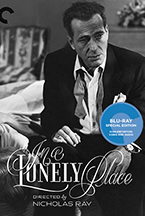

THE CURBSIDE CRITERION: IN A LONELY PLACE

(We here at Hammer to Nail are all about true independent cinema. But we also have to tip our hat to the great films of yesteryear that continue to inspire filmmakers and cinephiles alike. Our “The Curbside Criterion” column is where HtN staff can trot out thoughts on some of the finest films ever made. To mark this week’s Criterion Blu-ray and DVD releases of Nicholas Ray’s In A Lonely Place, Nelson Kim has revised his 2009 HtN piece on the film.)

Some classics sit decorously behind their glass display cases, while others aren’t safe to be left alone with at night. Nicholas Ray’s 1950 noir In A Lonely Place is the second kind. This corrosively brilliant tale of thwarted love, now out in new DVD and Blu-ray editions from the Criterion Collection, inspired career-best work from its director as well as its two stars, Humphrey Bogart and Gloria Grahame. Bogart plays Dixon Steele, a middlingly successful Hollywood screenwriter with problems: a drinking problem, a violence problem, women problems, and violent-with-women-when-drinking problems. When a hat-check girl he entices to his apartment one night is found dead the next day, only the alibi provided by his neighbor, Laurel Gray (Grahame), saves him from arrest. Laurel and Dix fall hard for each other, but soon she has reason to wonder whether the man whose innocence she fought for may, in fact, be guilty — and whether she may be his next victim.

Part of the enduring fascination of In A Lonely Place is how Ray (and screenwriter Andrew Solt) makes it work on so many seemingly contradictory levels. It’s a great and achingly romantic love story that also, no less than Hitchcock’s Vertigo, lays bare the possessiveness, the willful blindness, and the derangement of romantic obsession. It’s a portrait of an artist that valorizes the artist’s solitary stance against conformity even as it exposes the egotism of that stance. It’s a film noir in which the hard-boiled hero meets a mysteriously alluring beauty—and then, in one of the boldest audience-identification switcheroos I’ve ever seen in a movie, it subtly but definitively shifts our POV over to Laurel as her doubts about Dix take hold. We start out grooving to Bogie’s tough-guy routine, but by the end we’re practically pleading with Grahame to get away from him before she gets hurt, or worse.

By 1950 Bogart had already enjoyed nearly a decade as one of the industry’s top box-office draws, and his star persona was well established. For this movie, though, the star (and partial backer of the film, through his production company, Santana) fully committed to a ruthless deconstruction of his own image. It’s as if he and Ray were asking what the beloved Bogie figure would be like in real life, stripped of all Hollywood glamour and grace, and the answer is: an abusive, megalomaniacal drunk. Bogart was never afraid to be unlikable on-screen, and few leading men of any era carried the charge of danger he brought to his antihero roles, but playing Dix he plumbed unfathomed depths of ferocity. Along with everything else, In A Lonely Place offers the riveting spectacle of an actor seeming to reveal the darkest recesses of his own personality to the camera.

In this, he was guided and abetted by a director who identified to no small degree with both actor and character. Bogart’s friend Louise Brooks wrote that Dix’s “pride in his art, his selfishness, his drunkenness, his lack of energy stabbed with lightning strokes of violence were shared by the real Bogart.” But Ray had at least the first three of those qualities in common with Bogart, and there were other likenesses as well: a history of highly turbulent relationships exacerbated by their own erratic or self-destructive tendencies (Ray’s marriage to Grahame broke up during the shooting of In A Lonely Place); leftist political sympathies that they were pressured to disavow at the height of the HUAC hysteria; a healthy contempt for the artistic constraints imposed by the studio system, tempered by an acute awareness of the compromises they had made to succeed within it. Dix boasts he never watches any of the movies he’s written, but in a more vulnerable moment he says, “One day I’ll surprise you and write something good.” That could easily be the Bogart who came to stardom late, after years of playing heavies in mostly forgettable throwaways, or the Ray who described himself as “the best damn filmmaker in the world, who has never made one entirely good, entirely satisfactory film.”

In this, he was guided and abetted by a director who identified to no small degree with both actor and character. Bogart’s friend Louise Brooks wrote that Dix’s “pride in his art, his selfishness, his drunkenness, his lack of energy stabbed with lightning strokes of violence were shared by the real Bogart.” But Ray had at least the first three of those qualities in common with Bogart, and there were other likenesses as well: a history of highly turbulent relationships exacerbated by their own erratic or self-destructive tendencies (Ray’s marriage to Grahame broke up during the shooting of In A Lonely Place); leftist political sympathies that they were pressured to disavow at the height of the HUAC hysteria; a healthy contempt for the artistic constraints imposed by the studio system, tempered by an acute awareness of the compromises they had made to succeed within it. Dix boasts he never watches any of the movies he’s written, but in a more vulnerable moment he says, “One day I’ll surprise you and write something good.” That could easily be the Bogart who came to stardom late, after years of playing heavies in mostly forgettable throwaways, or the Ray who described himself as “the best damn filmmaker in the world, who has never made one entirely good, entirely satisfactory film.”

The movie was loosely adapted from Dorothy B. Hughes’ 1947 novel, a superb piece of noir storytelling and a still-potent cocktail of toxic misogyny and madness that in one important respect goes farther than the film. Hughes’ Dix is a serial rapist and killer, and no American movie at the time could feature such a character as a sympathetic lead. So Bogie’s Dix is instead a man who might commit murder in a drunken rage, not one with a trail of bodies behind him. You could call this a typical case of Hollywood bowdlerization—except that “typical” is the last word anyone would use to describe the quality of feeling in Ray’s film. If the novel’s bold exploration of psychopathology went missing in the transition to the screen, it was replaced by a startlingly candid depiction of narcissism, neediness, shame, and self-loathing; if Hughes aimed for a pulp Crime and Punishment, Ray came as close as any director ever has to creating a cinematic equivalent to Notes from Underground.

Movie and book differ in one other crucial way. The novel’s Laurel is a shadowy figure, filtered through Dix’s guiding consciousness, whereas Ray, Solt, and Grahame make her the beating heart and conscience of the story. The affair between Dix and Laurel is hot stuff in the book, but the film elevates it to the level of tragedy. Ray and Grahame’s marriage seems to have been ill-fated from the start—”I was infatuated with her, but I didn’t like her very much,” he observed—and it ended scandalously: they separated during production, but the final split came afterward, when Ray found her in bed with his thirteen-year-old son from his first marriage. (Several years later, Grahame and Tony Ray married and had two children.) And yet, In A Lonely Place ultimately belongs as much to Grahame/Laurel as it does to Bogart/Dix. The film can be seen as Ray and Bogart’s statement on malignant masculinity, but it’s through Grahame’s eyes that we measure the pain caused and the losses suffered: so many of its strongest scenes are propelled by her wounded reactions to Bogart’s behavior, and Laurel’s voice is the last one we hear at movie’s end as she repeats a few lines Dix had spoken earlier, transforming his maudlin romanticism into a melancholy goodbye to romantic love and its sweet illusions:

Movie and book differ in one other crucial way. The novel’s Laurel is a shadowy figure, filtered through Dix’s guiding consciousness, whereas Ray, Solt, and Grahame make her the beating heart and conscience of the story. The affair between Dix and Laurel is hot stuff in the book, but the film elevates it to the level of tragedy. Ray and Grahame’s marriage seems to have been ill-fated from the start—”I was infatuated with her, but I didn’t like her very much,” he observed—and it ended scandalously: they separated during production, but the final split came afterward, when Ray found her in bed with his thirteen-year-old son from his first marriage. (Several years later, Grahame and Tony Ray married and had two children.) And yet, In A Lonely Place ultimately belongs as much to Grahame/Laurel as it does to Bogart/Dix. The film can be seen as Ray and Bogart’s statement on malignant masculinity, but it’s through Grahame’s eyes that we measure the pain caused and the losses suffered: so many of its strongest scenes are propelled by her wounded reactions to Bogart’s behavior, and Laurel’s voice is the last one we hear at movie’s end as she repeats a few lines Dix had spoken earlier, transforming his maudlin romanticism into a melancholy goodbye to romantic love and its sweet illusions:

I was born when she kissed me

I died when she left me

I lived a few weeks while she loved me

— Nelson Kim