer was absolutely “no.” I mean, film was probably still pretty rebellious, but my parents were very supportive, frankly. But I think dance is such a taboo in my culture. As kids it would not be uncommon to hear that dancers come from the red-light area, which was the brothels in a small area outside of Lahore. So there was this big taboo and there were all these multiple standards: you would go to a family party and your uncles would be clenching VHS tapes of Bollywood songs where everybody’s enjoying this Bollywood dancer dancing, but yet if your daughter said that she wants to become that, that was absolutely not okay.

And so I didn’t have access to that. And so the idea and the notion of being a professional dancer was absolutely “no.” I mean, film was probably still pretty rebellious, but my parents were very supportive, frankly. But I think dance is such a taboo in my culture. As kids it would not be uncommon to hear that dancers come from the red-light area, which was the brothels in a small area outside of Lahore. So there was this big taboo and there were all these multiple standards: you would go to a family party and your uncles would be clenching VHS tapes of Bollywood songs where everybody’s enjoying this Bollywood dancer dancing, but yet if your daughter said that she wants to become that, that was absolutely not okay.

So when I was between undergrad and grad, I traveled under the Watson Fellowship and I studied dance in different cultures as a way to prove that there’s nothing taboo about something that’s so native … that rhythm and beats are native. In fact, I backpacked around India as a Pakistani, I was 21. Traveled to Kenya and studied that dance was used for tribal communication, traveled to Ireland and studied square dancing in Ireland. These were two different elements and I started writing the script and that’s kind of how it happened.

And then it was very personal because my sister, who taught me how to dance, had a sort of rebirth, and this is all connected in some way, because before 9/11 you were just Muslim and nobody cared. After 9/11, then there was, “Okay, well, what kind of Muslim are you?” And suddenly you go, “Okay, well, where do I fall on the spectrum of being Muslim?” So in some ways the Protestant movement in Islam, as well as born-againism, started. You needed to sort of say, “This is the sort of Muslim I am.”

So, in my family, for example, where you would have co-ed wedding banquets, where people would dance together, you now had to write on the wedding card when the dancing would happen, so the conservative members would leave the wedding after dinner so people could dance. We are three sisters, and my oldest sister is the one who taught me how to dance, and I’m not saying classical dance, just Bollywood dancing. She now thinks dancing and music are no necessarily the Islamic way. She’s seen the movie. She thought it was very “mature.” So in some ways I think that the conversations between my movie’s characters Baba and Dua are things that I would have loved to really sit down and talk to my sister about.

And the whole political angle of it has come from just being an immigrant in America after 9/11 and just seeing what communities are facing. For a really long time, people would say that that doesn’t happen or, “Oh, come on, the FBI wouldn’t do that.” Even in the making of this movie, and by some of my mentors, I have been questioned, “Well, this sounds a little … this just sounds unreal.” And I would have to go, “Well, I know people who have faced this.” And now we have documentaries like The Feeling of Being Watched, that show that there has, in fact, been surveillance, and you have all these court cases.

In some weird way, maybe this is a really good time for the film to come out because we can have all that proof and be, “It’s not just me trying to paint and demonize law enforcement.” There has been a lot of profiling. So, it was the external socio-political element plus the internal striving to dance. These two melded themselves into one movie.

HtN: So you were all set to premiere this at SXSW. How did the festival’s cancellation affect the rollout that you had developed for the movie?

IPB: Of course, it affected us hugely. I mean, first and foremost, we had a spectacular press junket. We were going to be sold out, you know how it is, it’s all about the buzz and the perception. And so our hope was that we would be able to create enough buzz and perception to then get some offers. And what happened is, obviously, the moment this happened, there was so much uncertainty. And the first thing people do when there’s uncertainty is hold on to what they have. And that translated, as far as distributors go, to them just not purchasing anything. And there was this notion that everybody had that, “Oh, okay, well, the pipelines are disrupted and nobody’s shooting, so everybody’s just trying to gobble stuff up.” And I actually thought that was a myth because we were talking to sales agents and that wasn’t the case. Distributors purses were sealed in the immediate aftermath. Everyone was waiting and seeing. This is all unprecedented.

Nikita Tewani as Dua in I’LL MEET YOU THERE

The beauty of the cancellation of SXSW, one of the silver linings, was that a lot of competition filmmakers bonded together. And we would talk to each other and be like, “What are you getting? What are you hearing?” And what happened is that when everything shut down, all the big dogs who had their film releases also shut down, were now also going to be streaming. And by the way, streamers have stopped picking films up in the last two years from festivals. Netflix has hardly bought anything from a festival in the last year, even before the pandemic.

HtN: Right, because often a film goes into a festival having already been picked up by Netflix.

IPB: Basically, what is going on is that they’re trying to really rev up their Netflix Originals arm. So either they’re doing in-house production or they want to be on board with your film way before it’s gone. And we tried. At every stage, we tried. This is something that’s very personal because I feel that the system does this with films by people of color and films that come from an unseen niche. What they do is from the beginning, people don’t fund it, saying, “Oh, it’s too small,” or, “Get us an actor who is bankable,” which never happens because it’s a Catch-22. So they don’t fund them. Then you go off and figure out a way to make it for a lot less money. Then they tell you, “Oh, it’s too small for us to distribute.” So you think, “Well, if you gave us money, it wouldn’t be that small in the first place.”

We’re actually glad we had PR and Sales to deal with when all the freezing happened post SXSW. A few people stopped their PR, but our PR smartly said, “Listen, there’s a sliver of a window. People have this pity for SXSW, and they’re still all revved up to watch. Let’s just go get the reviews.” And I’m actually glad we did, because I was also of the mindset that we don’t know. We don’t know what tomorrow is going to be. When the world unpauses, people aren’t going to go, “SXSW, where is SXSW?,” People would have moved on.

Anyway, long story short, we reached out to everybody and I think it was a mistake to reach out at that point, because people were just … we got a few offers, but they were not what we wanted in terms of a lot of upfront commitment. And so we said, “Okay, let’s pause and reach out again in the fall,” with this notion that the pipeline disruption will become a little more severe for these streamers, but these guys have two things. They work way ahead in terms of content. So they have a year, if we were … If production stopped for a year, then maybe in a year you could approach them. Secondly, as I said, all the bigger films were now coming down and pushing us out. So where they would normally say, “Oh, we love the film, but maybe we license it,” which essentially means that they will buy it for 10%, 5 to 10% of what they would offer you if they were to buy the film. And this is what I’ve been hearing and from other friends and other peers as well.

Iram Parveen Bilal on set of I’LL MEET YOU THERE. Photo by Alia Azamat.

It got to a point where we were like, “Okay, fine, we’ll go back.” We went back to the initial offers we got after we reached out to everybody, and essentially the beautiful thing that happened is, in this entire sort of navigation, I decided to just be patient. I thought, “We’ll wait.” And so finally, Adrienne Becker, one of the producers of some of the other SXSW films – she produced Topside and she also produced Holler – was with me in a few panels and I believe we connected on the activist level and she seemed impressed to see how I was handling the uncertainty. And then she finally saw the movie and she came back and said, “I love this film and if there’s any way we can help, let me know.” .

We won the Women in Film finishing fund. And what I usually do with my films is I travel around the country and build up these big screening events that are at a higher price point. And you have a red carpet, you see the movie and you have a great panel. And so we started thinking and Level Forward said, “We’ve been doing these live digital events.” So, then we had to go back to our original distributor who is giving us a VOD release on the 12th of February. And then the week leading up to that, we’re going to have these 5 live digital events, starting on February 3, arranged by Level Forward. Those will be done as separate events that you can discover online.

In some ways we have just tried to figure out what is the best, what is the closest we can get to me traveling and doing this in a virtual setting. We’re trying to hit as high as we can and just create a buzz, because I saw what IFC did with Shithouse, which won the SXSW Jury Award, and it was not even a blip in the noisy climate of film distribution and it just came and went. We are being very targeted and strategic. I’m using my network and then we’re partnering with a variety of organizations that leverage the themes of the film and are creating impact. So we’ll see. I mean, it’s a giant experiment, but I’m hopeful.

HtN: Well, I think that’s a pretty fascinating journey all the way up to distribution. It’s not over yet. I look forward to seeing what happens with it and it should be an interesting model that perhaps others could emulate.

IPB: I hope so. I would love that. I think Adrienne’s team is so incredibly cutting edge. Thank you so much!

I’ll Meet You There begins its digital rollout on Wednesday, February 3, via Level Forward. Complete information on the special live screenings leading up to the official February 11 premiere can be found here, with short descriptions below:

Feb 3: Race and Surveillance

Feb 4: Rhythms of Pakistan

Feb 5: Immigrants & Identity

Feb 6: Filmmaker’s Workshop–Guarding the Frame

Feb 11: Premiere Gala with Cast & Creative Team

And then, on February 12, via Freestyle Digital Media, the film releases on VOD all over North America.