(The Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) puts together some of the most intriguing and fun cinematic retrospectives in the world and this month’s “The Vertigo Effect” is no different. Featuring films that realte to Hitchcock’s brilliant themes of memory, obsession and death in Vertigo, there’s quite a wide swath to choose from. If you’re in the area, you have until the end of April to check it out.)

If you look around you hard enough, it is not difficult to place yourself directly within the realm of experience endured by Jimmy Stewart’s Scotty Ferguson in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo. Living in New York one’s everyday experience is riddled with bursts of happenstance, fate, and doom. At any time, with a toss of a coin, it is not uncommon to see faces you could have sworn you’ve seen before— if not yesterday, or in the past, perhaps even just that day. It is easy to imagine evidence that the world is following you, like any one of the millions of cameras that surveil so many could be directed not solely at you, but at your secrets as well, your fears, your fragile destiny preyed upon like some orchestrated ruse of reality, or better yet, conspiracy, the glitches— incidents repeating, characters and faces recurring— become visible for the first time. It’s like being a character in your own movie.

BAM Cinematek’s “Vertigo Effect” series invites the viewer to see how the evolution of the oneiric, a man possessed narrative form, truly gained its traction. Named for the remarkable innovation in cinematography (Robert Burks, who shot almost everything Hitchcock did between Strangers on a Train to Marnie, has to hand it to 2nd Unit Camera Op Irmin Roberts here, who deserves the distinction of pioneering the technique, if not inventing it), now iconic and heavily quoted, the films included in the series run the gamut of bewildering dreams, questionable memories, false identity, secret plots, and murder. From the schlock (Basic Instinct, Mulholland Drive) to the interstitial (Sans Soleil), it’s easy to see how this one replaced Citizen Kane at the top of the heap a few years back.

It is a certain human phenomena to see one’s reflection in another’s eyes. It is even more common to see in the other’s eyes a reflection of yet another, familiar, kindred spirit. Herein lies the curse, as Pasolini would put it, of the conflict between “A, and B.” (Petrolio). To see someone’s double, to see one’s own self that is, has been colloquially known as a curse resulting in sudden death, where two parallel selves not meant to collide do in fact, and that collision is terminal, fatal, and head-on. Think blindness from any mirror. But for the veridical (in oneirology, a dream that has predictive quality), the journey that is so often at the heart of the subjective, first-person suspense narrative in film, there would be little wonder to behold at life’s accidents, the ghosts of chance, the twists and turns our destinies travel.

Of the selection, certain landmarks stand out. La sirène du Mississipi (Mississippi Mermaid), all the other auteur legendaire platitudes not withstanding, is Truffaut’s most honest work in genre, and one I have been particularly obsessed with since I first saw it, some late snowy night upstate on an rabbit-eared TV set, on WNET no less, and was drawn to it immediately. Set on the island of Reunion, the picture follows Jean-Paul Belmondo’s Louis as he awaits the arrival of his mail-order-bride, Catherine Denueve’s Julie, who appears different in person than her picture right away. The doubts and questions begin there— surely, she must be hiding something– and don’t let up until Louis is left in near ruin from the damage this “Julie” has wrought upon his family cigarette factory and fortune. From there, like a man possessed, he sets off across the world to find Julie, now Marianne, and finds himself upon catching up with her a man still possessed— this obsession he held for finding this person, seeing her again, has turned to love. He cannot bear to turn her in. Instead, he runs with her. For years, I searched for this movie, after that midnight winter viewing, in vain, having tuned in after the opening credits, missing the title altogether, begging people who should have known, what was that film where they wander into the snow together? Where she gives him the poison and he says to her, in one of the most heartbreaking scenes committed to the cinematic record, “Fill it all the way up.” It took a long time plodding through no shortage of French action pictures spread across Belmondo’s filmography for me to figure out its name, that Truffaut directed it, and that it does exist, that I didn’t dream it after all. Let this be clear: don’t miss this one. For the ages.

That Hitchcock’s film has had such a lasting relevance and reverberation throughout the echo chamber of recurrent themes in cinema should come as no surprise. In the director’s own canon, Vertigo stands out. It is truly Hitchcock’s first and only metaphysical suspense, and sets the stage for an ethereal, esoteric realm in noir, where ghosts exist and do linger in the shadows, where revenant threats surround at dark corners. Last Embrace, Jonathan Demme’s tip of the hat from 1979, is designed around the mysterious Jewish human trafficking cult Zwi Migdal (very real, and worth a look if you’ve never read about this subject), and its members’ descendants being mysteriously wiped out by one of the victims’ vengeful, cursed offspring. Roy Scheider, who really hits it out of the park here (Last Embrace and Sorcerer should really be shown in double feature mode more often), crawls through the trauma of losing his wife and his own sanity to a botched espionage mission, only to emerge with this answer that someone has a list, and he’s on it.

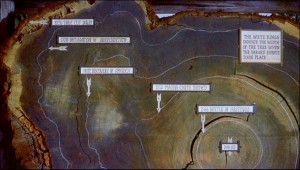

It takes some digging to come up with any answers. It is this introduction of ancient texts, like the Muir Woods museum cross-section of a tree consulted in Vertigo, like the historian’s explanation of who exactly Carlotta was to a bewildered Scottie Ferguson, that allows us to permit and indulge even the furthest stretch of our suspended disbelief, because for all we know, if these ghosts are real, if people can reappear in the form of others, even after they’re dead, it must be because there are secrets in the past we’ve yet to uncover. A dusty book, an old painting in a museum, mysterious Hebrew markings— these are the archaic signifiers of oneiromancy, just as Jung, the study of divination through dreaming’s progenitor, weighed these symbols and their importance in terms of our relation to the unconscious world. The world where memory and imagination meet and intertwine, till one is unrecognizable from the other, creating “interobjects”in place of affirmative absolutes, and obstacles of illusion obstructing the view of the real.

That the series itself is so broad-minded in its worldview of Vertigo’s cumulative effect on any picture with a mysterious blonde, a man plagued by the past, and an imminent, perilous conclusion on the horizon can explain for such a wide swathe of pictures. Larry Cohen’s comment on the movie business at large, the criminally overlooked Special Effects, is a standout, and hard to come by normally. Zoe Lund (nee Tamerlis) of Bad Lieutenant fame (she wrote the script and injects Keitel in the film’s most naked, naturalist sequence) appears in two roles, of the young actress slain by a crazed, psychopathic auteur (Eric Bogosian in rare form!) and as the “non-pro” discovered and cast as her in a biopic of her life directed by same said psychopathic filmmaker, who for some reason, is super fucking rich (a la Schnabel, he lives in a castle on the westside) and also hitting rock bottom (possibly explaining for the taste for murder, or perhaps vice-versa). The implausibility not withstanding, it is really difficult to avoid laughing when everyone, and I mean EVERYONE in New York appears to know exactly who this guy is, and how much his most recent fiasco bombed for, and how he just got pulled off another high-profile production and will never get hired again. I mean, even the Homicide detectives have a joke about how you can probably find him on the unemployment line. I remind everyone in the audience this is a filmmaker we’re talking about. A filmmaker. Don’t miss this one either, if only for how far Hitchcock’s original themes could be stretched.

From Lucio Fulci’s only American production, the excellent Una Sull’altra (Perversion Story, 1969), to Brian De Palma’s Paul Schrader scripted Obsession, not a single stone of the absurd goes unturned. But there is something gripping in the experience of watching a man plagued by some mystery, a mystery of which, at very least, we know more than he, that keeps us going. Perhaps we’d like to think ourselves smarter, less culpable to treachery, to the plots and plans of saboteurs, than our man here. Perhaps we’re all imagining our own death, our own chase, our own escape. Or perhaps this thing we think we remember, that might have been a dream, was in fact a foretelling, a mirage of the future, revealed to us as children, only now realized too late as it occurs in real time. Chris Marker (whose seminal La Jetee and Sans Soleil— perhaps the most ripe with Vertigo’s effect, barring High Anxiety— are both included in the program) found in Hitchcock’s source material a world of myriad possibilities, and still unanswered questions. Could the future be programmed to repeat itself as dream and memory’s confusion until it is current, until we experience it in present tense? Terry Gilliam, who received the 12 Monkeys project on the strength of Marker’s original texts, seems to have found the answer, and his remake of Marker’s photo roman (image novel), is among the most inspired selections on the slate.

In what amounts to the penultimate moment in Cole’s (Bruce Willis) journey to realizing his own purpose in the course of the future’s taken shape, he hides out in a movie house, sitting with his doctor, Kathryn (Madeleine Stowe) now turned his accomplice on the run. On the screen, plays Vertigo. Jimmy Stewart points to the rings of age on the tree chart, and Kim Novak’s finger traces where in the timeline she, or the mythical spirit spouse of Carlotta, was born and died, all chronologically askew. She speaks to the tree: “Here I was born, there I died, and it was only a moment for you. You took no notice.” Cole is entranced, saying to Kathryn, “I’ve seen this before, when I was a kid, on TV.” We understand him. We understand the feeling. Jimmy Stewart asks Kim Novak, “Have you been here before?” She answers: “Yes.” “When?” he pleads. “When were you born Madeleine, tell me!” Cole shudders. We feel the chill creep up our spines too. “This is just like what’s happening with us,” he says to Kathryn, as she prepares their disguises. “Like the past.” She attempts to glue a false mustache to his face. “The movie never changes. It can’t change. But every time you see it, it seems different. Because you’re different. You see different things.”

In what amounts to the penultimate moment in Cole’s (Bruce Willis) journey to realizing his own purpose in the course of the future’s taken shape, he hides out in a movie house, sitting with his doctor, Kathryn (Madeleine Stowe) now turned his accomplice on the run. On the screen, plays Vertigo. Jimmy Stewart points to the rings of age on the tree chart, and Kim Novak’s finger traces where in the timeline she, or the mythical spirit spouse of Carlotta, was born and died, all chronologically askew. She speaks to the tree: “Here I was born, there I died, and it was only a moment for you. You took no notice.” Cole is entranced, saying to Kathryn, “I’ve seen this before, when I was a kid, on TV.” We understand him. We understand the feeling. Jimmy Stewart asks Kim Novak, “Have you been here before?” She answers: “Yes.” “When?” he pleads. “When were you born Madeleine, tell me!” Cole shudders. We feel the chill creep up our spines too. “This is just like what’s happening with us,” he says to Kathryn, as she prepares their disguises. “Like the past.” She attempts to glue a false mustache to his face. “The movie never changes. It can’t change. But every time you see it, it seems different. Because you’re different. You see different things.”

– Evan Louison