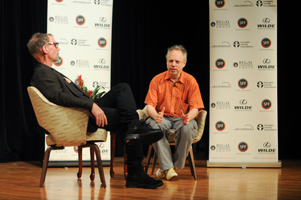

“In Conversation With Todd Solondz” (w/ David Carr at the 2012 Sarasota Film Festival)

[This “In Conversation With Todd Solondz” took place on Sunday, April 22, 2012, as part of the 2012 Sarasota Film Festival. This goal of this transcription was to preserve everything that was said while containing the necessary clean-up that would enable things read more smoothly. Special thanks to Artistic Director/HTN contributor Tom Hall for allowing us to post it here, as well as to David Carr and Todd Solondz for their thoughtfulness and intelligence.]

David Carr: We had an opportunity to chat yesterday, and I was struck not just by your openness but by your curiosity about all things, the breadth of human experience. I thought, “He’s so sweet and so nice and bright,” and then I thought, but you make movies, and you make movies the hard way. When it gets time to sort of get the funding together and direct people do you, like, sprout another head and suddenly turn into an asshole? Or are you nice all the time?

Todd Solondz: I think it’s important always to be polite, amongst our colleagues and people you meet and so forth. But I think it’s important to not be so polite when you are writing, when you are actually writing a script or making a movie. It’s emphatic that your work not be polite. As a filmmaker, you have two jobs. One is the work that you create, the film. And then there’s also the part of you that has to be aware of the business of film—I try to delegate as much of that to the producer that I work with. But I don’t think you can survive as a filmmaker without being aware of both aspects of the nature of filmmaking. Because unlike writing a book, it just requires a lot of money.

DC: But when you sort of gather this temporary village that you have to make a movie—I mean, you work with not a pencil but an 800-pound pencil—there’s an apparatus that goes with filmmaking that requires not just collaboration, but leadership. In the instance of Dark Horse, you cast Christopher Walken, who totally kills it; he’s amazing. But I think of that as you having to be something of a lion tamer. You’ve worked with some of the greatest actors of our generation and each of them has separate needs. When you’re on set, do you think of yourself as a lion tamer, or a nursemaid, or both? How do you keep everybody happy?

TS: I don’t know that I always succeed, but when it comes to the performers, my job is to get the performance that I need from my actor up on to screen. So whatever it takes, I’ll do it. If an actor needs me to hold their hand, I hold their hand. If they want me to stay away, don’t talk? Okay, peace, I don’t talk. As long as I get what I need, that’s the critical thing. And you always have to maintain, even at the end, a cordial relationship with your actor, because oftentimes you may need them—you don’t know for sure—in the post-production process. Maybe many months later. But most everybody I’ve worked with on the productions of my films, I would work with again.

DC: Do you think they’d feel the same way about you?

TS: I don’t know, though maybe not. [audience laughs]

DC: I’m not saying that in a smarty-pants way. But I think you’re known as an actor’s director. People like working with you.

TS: I’ve had mostly gratifying experiences. As a director, you have to always assess the character of the person you’re working with as quickly as possible, so that you know how to talk to that person, what to say, what not to say, what buttons to push and what buttons not to. I’m not aware of any actor I’ve worked with that would not work with me, but I don’t know.

DC: I feel like I know a little something about directing because at least that’s storytelling so that’s something that I can see from what I do. I’ve never really understood acting. I covered the Oscars for four years, and the range of intellect—and I’m not trying to be smarty-pants here—but you would go from incredibly brilliant, super-smart people to people who didn’t seem to have the IQ of a box of donuts. And yet when it came time for them to manifest their craft, they were all in their own way very good at it. Do you think acting correlates to intelligence or not?

TS: Well it’s a form of intelligence. It is a gift, and it’s something that you are very much aware of through the audition process. Almost all of my actors, 90% of them, have all read for me. And you see so many actors that when someone makes you really wake up and listen, it’s something very special when that happens. Sometimes I think, “Is there something wrong with my writing?” Because it’s just not happening. I’ve seen 20, 30 actors, and it’s just never popping. And then someone comes in, and all of a sudden it takes on a life, and you say, “Ahh!” It’s just finding the right actor for the right part.

TS: Well it’s a form of intelligence. It is a gift, and it’s something that you are very much aware of through the audition process. Almost all of my actors, 90% of them, have all read for me. And you see so many actors that when someone makes you really wake up and listen, it’s something very special when that happens. Sometimes I think, “Is there something wrong with my writing?” Because it’s just not happening. I’ve seen 20, 30 actors, and it’s just never popping. And then someone comes in, and all of a sudden it takes on a life, and you say, “Ahh!” It’s just finding the right actor for the right part.

I had an experience with Chris Penn years ago, who I think was a really remarkably talented, intuitively, instinctively gifted performer. And he had a complicated, difficult life in a way. It was a very painful experience because he really was giving me great work, but I had to fire him. What was interesting about him was he had a kind of idiot savant sort of quality. But he responded to certain aspects of the script with certain questions. I don’t think any other actor [has ever] made me rethink a part the way he did, and made me rewrite it and make it better, because of certain instinctive responses he had to the material. At the same time, there were other suggestions that were cockamamie. But you politely listen and dismiss [them]. You know, “Yes, we’ll do that, but let’s focus on something else.” And so you take the good, because you don’t want anyone to feel bad if you don’t really subscribe to their creative ideas. But he was a situation where I had to fire him because he just couldn’t function because he had a certain kind of drug problem, and he really could not function. I’ve worked with functional alcoholics and that’s been okay. But it’s just only when it becomes non-functioning. So it was very painful because had he not been doing such fine work it would have been a very easy decision. But because of how gifted—there was something very moving about him—it was a very, very painful one.

DC: In your world, the arrangement you’ve made is you’re a professor at NYU and you teach. And I know from talking to your students that you’re a gifted teacher and you care about what they do, and people love listening to you. You’re good at it. You’re sending some people out into the world that have a little more skill than they did before they met you, which is deeply satisfying. At the same time, a lot of people in your position that are making movies that are not popcorn movies, what they’ll do is they’ll either make a movie, or more often television, where they’ll go in and they’ll hand-crank a bunch of television or a film that will enable their own work. And so it’s sort of “one for them, one for me, one for them, one for me.” You know, you’ve got a great deal of skill as a director that I’m sure would be fairly marketable, but you really haven’t gone that way.

TS: It is a golden age for television now. There’s a lot of very fine work and writing that is broadcast as never before, really. And yet I have no interest in directing an episode of one of these successful TV shows, because I feel that it’s not a form that’s designed for the director. It’s really a writer’s game. And why hire me? There are people who would be much more adept and much more knowledgeable about the television show than I am. So it just never interested me. You say “one for me, one for them, one for me, one for them,” but there are very few filmmakers, period, who work outside of the system in this country at all. You know, if you make one movie in the ‘90s and another movie in the aughts, once every ten years, it’s hard to characterize that, really, as a career. It’s economic forces that are at work in making filmmakers like myself very scarce. Jarmusch still manages perhaps to cobble together some money. I think Hal Hartley’s had a very hard time. There are a few, really just a handful of filmmakers, who you could say over 20 years, let’s say, have made a reasonable amount of work. If I were French and had citizenship there, it wouldn’t be an issue. I would have a career, because they have subsidies for filmmakers like myself. I think 10% of the ticket of a movie there goes towards a subsidy to support filmmakers. That doesn’t exist here. We’re driven solely by market forces. Claire Denis, who is something of an icon in France, perhaps if she had been American she might have been able to cobble together money for one movie. But certainly she could have never had a career in this country. She would have had to either direct episodic [TV] or teach or do commercials, because [our system] just doesn’t support that kind of work.

TS: It is a golden age for television now. There’s a lot of very fine work and writing that is broadcast as never before, really. And yet I have no interest in directing an episode of one of these successful TV shows, because I feel that it’s not a form that’s designed for the director. It’s really a writer’s game. And why hire me? There are people who would be much more adept and much more knowledgeable about the television show than I am. So it just never interested me. You say “one for me, one for them, one for me, one for them,” but there are very few filmmakers, period, who work outside of the system in this country at all. You know, if you make one movie in the ‘90s and another movie in the aughts, once every ten years, it’s hard to characterize that, really, as a career. It’s economic forces that are at work in making filmmakers like myself very scarce. Jarmusch still manages perhaps to cobble together some money. I think Hal Hartley’s had a very hard time. There are a few, really just a handful of filmmakers, who you could say over 20 years, let’s say, have made a reasonable amount of work. If I were French and had citizenship there, it wouldn’t be an issue. I would have a career, because they have subsidies for filmmakers like myself. I think 10% of the ticket of a movie there goes towards a subsidy to support filmmakers. That doesn’t exist here. We’re driven solely by market forces. Claire Denis, who is something of an icon in France, perhaps if she had been American she might have been able to cobble together money for one movie. But certainly she could have never had a career in this country. She would have had to either direct episodic [TV] or teach or do commercials, because [our system] just doesn’t support that kind of work.

DC: Yeah, but you made, depending on how you’re counting, seven important movies in 15 years. Are you skilled at performing cashectomies on people? Maybe it has to do with Ted Hope, maybe it has to do with who you’ve gathered around you, but given your model of filmmaking, you’ve been fairly prolific.

TS: Well, that’s a little too strong to say prolific—I still say “quasi-career”—but to make a half dozen movies, I could have made more I think if money were not an issue. But it is and I’ve just been very fortunate in coming across it. You know, I have another script, who knows if I’ll get money to make it. I always presume every movie I make is my last. My career is very smoothly in decline, each movie making half as much as the prior one.

DC: So the lesson being: don’t be a huge success coming out of the gate.

TS: No, that’s hardly a lesson. You always strive for success. I have people say they learned so much from failure, but I’ve always found I learn a lot more from success. Also, success opens doors; it’s very pleasant. And failure’s very painful. Sometimes you just throw up your hands and, “How did this happen?” And it certainly only closes doors. So much is luck and the alchemy, the forces. You know, will I get to make to make another movie? I just don’t know. I have to be very Zen about it and accept that I may never make another movie because money may never come my way again. But I like to be optimistic. The act of writing any sort of script or making a film is always a great gesture of optimism, a leap of faith, because you have some hope that maybe something wonderful will come of this. It’s a kind of marriage. You get married because you believe in that great possibility. There’s never any evidence, of course, that anything will work out. But you live on that hope, because it’s all so hard. The obstacles are all so crushing. It takes a kind of tenacity and conviction about one’s work that it has to be that worthwhile to put yourself through all of this.

DC: But hopefulness and optimism, I wouldn’t say, is a real theme of your work. [audience laughs]

TS: That’s true. [audience laughs louder] It’s a question of context always. Hope is kind of neutral. You know, it wasn’t good for the Jews going into the gas chamber to be hopeful. It’s all about context. Optimism, pessimism, they don’t have any meaning outside of context. But in terms of if that’s what’s going to help you write and get a movie made, it requires a certain amount of optimism.

I don’t see my movies as pessimistic or as bleak as others. It’s really a question of what you glean from it, the way in which you experience it. The tricky thing if you’re an aspiring filmmaker—and I can’t tell who’s out there, I can’t really see anyone [audience laughs], when you’re young in particular, the danger is always being clever. Cleverness is a facility some of us have, and we like to show off how smart we are. It’s a very dangerous kind of seduction. It’s sort of like when we have answering machines and leave a “clever” message. After a little while you get a little tired of it. It doesn’t have much staying power. “Let’s come up with a clever name for a production company!” And everyone thinks it’s really funny, and then you’re stuck with it and it gets on your nerves.

DC: What’s the name of your production company?

TS: It’s complicated because of the way things work, but I kept it simple. I have a “Small,” “Medium” and “Large.” I also have an “Extra Large,” but when we used “Extra Large” they thought we were pornographic so I keep it the other sizes.

The issue is what is it you’re in love with, what is it that compels you, what is it when you’re alone and not with all your cool and hip friends, what is it that really stirs you? That’s the stuff that is going to be compelling. What is it that embarrasses you, that you fear to expose about yourself, your feelings about others or about the world in which you live? It’s those intimate feelings one has that I think are going to bear the best fruit for you. You go to movies and I always find if you go in a group, your response to the film is often diluted because we all have a desire to conform to some extent to the group. And if you go with just one companion, even there there’s always a kind of negotiation in the way in which you respond to the work.

DC: I try and not talk first. I have a one-block rule. I don’t say anything. We went and saw Gayby yesterday, and I really like that film. I think Jon [Jonathan Lisecki] is here. I know his husband [author/New Yorker writer Alex Ross] so there’s a little additional pressure. Whenever you go to see a friend’s movie, what if it sucks, right? But I went with my family, which ranged from 14-years-old to I’m older than dirt—I’m so old I can’t even remember how old I am—and it gradually became clear a block away from the movie that we all loved it. But I’m sure if somebody had stepped up forcefully early and said, “Well, I’d like those two hours back,” that it would have tilted, as you say.

TS: The point I want to get at, though, is that we’re often told there are movies that we should like, movies that are hip to like, or movies that we want to like. And I think it’s important to really be truthful with yourself. What is it that really touches you? What movies really speak to you personally? And you don’t have to understand why. It doesn’t have to be a good movie. The Sound of Music was the first movie that I saw as a child, and I was in love with it as a five-year-old. It had a big impact. And I wouldn’t have been able to make the Sunshine Singers in Palindromes had I not been in love with the von Trapp singers in The Sound of Music. I think that the things that stick with us stick with us for reasons we may not understand. But we use that, and we reuse and reshape it to [meet] our own ends. So it takes time to figure out that it’s really hard to be truthful with yourself. You want to be in love with Bresson’s Pickpocket but really it’s a bit of a snooze for you. And really the kinds of movies that you’re in love with, your big secret is Julia Roberts’ My Best Friend’s Wedding and you’ve seen it 80 times. But it’s a secret. And it’s important to be in touch with who you are, to embrace that. If you want to make that Julia Roberts—your own kind of Julia Roberts—comedy, then pursue that! Don’t pretend to be in love with something that you’re not. When I was young, I went to movies in college, that’s where I discovered movies, because it was before even VHS. They would be screened every night. You could see Bergman paired with the Marx Brothers paired with Maya Deren and so forth. And I just took it all in. I imbibed and imbibed everything, and I didn’t have to understand it. But the more you take in, the more you discover what sticks with you, and in unexpected ways movies can inform and help you when you’re on set. And I can illustrate that. I don’t want to go off too much if you want to…

DC: I love that we’re talking about significant artistic issues, and these people are here to listen to you, so please go on.

TS: There’s [a] curious story of when I made Welcome to the Dollhouse, there was a scene in the script where the bully corners Dawn Wiener, the protagonist, in a stairwell. It was written very shadowy and dark, and when we actually got into production and we were fortunate enough to find a location that would allow us in, we got a school that didn’t have any stairwells. It was really a genius of an architect who designed it, because there wasn’t a single corner in the whole school. It was bully-proof. I couldn’t figure out if I were a bully, like where would I go and slug someone? There were no corners. So it was a bit of a problem, a conundrum. How do I solve that? And in the most oblique way, I then remembered the famous scene from North by Northwest in the cornfield, where suspense is created through light and space. And so what I did was I moved the scene outdoors. I moved it by the exit outside, so that when you look over the bully’s shoulders, I put a soccer game in the background, so that while he’s threatening the poor girl with a knife, we see behind his shoulder in the background a beautiful sunny day, children playing soccer, having a lovely time, having fun, and innocence. And it becomes a scene in which it’s complicitly understood: the world doesn’t care. The world goes about its wonderful business, even as you experience this sheer terror. It’s an illustration of the funny ways in which movies, from all that you take in and that you read and that you see, helps you at those critical moments. And you say, “Oh, I can steal that!”

TS: There’s [a] curious story of when I made Welcome to the Dollhouse, there was a scene in the script where the bully corners Dawn Wiener, the protagonist, in a stairwell. It was written very shadowy and dark, and when we actually got into production and we were fortunate enough to find a location that would allow us in, we got a school that didn’t have any stairwells. It was really a genius of an architect who designed it, because there wasn’t a single corner in the whole school. It was bully-proof. I couldn’t figure out if I were a bully, like where would I go and slug someone? There were no corners. So it was a bit of a problem, a conundrum. How do I solve that? And in the most oblique way, I then remembered the famous scene from North by Northwest in the cornfield, where suspense is created through light and space. And so what I did was I moved the scene outdoors. I moved it by the exit outside, so that when you look over the bully’s shoulders, I put a soccer game in the background, so that while he’s threatening the poor girl with a knife, we see behind his shoulder in the background a beautiful sunny day, children playing soccer, having a lovely time, having fun, and innocence. And it becomes a scene in which it’s complicitly understood: the world doesn’t care. The world goes about its wonderful business, even as you experience this sheer terror. It’s an illustration of the funny ways in which movies, from all that you take in and that you read and that you see, helps you at those critical moments. And you say, “Oh, I can steal that!”

DC: You know, I characterize your work as perhaps not optimistic or hopeful, but I do think that the sort of redemptive power of the human spirit and the durability of it is manifest in what you’ve done. What I’m interested in, though, is how you are like a dog on a meat bone. When you get on something you don’t necessarily let go of it. In Palindromes, you’re kind of doing a character eight different ways. In Life During Wartime, you’re revisiting not just thematically, but story-wise, Happiness. There’s a persistence of concerns in your work, where there are certain things that engage you. I hadn’t seen Dark Horse before I came here, and I thought, “Hmm, boy-meets-girl… Todd Solondz… that’ll be interesting.” And the set-up is a cue that you’re about to see a Judd Apatow movie—a filmmaker I adore, unironically. I sit there in the third row with a big bucket of popcorn and just love every second of it. So you have a large oafish character that sort of refuses to grow up, but he doesn’t warm up as he goes. I mean, life continues to anneal him, and come after him, either in actual life or character conversations conjured by him, [where] people take his measure and say, “You’re a schmuck. You’re lazy. You don’t do anything.” And it shows that he knows it, but it doesn’t really show him learning, does it?

TS: What interests me is this is a character living a kind of pathology—a pathological condition, really—who resists growing up. And his mother mothers him, you know, [she] treats him like a child. And he’s in a rage inside because he’s in great pain at the same time. And I never want to soften the truth of what a character’s about. My aim, rather, the hope is that by the end of the film, the audience will come to look at him in a different way. That for all the bluster, for all the obnoxiousness, let’s say, that there is a kind of pulse, a human soul struggling and bleeding. And that moves me. I want the audience to be able to get there. I don’t want to soften him up for the audience.

TS: What interests me is this is a character living a kind of pathology—a pathological condition, really—who resists growing up. And his mother mothers him, you know, [she] treats him like a child. And he’s in a rage inside because he’s in great pain at the same time. And I never want to soften the truth of what a character’s about. My aim, rather, the hope is that by the end of the film, the audience will come to look at him in a different way. That for all the bluster, for all the obnoxiousness, let’s say, that there is a kind of pulse, a human soul struggling and bleeding. And that moves me. I want the audience to be able to get there. I don’t want to soften him up for the audience.

DC: Yeah, you make that a big part of your work.

TS: For me, that’s more compelling an experience. Maybe the audience’ll fight it—“I don’t like you; I don’t like him; I dismiss him”—but I want to make it maybe not so easy to dismiss this person, who I feel for. Every time there’s just a shot of him after his failed romantic overtures, just him walking to his room, I’m moved even by that.

DC: As was I, because he proposes marriage compulsively to a woman who’s essentially a zombie. I mean, who is either on meds or so traumatized about what she’s been through. But part of me, when he did that, it’s like, “Okay, you’re clumsy, you’re stupid, you don’t really know where you are, you’re not hip to the ways of the grown world, but you are going for it, you are trying.”

TS: Exactly. I respect him for putting himself out there, but he puts himself [out there] in a way that’s doomed. There’s a kind of desperation in the way he goes about it. He wants to grow up [yet] he’s afraid of growing up. In some sense, he invites failure. And, you know, this is a character who talks about how horrible mankind is and how everybody’s so terrible.

DC: He makes that speech to his mother, played by Mia Farrow.

TS: Yes, yes. How terrible people are. And yet the movie does serve to undermine this worldview, for, in fact, right there in his workplace, there is a woman who cares for him, who pines for him, who has affection for him, and to whom he is blind. This is what, for me, is what is tragic, you see. Everything else, it’s a kind of death trip. It’s a guy who’s cornered, and trapped, and trying to find an escape to become not a man-child but a man. I wanted it, just like you say, to appear as if we’re watching an Apatow film, as if we’re watching a slacker, joint/pot-smoking, “arrested development” kind of cuddly character. But to try and look at it in a way that doesn’t require me to gross one hundred million.

DC: Although that wouldn’t be bad either. One of the things I noticed is that you used very familiar tropes, in terms of, “Okay, the parents are watching TV; here’s the overgrown son going to the bedroom.” We’ve seen that. We’ve seen that office before. And so there’s all these sitcom needs, but they’re shot almost radioactively.

TS: In fact, I saw this as a kind of counterpart, a kind of counter-life, to Seinfeld, to the Jason Alexander character and his parents on that TV sitcom. So what I did was, I have the parents watching Seinfeld—but we could never afford Seinfeld—so I wrote some dialogue and I had Jason Alexander and Jerry Stiller and Estelle Harris, they all came in and recorded lines and we created our own Seinfeld.

DC: Smart.

TS: So nobody can tell the difference, you know.

DC: Right.

TS: But the idea was that [Seinfeld is] the funny, comical version, and this is the counter-life.

DC: I came up here without asking if we were gonna do an audience Q&A and how long we long we were gonna go, so your host has failed you. But I’m assuming there are questions in the audience. I don’t just wanna go on and on and on. We really cannot see you guys. Do you have questions for Todd?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I have a question that both of you can answer. In the Academy Awards and other honors that are given to the actors, how much does their political belief deal with who gets the award and so forth?

[TS immediately motions to DC that this question is all his.]

DC: Wow, thank you for the hot potato, Todd. I do think that the sort of crunchy, vaguely progressive LA political dynamic does play a role. How did Crash come out of nowhere—Paul Haggis is a great filmmaker, but how did it come out of nowhere? Well, it was about cars and LA, and it was about races getting along and not getting along, and so it had all buttons… I’m trying to think, if you think of the Screen Actors Guild, I would say it’s sort of like media in general, if you had to give them a tube test, you’d find out there are a lot more Democrats then there are Republicans. But let’s think about this for a minute. Did Charlton Heston ever win? Do you know?

TS: I think he did. Bo Derek, though. [H2N laughs loudest]

DC: What about Mel Gibson, has he won?

Multiple Audience Members: Yes.

DC: He won. You know what, I covered the Oscars for four years, and trying to make sense out of how things happened, I got lucky the first year in predictions and I was just terribly wrong afterwards. And part of the reason that I quit covering the Oscars is there’s an entire hundred million dollar industry arraigned over the Oscars—the parties, the spending, and the paper I work for makes money off of it, so I’m not suggesting all of those guys are horrible. We certainly participate in it. But I’m the kind of person, if there’s a movie here, I wanna be in the third row, with some popcorn, and there in time for the trailers, and I always think it’s gonna be great. I’m always ever hopeful that it’s gonna be wonderful. And when you get involved in the Oscars, you just can’t overestimate the level of cynicism that’s going on. The business that goes with the show is breathtaking. And that’s what I came away with more than thinking about how much politics had to play in it. Who else has a question? Go ahead, young lady.

Audience Member: Very cool shoes, both of you, by the way. Very nice choice in footwear today.

DC: Thank you. Mine are sorta new so I appreciate it.

Audience Member: Yeah, black on black, very nice. Sunshine yellow, too [re: Solondz’s Converse All-Stars]. My question is about Happiness. I hope to write for the screen one day, so I’m curious about your process. Particularly with regards to Happiness as it is sort of a collection of all these different people’s stories arranged as vignettes and then scrambled together. So how did you do that? Did you, like, write Philip Seymour Hoffman’s character one week, and then the pedophile the next? Or was it just little snippets coming from all over? And how long did it take you?

TS: I don’t know, it probably took me 30 years. [audience laughs] When you write anything, your ideas, your stories, they incubate, and the actual literal writing may take six weeks. If you wrote three pages a day, you’d have three feature scripts a year—but the brain doesn’t really work quite so tidily as that. That script, I just started at the beginning as I normally do, I suppose. I just started at the beginning and kept writing. What I did was, I think I wrote 30 pages, and then what I liked to do at that point was show it to a friend that I trusted. And I had one question: Do you want to keep reading? Do you want to know what happens next? And they said yes, so then I gave [them] another 30 pages. They said, “Yes, lemme see what goes on, what happens next.” Because I was a little nervous about the subject matter I was dealing with. But I wanted to know on a story level, did they wanna know what happens next? And so that’s how I got to the end of the script. After the success of Welcome To The Dollhouse, you know, every door was open to me, and I wasn’t accustomed to success. I suppose I was a little bit uncomfortable, in fact, with all of that success, so I wrote something that I thought would close every door. [audience laughs]

TS: I don’t know, it probably took me 30 years. [audience laughs] When you write anything, your ideas, your stories, they incubate, and the actual literal writing may take six weeks. If you wrote three pages a day, you’d have three feature scripts a year—but the brain doesn’t really work quite so tidily as that. That script, I just started at the beginning as I normally do, I suppose. I just started at the beginning and kept writing. What I did was, I think I wrote 30 pages, and then what I liked to do at that point was show it to a friend that I trusted. And I had one question: Do you want to keep reading? Do you want to know what happens next? And they said yes, so then I gave [them] another 30 pages. They said, “Yes, lemme see what goes on, what happens next.” Because I was a little nervous about the subject matter I was dealing with. But I wanted to know on a story level, did they wanna know what happens next? And so that’s how I got to the end of the script. After the success of Welcome To The Dollhouse, you know, every door was open to me, and I wasn’t accustomed to success. I suppose I was a little bit uncomfortable, in fact, with all of that success, so I wrote something that I thought would close every door. [audience laughs]

DC: It worked a little bit. I mean, choosing a pedophile as sort of your hero.

TS: I don’t know that I would call him a hero.

DC: Your main character.

TS: I’m not even gonna say “the main character.” But certainly the one that was the most shocking, I think, for audiences, the way in which the pedophile was portrayed. But, you know, it wasn’t catnip to the studios and I didn’t expect it to be. That said, as a filmmaker who works outside of the studio system, that’s never to be taken quite so literally, because the financing of that movie was from October Films, a subsidiary of Universal. So it was Universal, a studio, that financed that movie. Of course, when they saw [it], the president of the studio said it was morally repugnant and wouldn’t allow it to be distributed by October Films.

DC: Other than that, he liked it. [audience laughs]

TS: And so what happened was they provided a loan to a company that was set up to distribute the film in the States, so that if the film became profitable, the studio that found it morally repugnant would at least make some money. The thing that all of you must know, of course, the only true morality that exists in Hollywood is if a movie is profitable it’s a moral film, and if it isn’t it’s not. I think what really drew me into this series of stories—certainly with the pedophile Bill Maplewood—I think I was looking for a character that could be most ostracized, most loathed, most feared, and it was kind of a test—in much the same way in some sense the way Abe Wertheimer in my current movie plays out—I put out that which is unacceptable, or that which is not likeable, let’s say, and then I try and see, not to [create sympathy] but to go and have the audience recognize a kind of test of the limitations of our sympathies; to what extent can we recognize the human in others. Because what makes him tragic, of course, is not that he’s a pedophile, but that he’s a great father who loves his son. Otherwise it would be only sordid. It was something, in fact, I wanted to even clarify further with Life During Wartime because oftentimes people said, “Oh, that movie Happiness shows pedophilia in a sympathetic light,” and that certainly wasn’t my intent, because if a pedophile had raped my child I would have no sympathy, it doesn’t make any sense. But I wanted to make clear that it’s about recognizing that he in fact is human, as painful as it is to recognize that. It’s a separate thing, the idea of sympathy. It’s probably my own sense of self-loathing. I don’t know that I felt that I had to create someone so horrific—you know, everyone would much rather die with Osama than Bill Maplewood.

TS: And so what happened was they provided a loan to a company that was set up to distribute the film in the States, so that if the film became profitable, the studio that found it morally repugnant would at least make some money. The thing that all of you must know, of course, the only true morality that exists in Hollywood is if a movie is profitable it’s a moral film, and if it isn’t it’s not. I think what really drew me into this series of stories—certainly with the pedophile Bill Maplewood—I think I was looking for a character that could be most ostracized, most loathed, most feared, and it was kind of a test—in much the same way in some sense the way Abe Wertheimer in my current movie plays out—I put out that which is unacceptable, or that which is not likeable, let’s say, and then I try and see, not to [create sympathy] but to go and have the audience recognize a kind of test of the limitations of our sympathies; to what extent can we recognize the human in others. Because what makes him tragic, of course, is not that he’s a pedophile, but that he’s a great father who loves his son. Otherwise it would be only sordid. It was something, in fact, I wanted to even clarify further with Life During Wartime because oftentimes people said, “Oh, that movie Happiness shows pedophilia in a sympathetic light,” and that certainly wasn’t my intent, because if a pedophile had raped my child I would have no sympathy, it doesn’t make any sense. But I wanted to make clear that it’s about recognizing that he in fact is human, as painful as it is to recognize that. It’s a separate thing, the idea of sympathy. It’s probably my own sense of self-loathing. I don’t know that I felt that I had to create someone so horrific—you know, everyone would much rather die with Osama than Bill Maplewood.

DC: In the hierarchies of evil, Osama would not be as evil as a pedophile.

TS: Oh, no, no. I think people could have a nice dinner and feel comfortable and digest just fine with Osama at the table. But, no, not if Bill Maplewood were there.

DC: When, in fact, people do dine with pedophiles and they don’t really know it.

TS: Exactly. It’s not like it’s a recent phenomenon. And it’s something also that the understanding in which it’s viewed shifts from culture to culture, just as all taboos do. The movie’s not interested… I didn’t even do any research on the subject. I probably had read a few things. Certainly nothing academic. It’s about making a leap. You invest yourself and imagine how would this person behave. How would this person live his life from moment to moment. What are those moments of agony and what is it that makes him not jump out the window.

TS: Exactly. It’s not like it’s a recent phenomenon. And it’s something also that the understanding in which it’s viewed shifts from culture to culture, just as all taboos do. The movie’s not interested… I didn’t even do any research on the subject. I probably had read a few things. Certainly nothing academic. It’s about making a leap. You invest yourself and imagine how would this person behave. How would this person live his life from moment to moment. What are those moments of agony and what is it that makes him not jump out the window.

DC: I could’ve asked you this off to the side, but the objects in your films, they always have a lot of significance. And I was just struck by the Humvee in this movie. Because, yes, people collect things, but as you and I have discussed before, their things collect them. Is it that this guy is such a jerk he buys a big car? It sorta goes with the sign on his room—“The Abester”—and he has like a fake bling necklace. And he had a Humvee, and he used it over and over.

TS: But the Humvee is like a toy car, you know? It looks like a little corgi. And it’s the kind of thing that just made sense for this character, who certainly doesn’t read articles on gas guzzling and environmentalism and so forth. Look, there are many people that drive these things. I’m not going to say they’re jerks, you know? There are so many people who drive all sorts of [bad ideas]. We all do. We all have our flaws and our weaknesses. We eat the wrong things and we buy the wrong things, but we’re all complicit in the corruption of living as Americans. It’s something we cannot escape. Or whatever nationality. And you always have to be complicit. Purity is a Nazi concept. It’s an Aryan concept. It’s not a human one.

DC: I think of you as a particularly American filmmaker in that regard. Certainly you have a common cause with some European filmmakers in terms of your ambitions. But all your movies are really American. I think it would have been a tragedy if October Films or whoever—whether you were trying to express some kind of F.U. to your success or not—[Happiness is] a deeply important film that had me on the sidewalk… I didn’t want to talk to anybody. I just wanted to try and assemble and piece it together myself. I think it’s always hilarious—I’m sorry for speech-making but we’re sort of wrapping up—is people are always complaining about movies that get tied up in a little bow. They’re always, “That was so pat,” and, “Oh, I saw that coming a mile away,” and then the minute you give them something else where the ending is ambiguous, they freak out. I didn’t know precisely how to feel about Abe, and to admit that I found something relatable and decent in the guy is to admit that that person exists in me as well, right? And so you’re sort of complicit.

When you think about the writing of a film, the finding people to back it, go out and shake the tin cup, and then actually get on set, which I’ve read you describe as significantly stressful to you, what’s the good part? What do you enjoy, and why do you continue to make films?

TS: It’s sort of like, why put pen to paper? It’s never exactly fun. I wouldn’t characterize it in that way. But I’ve been writing since I’m reading, and so there’s some part of me that has a need, which I don’t fully understand, to tell stories. And in some sense, every time you embark on a film, when you write the script I always think it’s genius, it’s perfect, and of course once I’m in the cutting room I’m chopping it up and realize how deluded I was when I went and embarked on production. But it’s a process of discovery, and self-discovery at that. What is this that I have wrought? What is this movie? It’s not quite what I thought it was—I mean, if I’m lucky it’ll turn out better—but, you know, every movie in some sense, as successful as it may end up being, it always fails on some levels as well. And that always lights some kind of match, like, “Next time I’ll get it right.” Next time, “I have the great story, I have the great thing.” And you have to in some sense have a great ego to think this way. Sensible people would know that they don’t really have it together. So it’s a tremendous gratification for me that I got to even make these movies. They mean something to me, and it’s very eye opening and gratifying to see that they mean something to others as well. People that I don’t know. People in foreign countries. It’s all that one dreams of when one is an aspiring filmmaker. So while the process is very stressful and it’s not fun, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have its gratifications.

Anonymous

Brilliant interview, left me with a lot to think about. That analysis of the Dollhouse scene was great, letting the audience subconsciously know what kind of world the movie’s in compared to blatantly telling you the world is cruel.