THE 53RD THESSALONIKI FILM FESTIVAL (2012)

History tears at the city of Thessaloniki, peeling away layers of time, creating a riot of temporality that is as staggering in its modernity as it is in its antiquity. Walk down any street and you’re sure to see the ground ripped open, exposing ancient stones organizing a different, lost city, while pale plastered apartment buildings hover above them, their empty balconies casting a shadow onto the crowded sidewalks below. The city is the crossroads of ancient empires, its foundational Macedonian identity shaped by invasion (Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman, Nazi, etc) and independence, disaster and triumph. Coming to a place like this, it is impossible not to feel the physical presence of the past, to see every modern action as existing in dialogue with time, each surge of emotion tempered by the overwhelming sensation that even the most evocative feeling exists as nothing more than a link in an infinitely long chain that holds everything here together.

Today, Greece is an explosion of purpose and struggle. Having joined the European Union, the nation finds itself suddenly beholden to a new set of masters. If Athens is at the heart of the battle against punishing political and economic reforms, Thessaloniki, a city of roughly 800,000 (it is the second largest city in Greece), is its young soul; mobilized by its enormous population of young people (I was told over 100,000-150,000 students inhabit the city), and pulled onto the streets by their passion as citizens, Thessaloniki does not rest. Demonstrations, strikes and public demands are a fundamental part of life in the city, with students pushing hard for reforms across the political spectrum. While the press I have read has described the protests as being against a new Euro-driven austerity, talking to people in Thessaloniki, it is clear that much more is at stake; these are not protests simply about the tough new measures being swallowed by the government, but a call for social reform that seeks to overhaul the way in which political life, with its traditions of nepotism and corruption, operates.

Today, Greece is an explosion of purpose and struggle. Having joined the European Union, the nation finds itself suddenly beholden to a new set of masters. If Athens is at the heart of the battle against punishing political and economic reforms, Thessaloniki, a city of roughly 800,000 (it is the second largest city in Greece), is its young soul; mobilized by its enormous population of young people (I was told over 100,000-150,000 students inhabit the city), and pulled onto the streets by their passion as citizens, Thessaloniki does not rest. Demonstrations, strikes and public demands are a fundamental part of life in the city, with students pushing hard for reforms across the political spectrum. While the press I have read has described the protests as being against a new Euro-driven austerity, talking to people in Thessaloniki, it is clear that much more is at stake; these are not protests simply about the tough new measures being swallowed by the government, but a call for social reform that seeks to overhaul the way in which political life, with its traditions of nepotism and corruption, operates.

When the 53rd Thessaloniki International Film Festival opened two weeks ago, it did so holding a unique place in this conversation between the political moment and the past. Having survived 53 years of upheaval and change, the festival is also facing its own dilemmas; funded in large part by public money (as so many European festivals are), the festival survives by walking the tightrope between a vibrant celebration of film and a vital cultural institution that is alert to the conflict at the heart of the community it serves. Nothing is too lavish (who would dare?), but the tenor of the event is just right, creating a mood that brings regional cinema (which includes Greek and, this year, Balkan film) into clear focus, situating new films both in a socially and historically relevant context.

This year saw the festival deftly offer tributes to Aki Kaurismaki, whose dark humor provided a poignant respite from the struggles on the streets, German (!!) filmmaker Andreas Dresen, Iranian auteur Bahman Ghobadi and Romania’s Cristian Mungiu, whose first film Occident (2002) won the festival’s audience award ten years ago and who returned triumphantly to anchor the festival’s Balkan Survey with a complete retrospective, including his new masterwork Beyond The Hills.

This year saw the festival deftly offer tributes to Aki Kaurismaki, whose dark humor provided a poignant respite from the struggles on the streets, German (!!) filmmaker Andreas Dresen, Iranian auteur Bahman Ghobadi and Romania’s Cristian Mungiu, whose first film Occident (2002) won the festival’s audience award ten years ago and who returned triumphantly to anchor the festival’s Balkan Survey with a complete retrospective, including his new masterwork Beyond The Hills.

The festival’s tributes surrounded an engaging program that gave voice to the region’s emerging filmmakers while, in the grand tradition of great European film festivals, simultaneously offering a more expansively international slate of competition films. While the new Greek cinema that has made it to onto American screens in recent years springs from young filmmakers like Yorgos Lanthimos and Athina Rachel Tsangari (whose new short The Capsule played at the festival), the festival gave an important platform to established Greek filmmakers like Ilias Yannakakis (Joy) and, most excitingly, Nikos Cornilios, whose 11 Meetings With My Father brought a social-realist perspective into a low-budget, independent filmmaking style that made the class dynamics of Greek society come alive.

Among the international films, the festival’s big winner was the celebrated A Hijacking from Denmark; the story of a Danish freighter taken by Somali pirates and the struggles of the sailors to stay alive while shipping company’s CEO personally negotiates their freedom, the film took home the Golden Alexander, the festival’s top juried prize. But perhaps the biggest winner was Amir Manor’s Epilogue, an Israeli film about an elderly couple named Hayuta and Berl, idealists who may not live to see their dreams of social change realized. Instead, the couple grow further detached from the world around them, retreating into one another’s arms. The film won four awards at the festival, across multiple juries and categories, and marked Manor as a filmmaker to watch. And of course, there were the American films, primarily low-budget indies, that stood shoulder to shoulder with their global contemporaries. Best among them were Jared Moshe’s independent western Dead Man’s Burden and Sean Baker’s moving Starlet which, nestled among the struggling protagonists of the European films, popped off the screen, a vision of hope and sunlight.

Among the international films, the festival’s big winner was the celebrated A Hijacking from Denmark; the story of a Danish freighter taken by Somali pirates and the struggles of the sailors to stay alive while shipping company’s CEO personally negotiates their freedom, the film took home the Golden Alexander, the festival’s top juried prize. But perhaps the biggest winner was Amir Manor’s Epilogue, an Israeli film about an elderly couple named Hayuta and Berl, idealists who may not live to see their dreams of social change realized. Instead, the couple grow further detached from the world around them, retreating into one another’s arms. The film won four awards at the festival, across multiple juries and categories, and marked Manor as a filmmaker to watch. And of course, there were the American films, primarily low-budget indies, that stood shoulder to shoulder with their global contemporaries. Best among them were Jared Moshe’s independent western Dead Man’s Burden and Sean Baker’s moving Starlet which, nestled among the struggling protagonists of the European films, popped off the screen, a vision of hope and sunlight.

For me, there was nothing so moving as the festival’s remembrance of the late Greek director Theo Angelopoulos, whose greatest films were shown in the festival’s Greek cinema program. Angelopoulos’ death in January was a devastating blow to cinephiles all over the world, and the festival paid significant homage to the greatest of all Greek filmmakers. I could have made no greater decision than to have my first film be Angelopoulos’ masterpiece O Thiassos (The Traveling Players) (1975), the story of a theater troupe making its way through the occupation of Greece during and after World War II. I was wholly unprepared for the film’s deep connection to the current political crisis, to the historical conflicts within Greek society; suddenly, like a lightening bolt, Angelopoulos‘ decision to blend time within his films, to offer no hard breaks between scenes but instead to have his characters contemporaneous in many time periods within a single shot, felt not only vital but mandatory. Sitting in a theater filled with students, each of them riveted to the screen, Angelopoulos’s film came alive for me in a completely new way; this was what it means to be Greek, the experience of time in the film the perfect distillation of the Greek condition. This was life among the ruins and the high rises, the eternal past and the inescapable present.

The festival offered another special salute to Angelopoulos; partnering with the Thessaloniki State Symphony Orchestra, they hosted an evening dedicated to the music of Angelopoulos’ films. In a packed concert hall on the eastern edge of the city, the orchestra, accompanied by the Greek jazz trio Human Touch and the incredible Greek singer Dimitra Galani, featured the work of composer Eleni Karaindrou, whose scores for Angelopoulos’ films were realized with staggering beauty (listen to one here).

The festival’s deep connection to Angelopoulos was capped with a change in the festival’s highest award, the Golden Alexander, which will now be given in honor of Angelopoulos. Angelopoulos’ widow and producer Phoebe Economopoulos gave a moving speech about this honor at the award ceremony, tying together the sense of loss and purpose that remained in the wake of the great director’s untimely death.

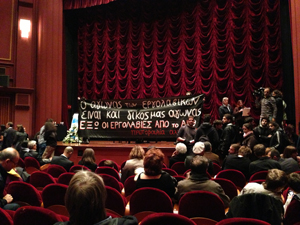

Of course, her words came after the start of the ceremony was delayed by students, who took over the stage and unfurled a huge banner demanding changes to the system of offering insider jobs to contractors at their film school. As the students peacefully assembled on the stage, the audience offered their support, cheering as the students’ demands were read aloud. It wasn’t the only time this happened. On the day the Greek Parliament was considering new reforms to contracts for public employees, the company contracted to produce live Greek and English subtitles for the festival’s screenings used the subtitle field just below the screen to let their own feelings be known. It read:

“Neaniko Plano Subtitles employees oppose the memorandum measures”

Each time the words appeared, at screening after screening, the entire theater erupted in applause. The cinema has never felt so alive.

— Tom Hall