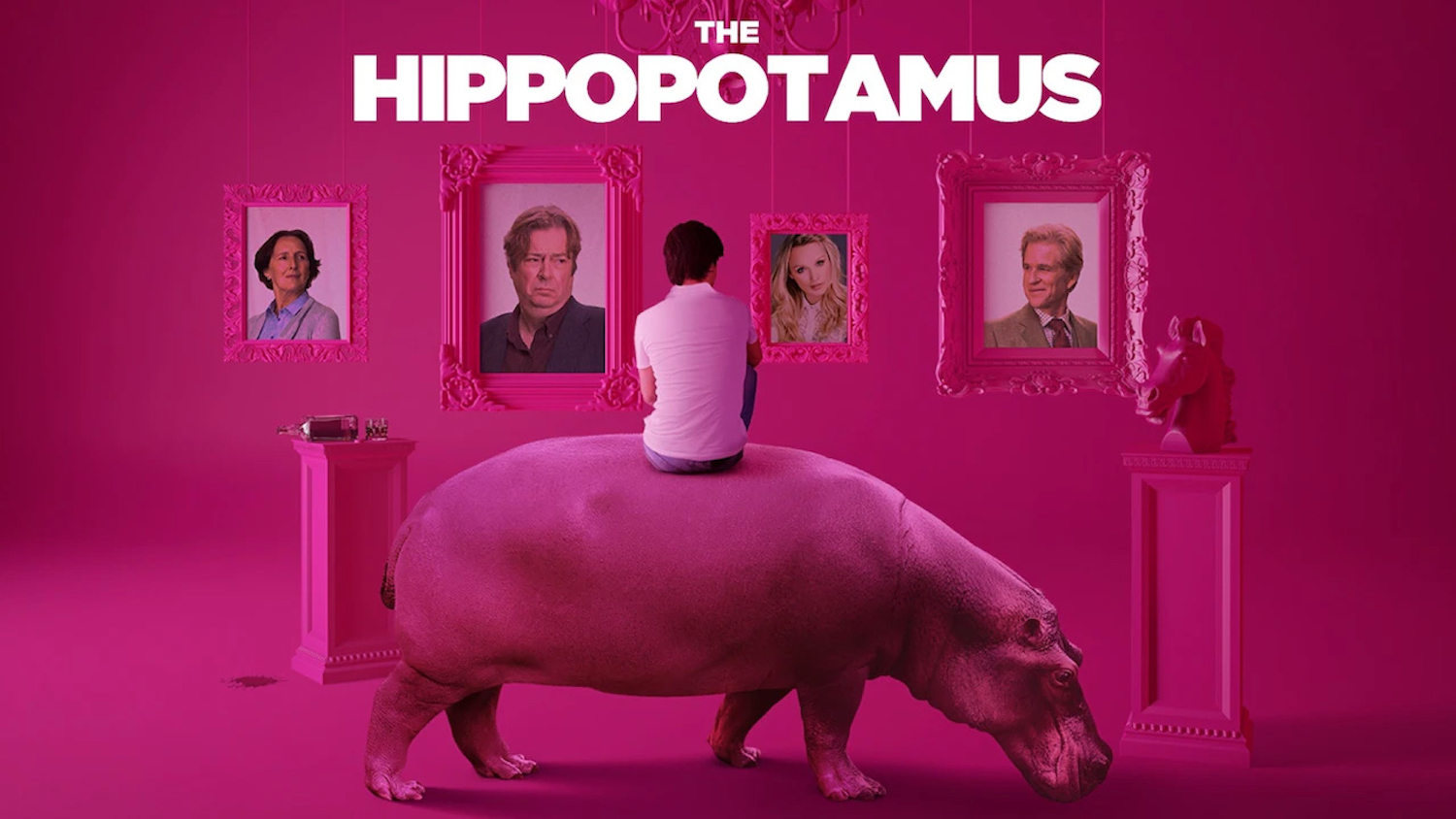

(The 43rd Annual Seattle International Film Festival starts May 18 and runs almost a month, all the way until June 11. Stay tuned to Hammer to Nail for reviews throughout the festivals monster run.)

The opening of John Jenck’s The Hippopotamus is a flawless, wordless introduction to the film’s protagonist, Ted Wallace. It starts with a close-up of a book baring a snippet of the identically titled poem by T.S. Eliot: “The broad-backed hippopotamus rests on his belly in the mud; although he seems firm to us, he is merely flesh and blood”. While the original poem is a metaphorical takedown of the Catholic Church, Ted Wallace, a lapsed poet and current theater critic, is a man who is skirting the edge of oblivion with his lifestyle.

The camera pulls out from the poem to reveal an unmade bed covered in books, an overturned lamp, and a full ashtray. A hand tosses a porn magazine atop the pile of intellectual vice. The camera cuts to a nearly empty whiskey bottle set on a brimming bookshelf. The hand snatches away the whiskey bottle, revealing a photograph of Wallace with his son and a postage stamp over the face of one who can only be his ex-wife. He pours the whiskey into a glass. He unbuttons his shirt, exposing a large, round belly. The camera cuts to a wide shot, as Wallace lowers himself into a claw foot bathtub of steaming water. He immerses himself, comes back up spouting water, and then brings the whiskey glass to his lips as the title appears. We already know so much about this man without the utterance of a single line of dialog. Once Wallace starts speaking, however, he never stops.

Not that it’s a bad thing. He’s a boor, yes. But he’s a boor with an incredible flair for language. In voiceover narration, he tells us that this former lauded poet hasn’t written a line of verse in three decades. Instead, he has been “turning whiskey into journalism” by reviewing local theater. Even when he’s belligerently berating the scantily clad cast of a production of “Titus Andronicus”, he’s a master at turning a phrase. The cast doesn’t appreciate his choice of words, however, the altercation leads to the end of his journalism career.

It makes sense that the protagonist of a film based on a novel by Stephen Fry would have a gift for gab. But Wallace is also deeply unhappy, and cannot stop himself from insulting everyone with whom he comes into contact. He’s a sort of high-functioning Ignatius J. Riley. His behavior is appalling, but you hang around to hear what he’ll say next.

Desperate for an income, and at the behest of his goddaughter, Wallace agrees to investigate some mysterious happenings at Swafford Hall – the country estate of an old friend (also his goddaughter’s uncle). The familial connection isn’t as important as the mystery itself. Jane, his goddaughter, was diagnosed with terminal leukemia until she paid a visit to the estate. Now she feels as if she’s been cured. But she wants to be sure.

Wallace is somewhat estranged from his friend, Michael (Matthew Modine). But not so from Michael’s son, David (Tommy Knight) – Wallace’s other godchild. (In Britain, people apparently accumulate godchildren like Angelina Jolie.) So Wallace arrives at Swafford Hall under the pretense of providing “spiritual guidance” to David. But really, he is receiving a princely sum from Jane to validate (or discredit) the miracles to which she attests.

You won’t be surprised to hear that Wallace is a staunch skeptic and, in fact, isn’t even entirely sure what he’s meant to look for at Swafford. But he occupies his time following David around and, of course, getting into the booze and upsetting people. Most of the joy of the film is the string of cunning vitriol that spouts forth from Wallace’s mouth. Played with aplomb by Roger Allam, Wallace physically resembles Stephen Fry, the author of the source novel. Perhaps The Hippopotamus was an outlet for Fry to let his shade flag fly. His biting prose and masterful turn-of-phrase translates nicely to screen. Tom Hodgson and Blanche McIntyre wrote the screenplay adaptation, which highlights such verbal gems as, “The notion hung about Swafford like a piss-filled Hindenberg”.

Tommy Knight gives an alluring performance as David, the talented young man at the center of the mystery, whose unusual circumstances afford him the opportunity to behave foolishly and wallow in a state of delusion.

The rest of the supporting characters are little more than targets of Wallace’s diatribes. That’s not to say that the A plot lacks appeal. But Wallace is, without a doubt, the star of the show. Come for son, stay for the shade.

– Jessica Baxter (@tehBaxter)