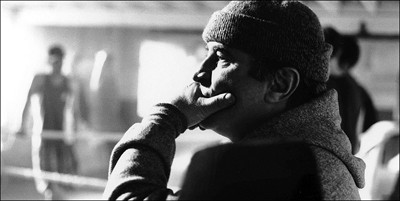

Remembering Bob Hoskins… “A Man So Quick, He’s Even Fast Asleep”

There was something about him. Pugnacious. His voice like gravel. But something in his skin, so tangible and physical that it made you feel like you could reach through the screen and touch it if you wanted to.

I first saw Bob Hoskins onscreen in the movie Mermaids. I had a VHS of it that my family had gotten secondhand. Don’t ask me why, but we had that, and Beaches. For some reason, my mother bought these things. I don’t know if anyone in the house ever watched them. But I did. Repeatedly.

Mermaids is kind of incredible in a way that most things of that time are: lascivious content, oversexed middle-aged women, and Winona Ryder. But Hoskins, in a movie that celebrates camp—Ms. Ryder has an ongoing interior dialogue with God in an extremely Catholic sense, while Cher as her mother reminds her “Charlotte, we’re Jewish,” and Cher literally says the line “I get pregnant if I hang my clothes next to a man’s suit”—somehow manages to bring this smiling workingman gait into every scene we’re privileged to have him in. In a film where he plays a shoe salesman (in his first scene he emerges from behind the stacks and promptly attends to two nuns trying on flats, while Winona Ryder looks on in awe) he is genuine and interesting in a way that most would be reticent to describe such a person. Every single detail of his behavior is so natural, you actually believe he’s a Jewish guy from South Dakota. The way he puts the phonograph on and spins round in one motion once the nuns are gone, the way he ever-so-nonchalantly kicks the ride-on-horsey to get it started for the youngest daughter, the way he watches them go, walking down the Eastport street away from his store, for what seems like forever, before turning and grinning conspiratorially, mischievously to himself before going back inside. You are immediately on the guy’s side. There is just no mistaking it.

Mermaids is kind of incredible in a way that most things of that time are: lascivious content, oversexed middle-aged women, and Winona Ryder. But Hoskins, in a movie that celebrates camp—Ms. Ryder has an ongoing interior dialogue with God in an extremely Catholic sense, while Cher as her mother reminds her “Charlotte, we’re Jewish,” and Cher literally says the line “I get pregnant if I hang my clothes next to a man’s suit”—somehow manages to bring this smiling workingman gait into every scene we’re privileged to have him in. In a film where he plays a shoe salesman (in his first scene he emerges from behind the stacks and promptly attends to two nuns trying on flats, while Winona Ryder looks on in awe) he is genuine and interesting in a way that most would be reticent to describe such a person. Every single detail of his behavior is so natural, you actually believe he’s a Jewish guy from South Dakota. The way he puts the phonograph on and spins round in one motion once the nuns are gone, the way he ever-so-nonchalantly kicks the ride-on-horsey to get it started for the youngest daughter, the way he watches them go, walking down the Eastport street away from his store, for what seems like forever, before turning and grinning conspiratorially, mischievously to himself before going back inside. You are immediately on the guy’s side. There is just no mistaking it.

This is something that Hoskins brought to every role I ever saw him in. There are many signifiers in his body of work—people are at no loss to endlessly discuss the masterpiece perfection of The Long Good Friday, but what about when Hoskins shone brightly in a sea of shit? Isn’t that something more luminous and worthy of praise than standing tall as an oak at five foot six and a half in a perfectly crafted masterwork? What about his role as Father Da Costa in Mike Hodges’ A Prayer for the Dying? Nevermind the more ridiculous aspects of the film, be they the fantastic ending with Mickey Rourke ‘s IRA assassin Martin Fallon hanging from the rafters of the church, or the ridiculous Sammi Davis performance as Da Costa’s blind niece—again, Hoskins shines. His rage as Father Da Costa, silenced as a witness to Fallon’s murder in the churchyard cemetery by Fallon’s subsequent entry to the confessional, is mute, nostril, and foreboding. It is a repressed quality that reeks of a past, tainted. His is the only violence in the film that for even a moment appears to be undeniably of the real (which, interestingly enough, was disowned by both Hodges and Rourke due to supposed editing interference on the part of The Samuel Goldwyn Company).

When I mentioned to a friend of mine a few years ago that I was writing something inspired by the dynamic between Hoskins and Cathy Tyson (where did she go?) in Mona Lisa, after just having seen it for the first time, he sort of laughed, as if to imply that it wasn’t a film that stood the test of time particularly well. This is someone whose opinion I never take for granted even if I disagree with it, as he’s made a number of films I revered before I even met and worked with him, and most likely saw a great many films that have meant something to me in their original context. So I watched it again. And again. And again. And it might be my favorite thing Bob Hoskins ever made. Just how he managed to portray such grace in a befuddled, frustrated, unworldly character, I still can’t, for the life of me, name. The film, of which much has been written and said, follows the unlikely union of two seemingly lost and wandering souls in the underworld of London, both searching for something lost. For Hoskins’ George, it is a return to the stature and position he once held in the criminal element before taking a turn inside, and to regain some sense of humanity and purpose through connecting with his daughter, whom his ex-wife has forbidden him to see. For Tyson’s Simone, a beautiful, mysterious escort, it is a friend from her troubled past, abused and damaged by the denizens of the red-light district.

When I mentioned to a friend of mine a few years ago that I was writing something inspired by the dynamic between Hoskins and Cathy Tyson (where did she go?) in Mona Lisa, after just having seen it for the first time, he sort of laughed, as if to imply that it wasn’t a film that stood the test of time particularly well. This is someone whose opinion I never take for granted even if I disagree with it, as he’s made a number of films I revered before I even met and worked with him, and most likely saw a great many films that have meant something to me in their original context. So I watched it again. And again. And again. And it might be my favorite thing Bob Hoskins ever made. Just how he managed to portray such grace in a befuddled, frustrated, unworldly character, I still can’t, for the life of me, name. The film, of which much has been written and said, follows the unlikely union of two seemingly lost and wandering souls in the underworld of London, both searching for something lost. For Hoskins’ George, it is a return to the stature and position he once held in the criminal element before taking a turn inside, and to regain some sense of humanity and purpose through connecting with his daughter, whom his ex-wife has forbidden him to see. For Tyson’s Simone, a beautiful, mysterious escort, it is a friend from her troubled past, abused and damaged by the denizens of the red-light district.

George is employed by Denny—a for once very frightening and not at all annoying Michael Caine—as Simone’s driver, with the surreptitious assignment of gathering information on one of her clients. In the process, the two become somewhat interdependent and, in turn, inseparable. Simone is at first disgusted by George’s garish lack of wit, ignorance of culture, and generally conspicuous qualities that cause him to stand out like a sore thumb, most especially when he tries to appear one of the more refined and crowded circles within which she operates. George rejects the assignment at first, seemingly disgusted at times by Simone’s ability to sell her flesh and seem so nonplussed by the risk and stigma of the vocation simultaneously. But there is a tenderness, a protective air that develops between them, unlike anything I’ve seen, and I feel as if I must admit here, I have seen a great many of these types of films, be they hooker with a heart of gold meets knight in shining armor types or those of the oddest couple since the last odd couple persuasion.

The main difference at play here, the one thing that seems to drive Mona Lisa to a separate destination from the rest of this trope, is that never between them does the tenderness and gentle affection between them hint at anything more than empathy. It never borders on romance, or even subtly alludes to anything lurid or base. It holds itself back from such temptations, contained in innocuous loving concern, and is thus powerful to watch. There is a scene about two-thirds of the way through the picture, in which George finds himself busting into the ritzy Wellington Suite at Simone’s workplace of choice, convinced of some trouble. Little do his suspicions fail him, but there he finds Simone, bound and gagged. After pouncing on the John, who repeatedly admonishes Simone, tied to the bed, “And I thought you were respectable!,” he turns to remove her muzzle and free her from her bonds. She immediately reprimands him: “George! What is wrong with you? Get out!” The John flees, and George and Simone sit on the bed, together, facing opposite directions. The silence is deafening. It is in this moment where you can see a man, so blinded by emotion and his upbringing, so backwards in his thought, that he can be one with the most salacious elements of a society, in the thick of them even, and still be completely bewildered as to their meaning. And for all of this meaning, all of this humility and shame, Hoskins does but one thing to show us his heart: he hangs his head and sighs heavily, his barreled chest heaving between his broad shoulders. It is a moment of truly quiet compassion, where both characters are too taken by their vulnerability to face each other, and yet their silence says everything, that though of completely different worlds, they can understand in each and the other there is something deserved and begging of forgiveness.

The main difference at play here, the one thing that seems to drive Mona Lisa to a separate destination from the rest of this trope, is that never between them does the tenderness and gentle affection between them hint at anything more than empathy. It never borders on romance, or even subtly alludes to anything lurid or base. It holds itself back from such temptations, contained in innocuous loving concern, and is thus powerful to watch. There is a scene about two-thirds of the way through the picture, in which George finds himself busting into the ritzy Wellington Suite at Simone’s workplace of choice, convinced of some trouble. Little do his suspicions fail him, but there he finds Simone, bound and gagged. After pouncing on the John, who repeatedly admonishes Simone, tied to the bed, “And I thought you were respectable!,” he turns to remove her muzzle and free her from her bonds. She immediately reprimands him: “George! What is wrong with you? Get out!” The John flees, and George and Simone sit on the bed, together, facing opposite directions. The silence is deafening. It is in this moment where you can see a man, so blinded by emotion and his upbringing, so backwards in his thought, that he can be one with the most salacious elements of a society, in the thick of them even, and still be completely bewildered as to their meaning. And for all of this meaning, all of this humility and shame, Hoskins does but one thing to show us his heart: he hangs his head and sighs heavily, his barreled chest heaving between his broad shoulders. It is a moment of truly quiet compassion, where both characters are too taken by their vulnerability to face each other, and yet their silence says everything, that though of completely different worlds, they can understand in each and the other there is something deserved and begging of forgiveness.

Hoskins dealt with violence in many of his performances. I’ll never forget seeing a tiny screening of Abel Ferrara’s Go-Go Tales at the now defunct Cinema Nolita on Mulberry St, about five years ago. Afterwards, Abel cycled through, bottle of beer tucked inside his jean jacket. He told me a story about how during the shooting of one scene in the film, which chronicles the last days of a Chelsea strip club, where an irate club-goer realizes his wife is actually one of the club’s dancers and throws a fit, only to be tackled en masse by the club’s security, things didn’t go exactly as planned. Shooting at the fabled Cinecitta in Rome, they employed a legitimate, fairly well-regarded Italian actor for the part of the husband. Hoskins was cast as the club manager (played by Willem Dafoe)’s right hand man. The scene as written was intended to be funny, even by some standards (certainly Abel’s) tame. And as it is depicted in the picture, it is anything but. In Abel’s words: “Soon as I yell ‘Action,’ Hoskins, comes flying over the bar, and everybody on set is on top of this guy, and I’m thinking, ‘We’re gonna kill him.’ So I yell ‘Cut, cut, cut! Guys, ya know, this is a comedy!’ And Hoskins turns to me and says, ‘Sorry mate, but sometimes I just really gotta slug a bloke.’ There’s something in the humor of such an apocryphal tale that I can understand—this was someone who, by all accounts, deplored violence, but was well-versed in the rough and tumble world of working class England. This was someone who knew where he came from and even in the slightest, meekest of roles, had a brood of darkness hidden beneath his mask. Someone who could spell it out for you and didn’t have to.

Hoskins dealt with violence in many of his performances. I’ll never forget seeing a tiny screening of Abel Ferrara’s Go-Go Tales at the now defunct Cinema Nolita on Mulberry St, about five years ago. Afterwards, Abel cycled through, bottle of beer tucked inside his jean jacket. He told me a story about how during the shooting of one scene in the film, which chronicles the last days of a Chelsea strip club, where an irate club-goer realizes his wife is actually one of the club’s dancers and throws a fit, only to be tackled en masse by the club’s security, things didn’t go exactly as planned. Shooting at the fabled Cinecitta in Rome, they employed a legitimate, fairly well-regarded Italian actor for the part of the husband. Hoskins was cast as the club manager (played by Willem Dafoe)’s right hand man. The scene as written was intended to be funny, even by some standards (certainly Abel’s) tame. And as it is depicted in the picture, it is anything but. In Abel’s words: “Soon as I yell ‘Action,’ Hoskins, comes flying over the bar, and everybody on set is on top of this guy, and I’m thinking, ‘We’re gonna kill him.’ So I yell ‘Cut, cut, cut! Guys, ya know, this is a comedy!’ And Hoskins turns to me and says, ‘Sorry mate, but sometimes I just really gotta slug a bloke.’ There’s something in the humor of such an apocryphal tale that I can understand—this was someone who, by all accounts, deplored violence, but was well-versed in the rough and tumble world of working class England. This was someone who knew where he came from and even in the slightest, meekest of roles, had a brood of darkness hidden beneath his mask. Someone who could spell it out for you and didn’t have to.

In Shane Meadows’ sophomore outing Twenty Four Seven, Hoskins plays a man named Alan Darcy, committed to helping the wayward youth of his crumbling, decrepit factory community to regain their sense of self and purpose, through the auspices of a boxing club revival, one which he credits with providing himself and others like him with a similar impetus to change his ways as an adolescent. The teens are surly, far from kind to each other, and, to be blunt, brutal in a particularly British way, reserving no charity or restraint for themselves or the world around them. In the film’s beginning, it would appear that they find nothing in their surroundings worth it to them to stay close to any path that doesn’t include gang activity and, in turn, violent crime. If anything, the only thing anchoring any of the boys who join Darcy’s club to reality is the fear of their families, particularly their fathers. But it is a fear that includes resentment, and it is this resentment that causes the arrested development we can almost smell brimming within each of them. Darcy plays on this—but in a way that is benevolent, not abusive. He gives the boys a father they can trust, a father who will tell them when they’re being bullheaded, who will tell them when they’re wrong in their actions or words, but who will forgive them in turn almost instantaneously. When the boys get out of hand, he preaches to them, “Boxing is about control. Whatever you do in here, you do it with control.” When one of the boys overdoses, Darcy breaks in and nurses him back to health, selfless and quiet in his actions, like a guardian angel. When one of the fathers, the club’s sponsor, angered by his exclusion from a promotional article in the local papers, loses control and splits Darcy’s head open, he does not react in kind. Instead he holds a cloth to his head and sits quietly in the Emergency Room waiting area between the father and his girlfriend while they squabble about the nature of the term “accident.” So when one of the other boys’ father attends their tournament match and violently attempts to disrupt his son’s involvement in the proceedings, making a scene in the process, it is too much for Darcy, to see the work he’s done, the love he’s given these surrogate sons of his lain to waste by one drunken sod’s abusive hands. It is in this moment that his love for the boys betrays a violence in himself, brought to a simmering boil and too pressurized to be contained any longer. He loses control himself, nearly kills the man in the alleyway outside the gym, only to be beset upon by the entire club, who angrily ask of him, “Who do you think you are?” The boys set fire to the gym, and Darcy whiles away the rest of his days as a vagrant, only to be rescued before his death by the same boy whose honor he wished to cherish and defend, and who in turn he unintentionally disgraced.

In Shane Meadows’ sophomore outing Twenty Four Seven, Hoskins plays a man named Alan Darcy, committed to helping the wayward youth of his crumbling, decrepit factory community to regain their sense of self and purpose, through the auspices of a boxing club revival, one which he credits with providing himself and others like him with a similar impetus to change his ways as an adolescent. The teens are surly, far from kind to each other, and, to be blunt, brutal in a particularly British way, reserving no charity or restraint for themselves or the world around them. In the film’s beginning, it would appear that they find nothing in their surroundings worth it to them to stay close to any path that doesn’t include gang activity and, in turn, violent crime. If anything, the only thing anchoring any of the boys who join Darcy’s club to reality is the fear of their families, particularly their fathers. But it is a fear that includes resentment, and it is this resentment that causes the arrested development we can almost smell brimming within each of them. Darcy plays on this—but in a way that is benevolent, not abusive. He gives the boys a father they can trust, a father who will tell them when they’re being bullheaded, who will tell them when they’re wrong in their actions or words, but who will forgive them in turn almost instantaneously. When the boys get out of hand, he preaches to them, “Boxing is about control. Whatever you do in here, you do it with control.” When one of the boys overdoses, Darcy breaks in and nurses him back to health, selfless and quiet in his actions, like a guardian angel. When one of the fathers, the club’s sponsor, angered by his exclusion from a promotional article in the local papers, loses control and splits Darcy’s head open, he does not react in kind. Instead he holds a cloth to his head and sits quietly in the Emergency Room waiting area between the father and his girlfriend while they squabble about the nature of the term “accident.” So when one of the other boys’ father attends their tournament match and violently attempts to disrupt his son’s involvement in the proceedings, making a scene in the process, it is too much for Darcy, to see the work he’s done, the love he’s given these surrogate sons of his lain to waste by one drunken sod’s abusive hands. It is in this moment that his love for the boys betrays a violence in himself, brought to a simmering boil and too pressurized to be contained any longer. He loses control himself, nearly kills the man in the alleyway outside the gym, only to be beset upon by the entire club, who angrily ask of him, “Who do you think you are?” The boys set fire to the gym, and Darcy whiles away the rest of his days as a vagrant, only to be rescued before his death by the same boy whose honor he wished to cherish and defend, and who in turn he unintentionally disgraced.

I watched Twenty Four Seven again late last night, after hearing of Hoskins’ passing. There is, near the picture’s close, a funeral scene for Darcy. All the boys are there, in attendance, with their families, some healed, some minus members, and all of them fully grown and come into their own—and yet, in spite of everything that’s happened, not one of them wavers in his devotion to Darcy. I couldn’t help feel that after a life’s work so predicated towards violence and restraint, towards the understanding of those two vastly disparate poles, that there could ever have been a more appropriate last dance for the man at hand. I hope we’ll all remember him the same. A soft soul, perhaps, but burning brightly.

— Evan Louison