(Close-up is available on DVD and Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection.)

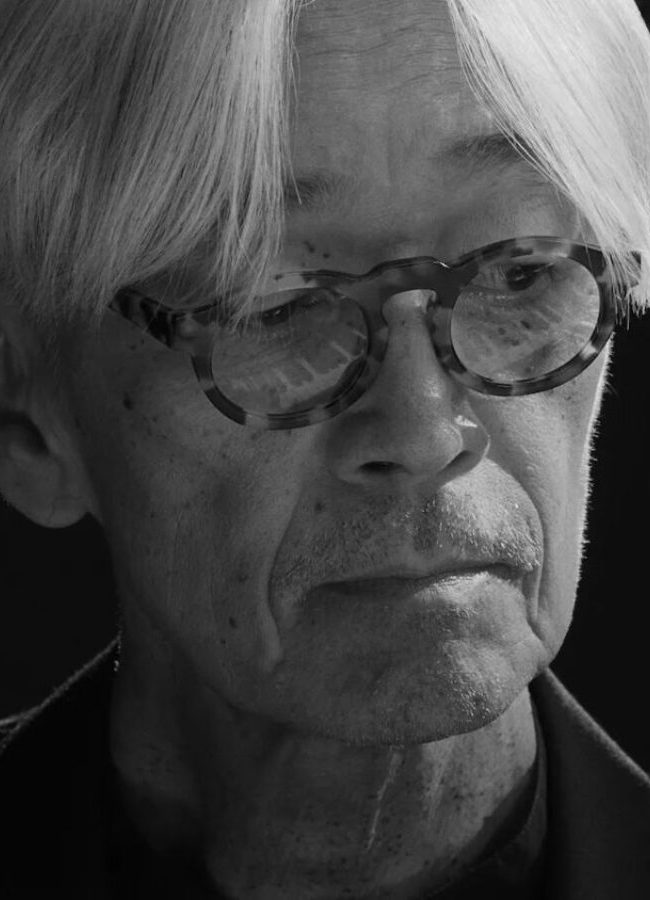

“Close-up is present in some way in every film I make. At the least, my standards for the acting, for the screenplay, for people’s inner conflicts, are measured against my standards in Close-up. That way I find out how close I am to reality in the film I’m working on.”

So says Abbas Kiarostami in a recent video interview accompanying the new Criterion edition of the film that launched his name in the West. When Close-up began playing the international film festival circuit in 1990, Kiarostami was still little known outside his native Iran; by the close of the decade Phillip Lopate would write, “[W]e are living in the age of Kiarostami, as we once did in the age of Godard.” Godard himself, never one to make a modest claim when a world-historical one would do, said, “Film begins with D.W. Griffith and ends with Abbas Kiarostami.” Such judgments were formed during a time when Kiarostami was regularly turning out one astonishing film after another: Life and Nothing More and Through the Olive Trees (the second and third parts of what would evenually become known, along with 1987’s Where Is the Friend’s Home?, as the “Koker trilogy”), Taste of Cherry, The Wind Will Carry Us. But none of his works has achieved greater esteem among cinephiles than Close-up. How does the movie look 20 years later, especially now that its director’s reputation has, perhaps inevitably, declined a bit from its 1990s peak? Does Close-up still deserve its exalted status? Is the Ayatollah Islamic?

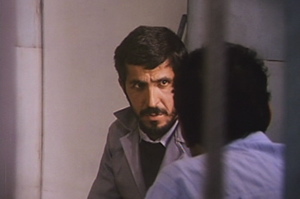

For the uninitiated: the story began when Kiarostami read an article about Hossein Sabzian, a broke, unemployed, movie-mad divorcé who had been arrested for impersonating the filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Sabzian had used this false identity to win the confidence of the Ahankhahs, a middle-class Tehran family. Over the course of a few days, Sabzian visited the Ahankhahs repeatedly, saying he planned to cast them in his next film and wanted to use their house as a location for shooting. When the family became suspicious, they called the police and later pressed charges. Kiarostami immediately decided to make this the subject of his next film. He conducted interviews with the principals, received permission to record the trial, and in his most daring conceptual leap, persuaded both the con man and his dupes to play themselves in reenactments of the impersonation and its aftermath.

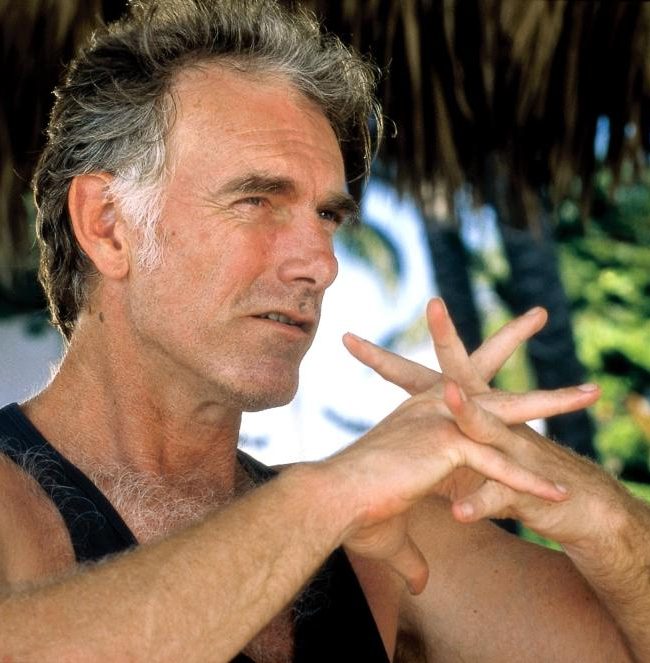

Close-up blends the interviews, the courtroom footage, and the reenactments into an intricate, shifting, endlessly subtle investigation of truth-telling and fiction-making. As Kiarostami puts it in the Criterion video interview, “it’s like a prism: no matter what angle you look from, it shows you a reality you can’t predict.” The reenactments are obviously staged, but they draw on what the participants claimed were their actual words and actions at the time of the original events. The trial scenes are “real,” but according to Godfrey Cheshire’s informative essay written for the Criterion package, Sabzian’s long courtroom speeches were partly scripted by Kiarostami (although based on Sabzian’s earlier statements). Other moments in the film are head-scratchingly complex fusions of factual and falsified, such as the real Makhmalbaf’s surprise appearance late in the film, which Kiarostami prearranged specifically to provoke a spontaneous outburst of emotion by Sabzian, but which he then altered in postproduction because he wasn’t satisfied with Makhmalbaf’s “performance.” (Makhmalbaf would later borrow heavily from Close-up‘s formal innovations for his 1996 opus A Moment of Innocence, a far less well-known film in these parts but, in my view, an equally imperishable masterpiece.)

Close-up blends the interviews, the courtroom footage, and the reenactments into an intricate, shifting, endlessly subtle investigation of truth-telling and fiction-making. As Kiarostami puts it in the Criterion video interview, “it’s like a prism: no matter what angle you look from, it shows you a reality you can’t predict.” The reenactments are obviously staged, but they draw on what the participants claimed were their actual words and actions at the time of the original events. The trial scenes are “real,” but according to Godfrey Cheshire’s informative essay written for the Criterion package, Sabzian’s long courtroom speeches were partly scripted by Kiarostami (although based on Sabzian’s earlier statements). Other moments in the film are head-scratchingly complex fusions of factual and falsified, such as the real Makhmalbaf’s surprise appearance late in the film, which Kiarostami prearranged specifically to provoke a spontaneous outburst of emotion by Sabzian, but which he then altered in postproduction because he wasn’t satisfied with Makhmalbaf’s “performance.” (Makhmalbaf would later borrow heavily from Close-up‘s formal innovations for his 1996 opus A Moment of Innocence, a far less well-known film in these parts but, in my view, an equally imperishable masterpiece.)

Kiarostami’s radical narrative approach harmonizes beautifully with his film’s deeper meanings, which have to do with the mystery of human motives, the mutability of truth, and our profound need for fiction, for imposture, for lies—the kind we see on screen, the kind we tell each other and ourselves. The Ahankhahs claim Sabzian was casing their house for a planned burglary; he insists he was only seeking the “attention and respect” he lacked in his own life. At the trial, Sabzian drops the Makhmalbaf mask and speaks openly and very movingly of his pain and despair, but one of the Ahankhah children declares that this, too, is a pose. Kiarostami gently suggests from off-camera that perhaps Sabzian might be better suited to acting than directing; Sabzian allows that he may have a point. When every layer of falsehood appears to have been stripped away, and every ego-protecting defense mechanism has been penetrated, there’s another layer, then yet another.

Kiarostami’s radical narrative approach harmonizes beautifully with his film’s deeper meanings, which have to do with the mystery of human motives, the mutability of truth, and our profound need for fiction, for imposture, for lies—the kind we see on screen, the kind we tell each other and ourselves. The Ahankhahs claim Sabzian was casing their house for a planned burglary; he insists he was only seeking the “attention and respect” he lacked in his own life. At the trial, Sabzian drops the Makhmalbaf mask and speaks openly and very movingly of his pain and despair, but one of the Ahankhah children declares that this, too, is a pose. Kiarostami gently suggests from off-camera that perhaps Sabzian might be better suited to acting than directing; Sabzian allows that he may have a point. When every layer of falsehood appears to have been stripped away, and every ego-protecting defense mechanism has been penetrated, there’s another layer, then yet another.

Close-up Long Shot, a 1996 documentary portrait of Sabzian included as a supplement on the Criterion disc, reveals an even more troubled soul than the sympathetic screwup of Kiarostami’s film, a man whose passion for movies seems to have made a mess of his life. “I may be one of cinema’s victims,” he says in the documentary, as if writing his own epitaph (in fact, he died in 2006). “I intended to devour cinema and it ended up devouring me.” Not the least of Close-up‘s multiple ironies is that it has granted this would-be artist the artistic greatness he craved: Sabzian will live for generations as a mirror image of our own desperate, death-haunted hunger for significance.

— Nelson Kim

Alex Hansen

A very nice write-up. Thank you.

Pingback: THIS IS NOT A FILM – Hammer to Nail