Nick Toti’s “Digital Gods”- Transmission Three

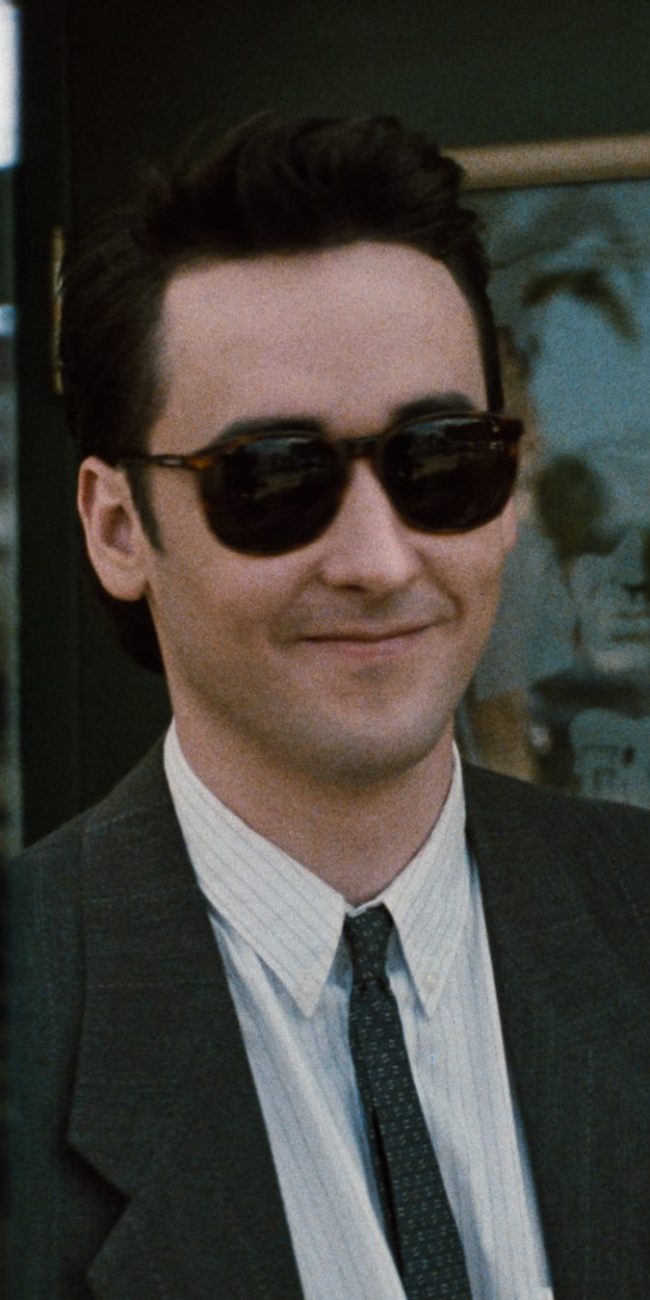

(In this follow-up to the last Digital Gods entry, Nick Toti interviews Zachary Oberzan about his life, his work, and the solemn meditative qualities of popular culture. Much like his movies, Oberzan’s answers range from the uncomfortably candid to the bizarre. Topics covered include: working in a cancer ward, asking favors of Abbas Kiarostami, fantasies about Miley Cyrus, and photos of diseased testicles.)

(In this follow-up to the last Digital Gods entry, Nick Toti interviews Zachary Oberzan about his life, his work, and the solemn meditative qualities of popular culture. Much like his movies, Oberzan’s answers range from the uncomfortably candid to the bizarre. Topics covered include: working in a cancer ward, asking favors of Abbas Kiarostami, fantasies about Miley Cyrus, and photos of diseased testicles.)

If you missed the last Digital Gods entry, I wrote an introduction to the work of Zachary Oberzan. The following interview was done as I was writing the piece, though I didn’t actually receive Zack’s answers until after the article had been written. If you aren’t already familiar with his work, I recommend starting with the article.

A quick note on the circumstances of this interview: Zack worked on answering these questions while dealing with some pretty intense familial obligations. He’s spent the past few years living in Europe, but is currently back in the US because his father is in poor health and is likely going to die soon. I only mention this because he had already given me this information and it is alluded to in the interview. He also answered some questions while visiting family in Maine and then others while in Kansas. He occasionally acknowledges these locations in his answers, so it can be a little disorienting.

While I’ve edited some for clarity, I’ve chosen to leave these somewhat confusing elements in place because I think that they reflect something of the spirit of Zack’s work. The shifting circumstances of his life tend to be crucial to his projects, so allowing a record of this sort to exist could prove telling down the line. It gets a bit dark and uncomfortable at points, but, as Frank Sinatra sings, that’s life!

THE INTERVIEW

Nick Toti: We’ve known each other for a couple years but I’m now realizing that there’s a lot that I don’t know about you. How would you describe your childhood?

Zachary Oberzan: A great deal of wonder and curiosity, and a great deal of abuse.

NT: Where did you grow up?

ZO: I grew up in the small town of Saco, Maine. That’s where Your brother. Remember? was filmed, both the old and new versions. I’m writing this now from that very house. I haven’t been back here in 5.5 years, with very good reason. But I seemed to have no choice.

NT: What is your relationship with your family like?

ZO: I have attempted to be non-judgmental for many years, under circumstances that would have caused most people to flee in horror several times over. But I’m afraid I have to be somewhat judgmental at this point, if I want to maintain what remains of my sanity.

**I am now writing this from Lawrence, KS, where I am watching my father quickly die. The upside to this is that I am re-connecting with the Oberzan side of my family after 30 years, and they are all much nicer and much saner people than the folks back in Maine.**

NT: How did you get into performing?

ZO: I blew what could have been a brilliant career in math & science. I was following that path quite assiduously into my teens. However, at age 13 I was distracted by Simon & Garfunkel. I fell completely in love with that music, as well as what was Paul’s current album at the time, “Graceland.” When Paul was 13 he wanted to be Elvis and when I was 13 I wanted to be Paul. So I began teaching myself how to sing and play guitar. Twenty-nine years later, I can almost pull it off. Then I started borrowing the VHS camcorder from the school library under the pretense of making educational work. But I was making short, violent films with my friends, and shooting scenes with my brother. Performing in these films led me to try out for the school play when I was 16. For better or worse, I was cast as the lead, and girls started to like me. That’s when it was over.

NT: You sometimes refer to your movies as “supplications” and, despite their humor or surface-level absurdity, they tend to feel somehow pious. Are you a religious person?

ZO: Oh, how I wish I was. What a rare, precious gift it must be, to believe there is Order. What a sigh of relief would escape my smiling lips, to know I do not have to create meaning–the meaning is already there! Ethnically speaking, I am a quarter Jewish, but I’ve never really practiced the religion. But I cling to that because of the camaraderie I project onto Leonard Cohen. And like Leonard, I explore Buddhism, and like Leonard, I’d say I’m a bad Buddhist.

Tell Me Love Is Real I refer to as a supplication because I am earnestly begging an answer to this question from the audience. For all the narrative web work, it’s actually that simple.

NT: Pop culture obviously plays a big part in your work. I assume that the decision to reference a movie/song/performer is largely intuitive, but I’m curious about how you think about these decisions. What is it that draws you to these specific things and makes you want to explore them in your work?

ZO: Let me offer you a larger explanation of how I work, which will cover this question and put it in context. Every new project is a diary entry of sorts. It’s about what’s going on in my life in the current moment. Many artists, to their credit, can choose an abstract topic, something they are interested in and want to explore through research, and construct a project around it. I can’t do that. I just don’t have the interest and am probably too lazy. Now, I’ve always had a large appetite and a larger memory for pop culture. As I begin to deconstruct my current life events, I begin to see parallels into pop culture, or occasionally classical culture, too. Coincidences begin appearing in numerous forms, and this is very key, because I would say the main ingredient in most of my work is Coincidence. In this haphazard, random, incomprehensible world we live in, it just tickles me and gives me a little thrill to find all these bizarre, amazing coincidences. All these random situations and events that somehow overlap. Perhaps it gives me the fugacious illusion that there is Order amidst the Chaos.

Every aspect of my shows has a “coincidence.” Nothing is stuck out there arbitrarily without a balancing weight. Often I discover those coincidences while working on the piece. If I don’t find a coincidence for some aspect, I’ll probably throw it out. None of this is research. I don’t care much for research, I’m overwhelmed already with everything that just slips in. For example, in 1996, I was staying in a tiny town near New Castle. A commercial for laundry detergent came on TV. It had kind of a muzak soundtrack. I fell in love with it – it was one of the most beautiful songs I ever heard. I tried to sing it for people to see if they knew it but no one did. About 15 years later I happened to listen to a Buddy Holly CD. There it was, “Words of Love” by Buddy Holly. That was the song I heard long ago in England. (The Beatles had a huge hit with it there.) Hence my subsequent obsession with Buddy. Point is, things like that happen to me with some frequency. And they become spiritual signposts. The projects then begin to coalesce around a central figure who remains a motif through the project, and becomes a personal hero, be it Jean-Claude Van Damme, Buddy Holly, or Elvis. As I currently watch my Dad die, I’ve been thinking a lot about Paul Newman.

NT: Your work always mixes theater and cinema. Flooding with Love for The Kid began as a live show called Rambo Solo; Your brother. Remember? and Tell Me Love Is Real were both theater pieces first (though they incorporated video elements); and now The Great Pretender seems constructed to be a movie that can only properly be seen with you as a live MC performing as Elvis and commenting on the action. What is it about the relationship between theater and cinema that keeps you engaged in this sort of medium-mingling?

ZO: Money. That’s the quick answer. I had made connections in the theater world as an actor, particularly in Europe, and realized that if I created my own work, I could make a living at this. Your brother. Remember? was initially intended to be a film, a follow up to Flooding. But I realized if I stuck some theater in there, maybe I could tour it and make some dough. This ultimately worked out for the best, as the overall piece was made much richer by the live aspects.

When Leonard Cohen made his first album in 1967, he figured, “I’ll make a little money, it will carry me for a year, and I’ll write a new novel.” He didn’t think he’d end up years later in hotel rooms late at night, trying to find the right chord for yet another song. But his first album was a hit, and presto, singing/songwriting became his main career. My first completely solo theater/film hybrid, YbR, was a hit, and the rest is history. Or silence.

NT: Flooding with Love for The Kid was your most popular movie. How do you account for its popularity?

ZO: Very easily. The combination of an extremely well known fictional figure (David Morrell, author of First Blood, would tell me later that there are only five literary characters that are internationally known: Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, James Bond, Harry Potter, and Rambo) and an innocent passion that ballooned into an unprecedented feat in filmmaking.

NT: In my opinion, Your brother. Remember? is one of the all-time great works of autobiographical nonfiction in cinema. Granted, this is not a hugely popular genre, but it has some heavy-hitters (Ross McElwee, Chris Marker, Agnès Varda, etc.). Were you influenced by any of these earlier works or consider its place as part of an already existing genre?

ZO: I didn’t really know it was a genre. I suppose the only history I had with the genre would be Kiarostami’s Close Up, which also jumps in time and uses reconstructions, but in a very different manner. That film had a profound effect on me when I saw it nearly 20 years ago, as we see later with TGP.

NT: Are there any particular filmmakers who have inspired your work?

ZO: Abbas Kiarostami of course. I learned a great deal from him, and am still learning. Other than he, I love the old Clint Eastwood movies directed by Sergio Leone and Don Siegal. Clint thanked both of them at the end of Unforgiven, because he learned directing from them. I think my violent action sequences owe something to these films, and the films Clint directed as well. I’m also a big fan of Stanley Kubrick, and early Scorsese films.

NT: The premise for Tell Me Love Is Real is, in part, that you and Whitney Houston overdosed on Xanax on the same night. However, this detail is never really mentioned anywhere other than in the synopsis and then only obliquely referred to in the movie itself. Did this event really happen? (Also, given the slippery approach to “truth” in that movie, does it matter if it really happened?)

***OK, now I am back in Maine writing.***

ZO: Your last question really summarizes a main theme in my work. “Does it matter if it really happened?” I am always tickled when I see a film advertised as “based on a true story.” That somehow entices people to watch it. But if a human can think it up, if a writer can write it, I assure you, at some point in human history that story happened. The clowns change, but the circus stays the same. So everything is a true story. As far as me and Whitney though, yeah, that really happened. More or less. That was the initial coincidence that kick started Tell Me Love Is Real.

NT: Having known you for a while now, I know that you’ve had other challenges related to your mental health. Given the personal nature of your work, I think this is useful information for viewers to have. Are you willing to share some of these experiences?

ZO: Well, TMLIR sums it up fairly well. For the particulars, people should watch that. I have very little if anything to hide. In brief, I have suffered from major depression and anxiety all my life. And then some post traumatic stress disorder, too. I am a connoisseur of international psych wards.

NT: There isn’t a lot of sex/romance in your work. This seems odd given that “love” is a recurring theme. I don’t have a specific question, but…what’s the deal?

ZO: I fuck so many beautiful women that by the time I have to work, I need a new subject. But seriously, folks, all of my songwriting is very sexual and romantic (sex and romance are very intertwined for me), and those songs find their way into my shows. And TMLIR actually does have a lot of sexual love mixed in there – Serge Gainsbourg described “J’Taime, Mon Non Plus,” as the Ultimate Love Song, and it’s about fucking. So it’s often there, just not so overt. Some of my early short films have some not-so-subtle sexuality in them. I would like to do a new piece about sex, especially if it involves me having it. With hot chicks.

NT: After Flooding with Love for The Kid, your next two movies moved away from conventional narrative. The Great Pretender is, in a way, a return to it. Do you have any thoughts on this or your approach to narrative conventions in general?

ZO: I don’t think in styles, so to speak, but rather, what is the best approach to tell this story? I am actually more of a traditional artist than I may appear, in that every work has at its core a narrative. I sometimes play with the structure of that narrative, because I find that structural changes enhance the story I want to tell. I could go off on a long tangent here about form versus content, but I don’t have time, I’m afraid.

Stay tuned for part 2 of Nick Toti’s interview with Zachary Oberzan…

Here are some links:

http://www.zacharyoberzan.com/

Watch Flooding with Love for The Kid: http://www.zacharyoberzan.com/flooding.html

Watch Your brother. Remember?: http://www.zacharyoberzan.com/ybr.html

Watch Tell Me Love Is Real: http://www.zacharyoberzan.com/tmlir.html