Must-Sees At The 2014 New York Film Festival

Tonight’s kick-off of the 52nd New York Film Festival means that it’s time for our own annual tradition: celebrating this always mighty cine-event. Be sure to check back daily for updates to this page, as our crack staff are still making the trek to Lincoln Center daily for the ongoing press-and-industry screenings. This year, our core team consists of Tom Hall (newly minted Executive Director of the Montclair Film Festival), John Magary (writer/director of The Mend—i.e., one of the fiercest and most alive American motion pictures of 2014), Nelson Kim (filmmaker/teacher/hip-hop aficionado), and Mark Lukenbill (critic).

FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 26th ***OPENING NIGHT***

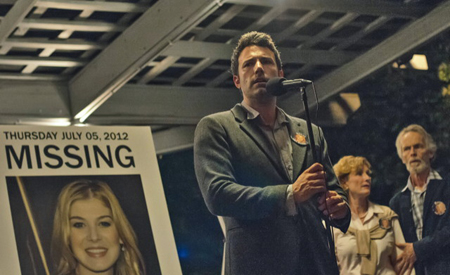

Gone Girl (USA, David Fincher, 145m, starting at 6pm there are *lots* of showings!) — Unseen by our team as of right ow, but it would be silly to assume that Fincher won’t deliver in some way, shape, or form.

Gone Girl (USA, David Fincher, 145m, starting at 6pm there are *lots* of showings!) — Unseen by our team as of right ow, but it would be silly to assume that Fincher won’t deliver in some way, shape, or form.

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 27th

Misunderstood (Italy/France, Asia Argento, 103m, 12pm) — The feature films of Asia Argento (Misunderstood is her third, and her first in ten years following The Heart is Deceitful Above All Things) are acidic and almost enthusiastically aggrieved; they’re portraits of narcissism and irredeemable acts, and include pointed jabs at the decency of the audience. If Misunderstood goes down any easier than her other films, it’s because it revolves around a 9-year-old girl, Aria, played by Giulia Salerno with a mop of androgynous hair and an endearing, wide-eyed expressiveness. Aria is constantly shuffled between her two feuding parents, her pianist mother (Charlotte Gainsbourg) and her movie star father (Gabriel Garko), and the film is segmented by sequences of the dejected, unwanted daughter carrying a suitcase and her beloved cat between the their separate houses. Elsewhere, her two sisters receive all of the attention, she’s ignored and belittled by her classmates and crush, and her best friend’s eye is straying towards less gloomy options.

Misunderstood (Italy/France, Asia Argento, 103m, 12pm) — The feature films of Asia Argento (Misunderstood is her third, and her first in ten years following The Heart is Deceitful Above All Things) are acidic and almost enthusiastically aggrieved; they’re portraits of narcissism and irredeemable acts, and include pointed jabs at the decency of the audience. If Misunderstood goes down any easier than her other films, it’s because it revolves around a 9-year-old girl, Aria, played by Giulia Salerno with a mop of androgynous hair and an endearing, wide-eyed expressiveness. Aria is constantly shuffled between her two feuding parents, her pianist mother (Charlotte Gainsbourg) and her movie star father (Gabriel Garko), and the film is segmented by sequences of the dejected, unwanted daughter carrying a suitcase and her beloved cat between the their separate houses. Elsewhere, her two sisters receive all of the attention, she’s ignored and belittled by her classmates and crush, and her best friend’s eye is straying towards less gloomy options.

Aria happens to share a legal, given name with the director of the film, and there’s no doubt that there’s some degree of autobiography happening here. This is Asia’s Somewhere, or a punk version of Fellini’s Amarcord; a 16mm, candy-colored testament to the affection Asia obviously feels for the perspective of childhood, if not the events that occur in it. The vignettes bleed together, each with differentiating, dazzling color palettes to reflect Aria’s emotional state, and the way Argento manages to integrate Aria’s imagination into the film feels fluid and natural rather than eye-rollingly twee. Aided by an outstanding soundtrack—a skill Argento perfected with her last film—and some inventive high-angle camera work, Misunderstood is most effective and sympathetic when it remembers to ditch the forlorn angst and be fun and funny (her delusional parents are total clowns, after all). While most of the film is a trigger warning wrapped in a time bomb, the perceptiveness with which Argento captures childhood with equal measures of nostalgia and cynicism make this one of the most brutally honest, viscerally relatable, and unshakable films about growing up in recent memory. (Mark Lukenbill)

Seymour: An Introduction (U.S.A., Ethan Hawke, 81 min, 12pm) — The art of teaching has long been a rich cinematic trope in the world of fictional adaptations—built upon the uplift of young people, the stories of great teachers bringing their students out of ignorance and into the light of knowledge have become almost mythological in their description of education as a process. Interesting then to see Ethan Hawke—star of one of the most beloved “educational uplift” films (Dead Poet’s Society)—make a non-fiction film that reverses the narrative and, in doing so, surpasses almost all of its cinematic predecessors.

Seymour: An Introduction (U.S.A., Ethan Hawke, 81 min, 12pm) — The art of teaching has long been a rich cinematic trope in the world of fictional adaptations—built upon the uplift of young people, the stories of great teachers bringing their students out of ignorance and into the light of knowledge have become almost mythological in their description of education as a process. Interesting then to see Ethan Hawke—star of one of the most beloved “educational uplift” films (Dead Poet’s Society)—make a non-fiction film that reverses the narrative and, in doing so, surpasses almost all of its cinematic predecessors.

Seymour: An Introduction is a portrait of the New York City pianist and teacher Seymour Bernstein, a gentle yet deeply rigorous champion of classical piano, musical interpretation, and the non-stop practice of becoming a true artist. After giving up a career as a concert pianist, Bernstein dedicated his life to teaching others, bringing his incredible gift of connecting deeply with the meaning and feeling of music as a true and independent language to students grappling with the challenges of becoming great performers. The film focuses not on a litany of students and their “becoming,” but on Bernstein himself as a teacher, beautifully encompassing his worldview and in doing so, reiterating the value of teaching as an end in and of itself, an opportunity to continue one’s own growth as a thinker and artist.

Hawke, for his part, uses the camera to convey maximum intimacy, framing Bernstein to perfection by isolating him in the frame or within the tight confines of his elegantly monkish studio apartment. Hawke also lets the music speak, imbuing the film with an audio framework of real beauty that leaves little doubt as to Bernstein’s gifts, before taking a few moments to play the student, asking Bernstein questions on camera that showcase the teacher’s ability to reduce big questions to simple, clear opportunities for self-examination. The result is an absolutely lovely portrait of an artist whose own deep belief in the practice of music making for its own sake is an inspiration to students, teachers, and lovers of music alike. (Tom Hall)

Goodbye to Language (France, Jean-Luc Godard, 70m, 9pm) — Of all the tricks left for our recessionary, limping-dog cinema—with its last-ditch struggles to fuse “immersion” with comfort, your living room with the movie house, to make lying back in a warm, reclining leather seat with chicken tenders and a phablet somehow comply with “falling in” to the “magic” of movies—3D still, somehow, carries with it a trace of possibility. Goodbye to Language, with its staggering abstractions and doublings, suggests the potential of 3D, before Jean-Luc Godard took it up, had been essentially unrealized. It was merely a layer, un-seen. After Godard, the layer has partially dissolved. He has rendered 3D confusing, lurid, supple, deep—he’s made it visible. A pixel-smudged poem with the rigor of a lab experiment, Goodbye to Language resists/questions/destroys interpretation, but it is also, to my mind, one of the most emotional statements of his six-decades-old, never-to-be-equaled career. Ingeniously, it calls attention throughout to the ophthalmological realities of the 3D process. I don’t exaggerate when I say I have never before felt so physically, painfully aware of my own eyes in a movie theater—indeed, during a now-infamous, howl-inducing trick shot, each eye, like a dissatisfied lover, actually strayed from the other. By transforming 3D into a tool not for immersion but participation, Godard has created a work of rapturous intimacy. We see with our own eyes, and with his. (John Magary)

Goodbye to Language (France, Jean-Luc Godard, 70m, 9pm) — Of all the tricks left for our recessionary, limping-dog cinema—with its last-ditch struggles to fuse “immersion” with comfort, your living room with the movie house, to make lying back in a warm, reclining leather seat with chicken tenders and a phablet somehow comply with “falling in” to the “magic” of movies—3D still, somehow, carries with it a trace of possibility. Goodbye to Language, with its staggering abstractions and doublings, suggests the potential of 3D, before Jean-Luc Godard took it up, had been essentially unrealized. It was merely a layer, un-seen. After Godard, the layer has partially dissolved. He has rendered 3D confusing, lurid, supple, deep—he’s made it visible. A pixel-smudged poem with the rigor of a lab experiment, Goodbye to Language resists/questions/destroys interpretation, but it is also, to my mind, one of the most emotional statements of his six-decades-old, never-to-be-equaled career. Ingeniously, it calls attention throughout to the ophthalmological realities of the 3D process. I don’t exaggerate when I say I have never before felt so physically, painfully aware of my own eyes in a movie theater—indeed, during a now-infamous, howl-inducing trick shot, each eye, like a dissatisfied lover, actually strayed from the other. By transforming 3D into a tool not for immersion but participation, Godard has created a work of rapturous intimacy. We see with our own eyes, and with his. (John Magary)

Maps to the Stars (Canada/Germany, David Cronenberg, 111m, 9pm) — Maps to the Stars is disquieting to the point of being off-putting, but probably not in the way you would expect from David Cronenberg. Those who go in expecting to be rattled by gruesome, visceral, “what the fuck” filmmaking will probably be disappointed; this is a movie that is curiously obsessed with its own inertness. The majority of the film is shot in static, blocked-off close-ups and the noticeable lack of any sort of sound design or ambiance leaves an oddly blank void of a canvas for the story to unfold upon. For a playful B-movie Hollywood satire, it surprising lacks the nightmarish visual stylings of Mulholland Dr., or the electrified kitsch of a De Palma film (it has more in common with The Canyons). But this isn’t the case of an auteur being asleep at the wheel; all of the above is done with the intention of making the film an empty vessel to deliver a bunch of wild, uninhibited performances, and the reason the lack of noticeable filmmaking is so unnerving is that a purely performance-driven film is becoming an increasingly rare thing.

Maps to the Stars (Canada/Germany, David Cronenberg, 111m, 9pm) — Maps to the Stars is disquieting to the point of being off-putting, but probably not in the way you would expect from David Cronenberg. Those who go in expecting to be rattled by gruesome, visceral, “what the fuck” filmmaking will probably be disappointed; this is a movie that is curiously obsessed with its own inertness. The majority of the film is shot in static, blocked-off close-ups and the noticeable lack of any sort of sound design or ambiance leaves an oddly blank void of a canvas for the story to unfold upon. For a playful B-movie Hollywood satire, it surprising lacks the nightmarish visual stylings of Mulholland Dr., or the electrified kitsch of a De Palma film (it has more in common with The Canyons). But this isn’t the case of an auteur being asleep at the wheel; all of the above is done with the intention of making the film an empty vessel to deliver a bunch of wild, uninhibited performances, and the reason the lack of noticeable filmmaking is so unnerving is that a purely performance-driven film is becoming an increasingly rare thing.

The intertwining stories introduce Julianne Moore is an aging actress obsessed with portraying a role made famous by her abusive mother—who occasionally appears as a ghost, played with effective menace by Sarah Gadon—and a power-hungry Hollywood family (John Cusack and Olivia Williams) with a sordid past and a child star as their main source of income. The arrival of Mia Wasikowska’s Agatha, a loopy, reptilian burn victim with a penchant for star worship, upends the lives of each of the characters. While everyone involved has an absurd amount of fun with their roles and turns in memorably unhinged performances, it’s Mia Wasikowska who elevates the film, finding odd idiosyncrasies in her character that prove, just as they do in all of her roles of the last few years, that she could probably write, act, and direct a scene better than anyone else in the room. (ML)

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 28th

Maps to the Stars (see above, 3pm)

Whiplash (USA, Damien Chazelle, 105m, 9pm) — Damien Chazelle’s first feature, 2010’s micro-budget black-and-white musical Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench, was endearing if slight: clearly the work of a promising talent, it was easy to admire and just as easy to forget. His follow-up, Whiplash, is a huge leap forward—a smart and serious drama, a rousing and rivetingly intense crowd-pleaser, and a virtuoso piece of filmmaking. Rising star Miles Teller plays Andrew, an aspiring jazz drummer who falls under the spell of Terence Fletcher (veteran character actor J.K. Simmons), a bandleader and conductor at Andrew’s conservatory. Fletcher believes it’s his mission to push gifted young musicians like Andrew to the limits of their endurance; that’s the only way to unlock whatever greatness may lie within them, even if it risks leaving them burned out or broken. Andrew submits to Fletcher’s merciless discipline until he begins to realize what it’s costing him, and turns against his mentor. Toward the end, the storytelling stumbles a bit in its rush to move things along, but all was forgiven by the climax of the thrilling musical showdown between student and teacher—I haven’t experienced that kind of surging excitement in a theater since 8 Mile’s final battle. (Nelson Kim)

Whiplash (USA, Damien Chazelle, 105m, 9pm) — Damien Chazelle’s first feature, 2010’s micro-budget black-and-white musical Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench, was endearing if slight: clearly the work of a promising talent, it was easy to admire and just as easy to forget. His follow-up, Whiplash, is a huge leap forward—a smart and serious drama, a rousing and rivetingly intense crowd-pleaser, and a virtuoso piece of filmmaking. Rising star Miles Teller plays Andrew, an aspiring jazz drummer who falls under the spell of Terence Fletcher (veteran character actor J.K. Simmons), a bandleader and conductor at Andrew’s conservatory. Fletcher believes it’s his mission to push gifted young musicians like Andrew to the limits of their endurance; that’s the only way to unlock whatever greatness may lie within them, even if it risks leaving them burned out or broken. Andrew submits to Fletcher’s merciless discipline until he begins to realize what it’s costing him, and turns against his mentor. Toward the end, the storytelling stumbles a bit in its rush to move things along, but all was forgiven by the climax of the thrilling musical showdown between student and teacher—I haven’t experienced that kind of surging excitement in a theater since 8 Mile’s final battle. (Nelson Kim)

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 29th

Whiplash (see above, 6pm)

Misunderstood (see above, 7pm)

Seymour: An Introduction (see above, 9pm)

TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 30th

The Look Of Silence (Denmark/Indonesia/Norway/Finland/United Kingdom, Joshua Oppenheimer, 98 min, 6pm) — In his heralded The Act Of Killing, Joshua Oppenheimer used his camera with a double-edged purpose, patiently, excruciatingly allowing former Indonesian death squad members to offer blow-by-blow details of their devastating crimes, while also creating formal, fictional spaces for their self-mythologizing to come to cinematic life. The effect was overwhelming for audiences and subjects alike, a brilliant conceit enriched by seeing his subjects’ deeply-held beliefs about the moral validity of their acts of murder shaken to their foundations in the film’s final moments.

The Look Of Silence (Denmark/Indonesia/Norway/Finland/United Kingdom, Joshua Oppenheimer, 98 min, 6pm) — In his heralded The Act Of Killing, Joshua Oppenheimer used his camera with a double-edged purpose, patiently, excruciatingly allowing former Indonesian death squad members to offer blow-by-blow details of their devastating crimes, while also creating formal, fictional spaces for their self-mythologizing to come to cinematic life. The effect was overwhelming for audiences and subjects alike, a brilliant conceit enriched by seeing his subjects’ deeply-held beliefs about the moral validity of their acts of murder shaken to their foundations in the film’s final moments.

In The Look Of Silence, Oppenheimer follows Adi, a small town optometrist as he pays visit to the men who killed his brother, checking their eyesight and, at last, confronting them about their roles in his brother’s death. As they obfuscate, threaten, and deny, the impossibility of justice becomes palpable and the decision to even broach the subject ennobled. Silence, a follow-up to The Act Of Killing, reverses the previous film’s perspective, showing the story of the state sanctioned violence through the experience of a family who lost a son and brother to a brutal act of political murder. In doing so, to my eyes anyway, Oppenheimer has made a superior film, one that combines the previous film’s dedication to exposing the scope of the culture’s assimilation of state terror with a direct need to find personal justice for those left behind. Whereas Act brought Indonesia’s mass graves into focus through the ironic detachment of the murderers—how could they? how is this possible?—Silence discards the distancing of cinematic conceits for a deeply empathetic, direct representation of victimization.

One of the disorienting effects of Oppenheimer’s work is his choice to immerse global audiences in a political and cultural history that may be deeply foreign to them without an ounce of didacticism. Instead, The Look Of Silence, like its predecessor, reaches for the experience of its subjects, both murderers and victims, for whom community is divided between the successful, who have been politically empowered and financially rewarded and for their roles in a political genocide, and the grieving, whose silence is assured by the deep social entrenchment of the murderers next door, down the road, and around the corner. The Look Of Silence is a devastating portrait of a nation unwilling to reconcile its crimes with those whose lives were shattered by them. (TH)

Hill of Freedom (South Korea, Hong Sang-soo, 66m, 6pm) — His detractors (those humorless philistines) complain that Hong Sang-soo keeps making the same movie with only slight variations. His admirers will be happy to learn that Hong has once again made the same movie with only slight variations. As usual, we get a comic dissection of male-female romantic entanglements served up with playful narrative trickery: Mori (Ryô Kase), a 30-something Japanese man, arrives in Seoul, where he hopes to rekindle an old affair, but discovers that his former lover is away on vacation; inevitably, he finds himself pulled into a new relationship with a waitress at a local café. The tale is recounted in a series of letters Mori writes to his ex, which she reads upon her return to Seoul, but—here’s the narrative trickery part—she drops the letters, scattering them out of order, so that she and we are forced to make sense of the events described by piecing them together in their proper chronology. All this is rendered in Hong’s characteristically unemphatic, blandly lit, long-take camera style, with its loping pans and lurching zooms—like late Buñuel, he somehow makes a virtue of his indifference to technique. But under the seemingly simplistic surface, there’s an ease and precision to the writing and directing that’s nothing short of masterly. One surprising new element appears in Hill of Freedom: as in many movies past, Hong gives us a long, awkward, and hilarious scene of drunken soul-baring and attempted seduction—only this time, it’s not soju or beer that sets it off, but (SPOILER ALERT) wine. Who knows where this bold departure will lead in the films to come? (NK)

Hill of Freedom (South Korea, Hong Sang-soo, 66m, 6pm) — His detractors (those humorless philistines) complain that Hong Sang-soo keeps making the same movie with only slight variations. His admirers will be happy to learn that Hong has once again made the same movie with only slight variations. As usual, we get a comic dissection of male-female romantic entanglements served up with playful narrative trickery: Mori (Ryô Kase), a 30-something Japanese man, arrives in Seoul, where he hopes to rekindle an old affair, but discovers that his former lover is away on vacation; inevitably, he finds himself pulled into a new relationship with a waitress at a local café. The tale is recounted in a series of letters Mori writes to his ex, which she reads upon her return to Seoul, but—here’s the narrative trickery part—she drops the letters, scattering them out of order, so that she and we are forced to make sense of the events described by piecing them together in their proper chronology. All this is rendered in Hong’s characteristically unemphatic, blandly lit, long-take camera style, with its loping pans and lurching zooms—like late Buñuel, he somehow makes a virtue of his indifference to technique. But under the seemingly simplistic surface, there’s an ease and precision to the writing and directing that’s nothing short of masterly. One surprising new element appears in Hill of Freedom: as in many movies past, Hong gives us a long, awkward, and hilarious scene of drunken soul-baring and attempted seduction—only this time, it’s not soju or beer that sets it off, but (SPOILER ALERT) wine. Who knows where this bold departure will lead in the films to come? (NK)

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 1st

The Look of Silence (see above, 9pm)

Goodbye to Language (see above, 9pm)

THURSDAY OCTOBER 2nd

Heaven Knows What (USA, Josh and Benny Safdie, 95m, 9pm) — As New York City has swollen with money and corporate homogeny under the Giuliani and Bloomberg mayoralties, demographic and economic shifts have not only restructured the physical landscape of the city, but forced the day-to-day struggles of its citizens onto the narrative margins. A metropolis that was once defined by its pockets of creativity and diverse vitality has become literally whitewashed, with lives led at the boundaries of polite society rendered invisible by the smiling, optimistic chokehold of privilege and convenience.

Heaven Knows What (USA, Josh and Benny Safdie, 95m, 9pm) — As New York City has swollen with money and corporate homogeny under the Giuliani and Bloomberg mayoralties, demographic and economic shifts have not only restructured the physical landscape of the city, but forced the day-to-day struggles of its citizens onto the narrative margins. A metropolis that was once defined by its pockets of creativity and diverse vitality has become literally whitewashed, with lives led at the boundaries of polite society rendered invisible by the smiling, optimistic chokehold of privilege and convenience.

The brothers Josh and Benny Safdie are two of a small, hopeful group of NYC-based filmmakers who have spent their time examining characters who operate beneath the gleam and glam of the city. In their new film Heaven Knows What, the Safdies have transformed the story of a real life street kid named Arielle Holmes (who dazzles playing Harley, a fictionalized version of herself) into a harrowing, ambitious film that feels alive to the experiences of the unseen world it inhabits. Harley’s life on the street is bookended by two terrible needs—the love of an abusive young death metal aficionado named Ilya (Caleb Landry Jones) and heroin, that most terrible of drugs, which turns Harley’s days and nights in to an ouroboros of suffering, hustling, pleasure and dependency.

Here again,the Safdies work with cinematographer Sean Price Williams, and once again, Williams’ work shines, with daringly visceral moments on the city’s streets captured intimately, yet at a distance, his long lens compositions bringing the viewer in close as an observer of lives hidden in plain sight. A special mention should also be made of Ronald Bronstein, who co-wrote the script with Josh and who edited the film with Benny; Bronstein’s gift for unflinching, urgent storytelling serves the material perfectly. With Holmes, the group has created a film that feels at once vital and watchable, a movie that describes the uncomfortable realities of the streets in a way that refuses to romanticize or glorify them. In a city that seems to have lost its interest in the effects of its own transfiguration, kudos to the New York Film Festival for showcasing this important film, and to the Safdies for showing us what otherwise might not be seen. (TH)

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 3rd

The Wonders (Italy/Switzerland/Germany, Alice Rohrwacher, 110m, 6pm) — Alice Rohrwacher’s Corpo Celeste was a very strong debut, a naturalistic coming-of-age tale with an impressive appetite for spiritual context. When it stumbled—say, when the cross imagery got a little heavy—it stumbled for admirable reasons. Like Corpo Celeste, Rohrwacher’s sophomore effort focuses on the toll that a suffocating family situation takes on adolescence, but the scope here is smaller, needier, almost threadbare. The first half of the film, in which 12-year-old Gelsomina (Maria Alexandra Lungu) endures the raw exhortations of her German beekeeper father Wolfgang (Sam Louwyck), has a somewhat familiar regional-arthouse libretto. At times, the quiet helplessness feels tasteful, even rote. But the second half, which finds Gelsomina’s family engaged in a campy local TV contest, opens the film up. A crucial, uncanny sequence deep in an Etruscan cave under candy-colored TV lights beautifully conveys the mysterious sweetness of regret. Rohrwacher’s editing rhythms are often so subtle that the narrative’s daring ellipses pass by in a kind of dreamy silence. This is no careful curation of experience; it’s a patchwork of memory. Time is lost at the very moment it’s savored. (JM)

The Wonders (Italy/Switzerland/Germany, Alice Rohrwacher, 110m, 6pm) — Alice Rohrwacher’s Corpo Celeste was a very strong debut, a naturalistic coming-of-age tale with an impressive appetite for spiritual context. When it stumbled—say, when the cross imagery got a little heavy—it stumbled for admirable reasons. Like Corpo Celeste, Rohrwacher’s sophomore effort focuses on the toll that a suffocating family situation takes on adolescence, but the scope here is smaller, needier, almost threadbare. The first half of the film, in which 12-year-old Gelsomina (Maria Alexandra Lungu) endures the raw exhortations of her German beekeeper father Wolfgang (Sam Louwyck), has a somewhat familiar regional-arthouse libretto. At times, the quiet helplessness feels tasteful, even rote. But the second half, which finds Gelsomina’s family engaged in a campy local TV contest, opens the film up. A crucial, uncanny sequence deep in an Etruscan cave under candy-colored TV lights beautifully conveys the mysterious sweetness of regret. Rohrwacher’s editing rhythms are often so subtle that the narrative’s daring ellipses pass by in a kind of dreamy silence. This is no careful curation of experience; it’s a patchwork of memory. Time is lost at the very moment it’s savored. (JM)

The Dragon is the Frame (“Projections Program 3,” USA, Mary Helena Clark, 15m, 7:15pm) — The Dragon is the Frame opens with a text scrawl that proclaims a declaration of “superficial vulgarity,” announcing an intention to “MAKE OTHERS SICK” through the striking decadence of personal fashion choices. While the text scrolls by, Star Wars style, a disembodied voice describes the unseen, hypothetical style icon who is ostensibly saying the words. The brash opening serves as less of a thesis and more a feeble call to combat what comes next: a montage of airless, haunting cityscapes plagued by noir lighting and murky textures, the crush of foot traffic audible just off-screen, like an advancing army. Occasionally there are images of a young man doing his best to heed the opening manifesto, refashioning his hair in a mirror and trying to seem confident in his image despite the fact that he’s surrounded by a crushing black void.

The Dragon is the Frame (“Projections Program 3,” USA, Mary Helena Clark, 15m, 7:15pm) — The Dragon is the Frame opens with a text scrawl that proclaims a declaration of “superficial vulgarity,” announcing an intention to “MAKE OTHERS SICK” through the striking decadence of personal fashion choices. While the text scrolls by, Star Wars style, a disembodied voice describes the unseen, hypothetical style icon who is ostensibly saying the words. The brash opening serves as less of a thesis and more a feeble call to combat what comes next: a montage of airless, haunting cityscapes plagued by noir lighting and murky textures, the crush of foot traffic audible just off-screen, like an advancing army. Occasionally there are images of a young man doing his best to heed the opening manifesto, refashioning his hair in a mirror and trying to seem confident in his image despite the fact that he’s surrounded by a crushing black void.

Despite the influence of Brakhage and Maya Deren, Mary Helena Clark makes films that are, in essence, narratives, but which operate on such a subdued, associative level of logic that it’s easy not to notice until you watch her films again, and again, preferably on a loop—her work is so hypnotic and seductively inscrutable that this is an easy spell to fall under.

Clark’s film plays beside new work from Two Years at Sea’s Ben Rivers and others in NYFF’s Projections series, a slate of exciting experimental films co-programmed by Basilica Hudson curator extraordinaire Aily Nash. While as a fan of Clark’s work her film jumped out at me, let this capsule serve as a metonymic reminder of the absurd spoil of riches within the series. (ML)

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 4th

The Wonders (see above, 3:15pm)

Inherent Vice (USA, Paul Thomas Anderson, 5:30pm, 5:45pm, 9pm, 9:15pm, 11:59pm) — This year’s centerpiece film was unseen by our eyes by post time but hopefully a full review will be dropping within the next few days!

Inherent Vice (USA, Paul Thomas Anderson, 5:30pm, 5:45pm, 9pm, 9:15pm, 11:59pm) — This year’s centerpiece film was unseen by our eyes by post time but hopefully a full review will be dropping within the next few days!

SUNDAY, OCTOBER 5th

Two Days, One Night (Belgium/France/Italy, Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardennes, 95m, 3pm) — Sandra (Marion Cotillard), a young wife and mother who works for a small company that manufactures solar panels, returns to her job after taking sick leave, only to learn that she’s been fired: at the foreman’s urging, her co-workers have voted to eliminate her position, in exchange for each of them receiving a significant bonus. Offered the chance to hold a new company-wide vote, Sandra has two days to visit each colleague and persuade them to change their minds.

The premise is just this side of forced, but this is a Dardenne brothers film, so Two Days, One Night sidesteps overt slickness in favor of documentary-inspired realism (long takes, hand-held camera) and an inquisitive humanism that embodies Jean Renoir’s famous aphorism, “Everyone has their reasons.” Which is not to say that Two Days, One Night isn’t as cunningly constructed as any Hollywood contraption. The Dardennes’ distinctive and much-imitated filmmaking style, with its focus on the patient observation of naturalistic behavior, sometimes obscures the fact that they’re traditional dramatists at heart: expert crafters of steel-trap story setups, corkscrewing plot twists, and what-happens-next narrative drive, all of which are on fine display here.

If the Dardennes have begun to move toward meeting the mainstream halfway—casting “name” actors like Cécile De France in 2011’s The Kid with a Bike and Cotillard here—they haven’t wavered in their commitment to depicting ordinary working-class lives; and, inseparable from that, their sharp sense of how material circumstances can press down like dark storm clouds, swallowing up everything in sight. Consider, again, the new film’s premise, which pits worker against worker in a cruel zero-sum game. Sandra and her colleagues are barely scraping by; the bonuses they’ll receive if she loses her job will pay for groceries, for children’s clothes, for much-needed home repairs. Some of the people who say no to Sandra have clearly agonized over the decision; some seem not to have given it, or her, a moment’s thought… The story ultimately leans more in the direction of hope than despair, but a menacing mood hangs over the entire proceedings. This is a world where things like love and friendship and solidarity still exist, but the threads are fraying, and everyone may only be one step away from losing it all. (NK)

National Gallery (USA/France, Frederick Wiseman, 180m, 4pm) — Frederick Wiseman’s new documentary takes us inside London’s venerable National Gallery, where over the course of three hours we’re witness to a dizzying array of activity. We sit in on marketing meetings where phrases like “profile-raising” get tossed around, we watch tour guides lecture on art to audiences young and old, and we listen as a conservationist describes the painstaking process of retouching a Rembrandt. The sense of deep immersion in process is everything: carving an ornate wooden frame, adjusting the lighting for a medieval-triptych display, hashing out an operating budget, rehearsing then filming a talk on Turner, and so many more. As he’s done in dozens of docs dating back nearly 50 years, Wiseman eschews voiceovers, titles, interviews, archival footage, music, and reenactments; this is fly-on-the-wall cinema—the eyes and hands of the filmmakers are selecting and shaping the material, but the aim is to come as close as possible to making us feel that we are part of the daily life of the institution being observed.

National Gallery (USA/France, Frederick Wiseman, 180m, 4pm) — Frederick Wiseman’s new documentary takes us inside London’s venerable National Gallery, where over the course of three hours we’re witness to a dizzying array of activity. We sit in on marketing meetings where phrases like “profile-raising” get tossed around, we watch tour guides lecture on art to audiences young and old, and we listen as a conservationist describes the painstaking process of retouching a Rembrandt. The sense of deep immersion in process is everything: carving an ornate wooden frame, adjusting the lighting for a medieval-triptych display, hashing out an operating budget, rehearsing then filming a talk on Turner, and so many more. As he’s done in dozens of docs dating back nearly 50 years, Wiseman eschews voiceovers, titles, interviews, archival footage, music, and reenactments; this is fly-on-the-wall cinema—the eyes and hands of the filmmakers are selecting and shaping the material, but the aim is to come as close as possible to making us feel that we are part of the daily life of the institution being observed.

Central to Wiseman’s method is that the movies rarely have anything like a strong narrative throughline or a central protagonist. Instead, the place itself is the protagonist. And like any good dramatic protagonist, the National Gallery has a goal, or rather a purpose: it exists to spark connections between the paintings and the people who come to look at them. That’s what ties together the efforts of the lecturers, the restorers, the curators and scholars, as well as the administrators and MBA types and even the air-kissing socialite benefactors glimpsed at an opening-night gala. Throughout the film, Wiseman transitions from one scene to another with nearly silent montages of museum-goers contemplating the canvases on the walls, as if to remind us that this is what all the work and all the busy-ness are for: to bring each of the Gallery’s millions of annual visitors into private communion with Leonardo, Rubens, Caravaggio, and the other dead greats. If you love paintings, if you enjoy learning about art or thinking about its place in the world, you’ll savor National Gallery—it’s a cinematic feast prepared by an 84-year-old master at the height of his powers. (NK)

Heaven Knows What (see above, 8pm)

Eden (France, Mia Hansen-Løve, 131m, 9pm) — The writer-director Mia Hansen-Løve is unique among modern filmmakers, a creator of epics driven by patient, careful intimacy. With Eden, her portrait of the French garage music scene of the 1990s, Hansen-Løve blends the idealism and innocence of her young dance music obsessives— sex and drugs, colored light and spinning vinyl— with the elegiac reality of the movement’s inevitable demise. There is no working director better suited to chronicling the end of this era than she, no one more capable of harnessing the hope and melancholy of youth as time washes it away.

Eden (France, Mia Hansen-Løve, 131m, 9pm) — The writer-director Mia Hansen-Løve is unique among modern filmmakers, a creator of epics driven by patient, careful intimacy. With Eden, her portrait of the French garage music scene of the 1990s, Hansen-Løve blends the idealism and innocence of her young dance music obsessives— sex and drugs, colored light and spinning vinyl— with the elegiac reality of the movement’s inevitable demise. There is no working director better suited to chronicling the end of this era than she, no one more capable of harnessing the hope and melancholy of youth as time washes it away.

Eden is the story of Paul (Félix de Givry), a lover of electronic dance music who decides to get his hands on some turntables and become a DJ. Working with his friend Stan (Hugo Conzelmann), the pair become fixtures on the scene, working raves, clubs and shows from Paris to Chicago (with a memorable stop in New York City). Along the way, hearts are broken, friends come, go, and pass away, drugs insinuate themselves, and real money is always just beyond their reach. And yet, the pair endure, even as the bubble of the scene shrinks around them, reality tightening itself like a constrictor around their hopes and dreams.

Hansen-Løve approaches this story (written with her brother Sven, a well-known DJ) from the inside out, creating scenes that refuse cliches like dance floor montages and triumphant breaks and drops in favor of a focus on the artists as flawed, creative people trying to stay in the game. If you’re looking for the cinephile/techno equivalent of a music-by-numbers Step Up film, you’ll want to search elsewhere. That said, it should be no surprise to anyone familiar with Hansen-Løve’s body of work that she continues to transcend by staying true to the human moments of the story with a rigorously controlled mise-en-scene that captures both the urgency and passion of her characters and the music they love. Eden is alive to the specificity of the scene it depicts, to character and story, but more importantly, to the reality that every moment is impossible to hold, another reluctant, fleeting step toward having to say goodbye to paradise. (TH)

MONDAY, OCTOBER 6th

Two Days, One Night (see above, 9pm)

TUESDAY, OCTOBER 7th

Eden (see above, 6pm)

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 8th

Hill of Freedom (see above, 9pm)

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 9th

Listen Up Philip (USA, Alex Ross Perry, 108m, 6pm) — Literary inspiration meets celluloid fury in Alex Ross Perry’s densest and richest work yet (sincere personal note of enthusiasm: ARP is the first HTN contributor to have a film in the NYFF main slate!). A scalding love letter to NYC, as well as a portrait of narcissism run amok, Listen Up Philip is as exhilaratingly grueling as cinema gets—and, yes, I mean that as a compliment. Jason Schwartzman and Elisabeth Moss are their usual sturdy selves, but it is Jonathan Pryce who delivers a toweringly assured performance as the Philip Roth-esque Ike Zimmerman. Perry’s screenplay, the top-notch performances of the cast, and Sean Price Williams’ gritty, bruisingly gorgeous Super-16mm cinematography combine to make for of 2014’s boldest new American films. (MT)

Listen Up Philip (USA, Alex Ross Perry, 108m, 6pm) — Literary inspiration meets celluloid fury in Alex Ross Perry’s densest and richest work yet (sincere personal note of enthusiasm: ARP is the first HTN contributor to have a film in the NYFF main slate!). A scalding love letter to NYC, as well as a portrait of narcissism run amok, Listen Up Philip is as exhilaratingly grueling as cinema gets—and, yes, I mean that as a compliment. Jason Schwartzman and Elisabeth Moss are their usual sturdy selves, but it is Jonathan Pryce who delivers a toweringly assured performance as the Philip Roth-esque Ike Zimmerman. Perry’s screenplay, the top-notch performances of the cast, and Sean Price Williams’ gritty, bruisingly gorgeous Super-16mm cinematography combine to make for of 2014’s boldest new American films. (MT)