Los Angeles Film Festival 2012 — A Preview

[Full disclosure: Paul Sbrizzi is an Associate Programmer at the LAFilmFest.]

The Los Angeles Film Festival fulfills multiple missions. It opens a window onto the front lines of the international film scene, giving selections from Sundance, Berlin, Rotterdam and such their first L.A. screenings. Its narrative competition is a premiere showcase for young, mostly American indie talent. It also has a pretty clear progressive political agenda, both in its selection of socio-political themed documentaries and in its commitment to diversity: this year, in addition to the usual wide selection of Mexican and South and Central American films, there’s an emphasis on Afro-Film, with some remarkable work. Here are some of my top picks.

DOCUMENTARIES

If there’s a unifying theme to the 2012 lineup it’s something to do with the hope and determination that subsist in a time when faceless and uncaring forces seem to work tirelessly to push mankind into various forms of slavery. There are a lot of intense watches this year, but right at the top of the list has got to be Call Me Kuchu by Katherine Fairfax Wright & Malika Zouhali-Worrall, which dives headfirst into the struggle for the most basic of human rights by LGBT activists in Uganda. The filmmakers come up with clear evidence of the influence exerted by American right-wing so-called Christians on local politics, and the use of demagoguery to get homosexuality codified as a capital offense. It’s a haunting, unforgettable film that takes you into the daily existence of people willing to risk their lives in order to be who they are openly. It’s also a great exposé, showing how far American far-right groups are willing to take their agenda when given the opportunity.

There’s a different flavor of horror in Lauren Greenfield’s Queen of Versailles, about timeshare tycoon David Siegel and his wife Jackie, who suffer a cataclysmic reversal of fortune at the time of the 2008 economic collapse. Their 90,000 square foot dream mansion, which is modeled after Versailles—the Versailles in Las Vegas, not the one in France—is left half-finished and their lifestyle curdles into a grotesque and decaying version of what it was. If the film occasionally strays into “Real Housewives” territory, it’s nonetheless an always-fascinating slo-mo train wreck with no shortage of rich imagery: Jackie on a budget coming out of Walmart pushing massive, overflowing shopping carts of cheap crap; an exotic reptile found dead from neglect because the servants have been fired; David’s horror when Jackie comes home from a plastic surgery procedure that’s left her face swollen, discolored and bloody. The Siegels are willing to let it all hang out through the good times and the bad. Greenfield’s film also documents the predatory greed of banks during the economic crisis—happy to drive a business like David’s into ruin in order to gobble up its valuable assets.

One of the stars of the festival will likely be Ina Mae Gaskin, the main subject of Sara Lamm and Mary Wigmore’s Birth Story: Ina May Gaskin And The Farm Midwives, who changed an entire generation’s attitude toward childbirth when she took up midwifery on a Tennessee hippie commune in the 1970s. She became a crusader against unnecessary C-sections, writing books and making personal appearances, displaying a staggering depth of knowledge and a raunchy sense of humor (“Men think they’re the only ones whose stuff can get big and then get small again”). It’s a wild ride, with graphic footage of births—mothers screaming in pain as gooey, purple creatures emerge like aliens from bushy vaginas, then quickly become pink bundles of cuteness. And there’s a remarkable contrast between simple, earthy ‘70s childbirth and the contemporary version: a don’t-touch-me-I-can-do-it-myself water birth in a pricey-looking drawing room, with a hired cello player for an extra dash of luxury.

The basic filmmaking craft in Kirby Dick’s The Invisible War leaves something to be desired, but in the end it’s an important, infuriating film about a fundamental structural flaw within the U.S. military that allows almost all incidents of rape to go unpunished. Women who report being raped are in fact frequently charged with spurious offenses themselves and eventually almost always discharged. And if that’s not enough to convince you how f**ked we are as a country, check out Eugene Jarecki’s The House I Live In, which won the Grand Jury Prize for Best Documentary at Sundance earlier this year—it’s a look at the horrendous human toll of the so-called War on Drugs, with a pointed take on how anti-drug propaganda through the years has been a way of marginalizing and oppressing targeted populations. The film specifically examines the huge disparity in sentencing laws between crack cocaine, which is more common in inner-city black communities, and powder cocaine, more commonly used by suburban whites.

And yet and yet—Frieda Mock’s G-DOG is powerful evidence that one person can make a huge difference in the world. It follows Father Greg Boyle, a Jesuit priest who runs Homeboy Industries, a program in downtown Los Angeles that trains and rehabilitates young felons being released from prison, giving hope to a population that society has given up on. The film highlights Father G’s patience, humor and determination as he struggles to find funding to stay in business.

This year’s LAFilmFest program features several outstanding films from Mexico’s thriving documentary scene. Canícula by José Álvarez transports you into the dreamlike existence of the Totonac people from the state of Veracruz, who seem to still be living in pre-Columbian times, gathering clay to make their characteristic pottery and training their young men to “fly” in a religious ritual.

I have to admit that sitting through a film called Drought was something I kept putting off, but Everardo Gonzalez’s film turned out to be a stunner. In a small community in Coahuila, northeastern Mexico, the people work from dawn till dusk on their semi-arid land. A census worker is informed by a bemused woman that no, her family has no radio, much less a TV or a refrigerator or a car—they own nothing but a mule-drawn cart. They get their water from a distant basin that’s slowly drying up. In spite or maybe because of this, these people appear to be perpetually in good cheer. They seem to inhabit their right place within nature’s majesty and connect to the spirit that animates it. Their world is captured with alchemy by Gonzalez’s lens, and composed into an exquisite, shifting symphony of image and sound.

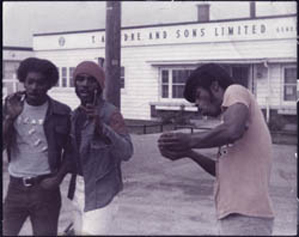

A documentary about the rediscovery of a forgotten proto-punk group named Death didn’t seem likely to reduce me to tears, but Mark Christopher Covino and Jeff Howlett’s A Band Called Death is the story of a kind of miracle. The Hackney brothers, three African-American teenagers from Detroit, start a band in the early 70s, inspired by The Who and Alice Cooper, and come up with something that sounds a lot like what would later be called punk. The natural charisma of leader David Hackney gets them an opportunity to record an album, but he refuses to change the band’s name to something more appropriate to the mellow-groovy times; the record is never released and the band is completely forgotten. A Band Called Death paints David as a visionary who never gives up his belief in the project: shortly before he dies in 2000 he gives the master tapes to his brother, assuring him that the world will come looking for them. When a rare copy of a self-released Death single finds its way into the hands of a serious record collector, it sets the wheels in motion for a full-scale re-discovery of the band, and that’s when this reviewer found himself repeatedly losing his sh*t.

Another film I found genuinely moving was Bernardo Ruiz’s Reportero, which traces the history of the Tijuana tabloid Zeta and its reporters’ heroic commitment to taking on the druglords and their accomplices within the police force, the military and the government. So heartening to see that even in the midst of some of the worst corruption anywhere there are people willing to risk their lives to speak the truth. Similarly, Mai Iskander’s Words of Witness takes you into the thick of the action during the pivotal days of the 2011 revolution in Egypt, through the eyes of Heba Afify, a young woman reporter. Much of the film’s focus is on Heba’s arguments with her mother, who supports the revolution but is terrified of the personal risks her daughter is taking. The jerky footage of activists storming the national security headquarters is action-film thrilling; the evidence of the government purposely inciting divisions between Christians and Muslims is fundamental to an understanding of what’s happening in the country politically.

Some of the most emotionally riveting footage in the festival is in Without Gorky, directed by Cosima Spender, the artist’s granddaughter. Gorky’s widow Agnes Magruder (known as Magouch to her family), now 91, shares the raw details of their marriage and his tragic final years; she bravely relives the experience of knowing he was planning to commit suicide and feeling to some extent responsible—but powerless to stop him.

A light dessert after all that weighty fare is About Face by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders—a carousel of interviews with top fashion models from the recent and distant past. Jerry Hall is still a one-woman party, totally adorable with her Texas drawl and mane of don’t-give-a-f**k damaged hair; Isabella Rossellini is elegantly mannish and hella smart, getting all philosophical about beauty and aging; Christy Turlington hasn’t aged a nano-second since 1992. But the star of the film is Carmen Dell’Orefice, 80 years old and stunning with her striking head of white hair. Asked about plastic surgery, she delivers a line for the ages: “If you had a ceiling fall down in your living room wouldn’t you get it repaired?”

NARRATIVES

Amidst a lot of solid offerings there were three films that stood out as the kind of powerfully individual works that peel out of your driveway to take you on a ride to delightful and dangerous places.

Terence Nance’s An Oversimplification of Her Beauty, which premiered earlier this year at Sundance, performs a kaleidoscope of formal experiments to tell an elliptical love/not-love story. A recurring, educational-type voiceover analyzes what it considers empirical facts about the filmmaker’s failures in his romantic pursuits generally (largely having to do with his cool and stoic persona), and in his quasi-relationship with the smart, talented and charming Namik specifically. Nance creates a visual counterpoint to the words of the superego with live-action and animated scenes that seem to spring from the id. If this sounds cute or pretentious it’s not. It’s both playful and profound, and the gorgeous animated sequences flow like the rivers of the mind. This film hit me again and again with beautifully verbalized summations of scattered intuitions of my own. Terence’s eventual love letter and Namik’s response are pure molten gold.

Olmo Omerzu’s A Night Too Young, an official selection of this year’s Berlinale, is a rich stew of emotional entanglements bubbling through a New Year’s Day and night in the Czech Republic. What’s unique about it is what isn’t explained: Omerzu opens on a shot of the inside of a dark house catching fire, then drops the viewer in the middle of a heightened dramatic situation—some kind of love triangle. The use of negative narrative space throws you nicely off balance, shifting your appreciation of the film to engage fresh and eager exurbs of the mind. Omerzu adds further sculptural dimensions by adding a couple of pre-teen boys—and then a horny cop—to bounce the central story off of.

Neighboring Sounds, which won the FIPRESCI award in Rotterdam, is a hugely ambitious work by an important new voice in film, Brazilian director Kleber Mendonça Filho. It’s the story of a group of upper middle class neighbors in the city of Recife gradually losing control of the street they live on, after hiring a working-class security enterprise with murky intentions. Mendonça Filho composes his scenes like pieces of music, with unexpected camera movements adding stabs of hyperreality; a variety of encroaching sounds gradually exacerbate the characters’ melancholic sense of dread. Maeve Jinkins is quietly spectacular as Bia, a young pothead mom—she rides the sweet spot between deadpan comedy, horror and madness.

There are also a number of interesting lean-budget American indies in the lineup.

Todd Berger’s It’s a Disaster is a kind of Gilligan’s Island turned outside in, with a group of L.A. Eastside-hip-young-coupled-entertainment-industry types stranded inside a Craftsman trophy house during a nuclear disaster. Like in the ‘60s sitcom, the humor comes from the characters’ inability, even when the stakes are life-and-death, to see outside their hilariously limited world-view.

Gayby is the feature version of Jonathan Lisecki’s much-awarded short film: gay Matt and straight Jenn return to expand their story of no-turkey-baster-needed mitosis and meiosis. The rainbow-sweet narrative is cut with pleasingly bitter observations of dating rituals in the big city. Jenn Harris’s vertical-sex orgasm is comedy hall of fame stuff, and Lisecki himself, in a supporting role, brings the gay like no one else—cf. his three-syllable pronunciation of the word “brunch.”

Toddler improv is an idea whose time has come. There’s a certain amount of scripted story to Cory McAbee’s Crazy and Thief, but in the end it’s just a bit of structure on which to hang the beauteous bursts of freeform poetry from McAbee’s two-year-old son John Huck, set up by his seven-year-old sister Willa Vy. The final shot is pure hell-bound nihilism that will mess with your head; it left me with extremely mixed feelings and a lot of fodder for discussion.

Alex Karpovsky’s Red Flag is a loose, seemingly autobiographical chronicle of the director’s well-intentioned but disastrous attempts to deal with his inability to commit to his long-time girlfriend. The occasional shot would have benefited from another take, but Red Flag has the exciting feel of grab-and-go filmmaking. Karpovksy is a strong lead, with an impressive willingness to make himself look like a fool; he gets fantastic comedic performances from Jennifer Prediger as his stalker and Onur Tukel as the excitable buddy that tags along for the road-movie ride.

There are some other really great performances that deserve a special mention. John McInerny, a real-life Argentinian Elvis impersonator in his first acting role, looks a mess in Armando Bo’s The Last Elvis: overweight and with badly thinning shaggy hair, he’s perfect. But he also brings a childlike, solipsistic madness to the part that elevates the whole film, and his singing voice is sweet, powerful, and dripping with feeling. Soufia Issami is a force as Badia in Leila Kilani’s On the Edge, playing a Moroccan shrimp factory worker determined to do whatever it takes to get the stink off of her skin and make the leap to a higher rung of society. In David Fenster’s Pincus, Dietmar Franusch brings to life an archetypal character for our times—also named Dietmar (as is the custom in contemporary indiefilmland): a middle-aged German master builder living on no money in a tent, picking up the occasional bit of work, philosophizing, smoking a lot of weed. He cuts through the doubts and pretense of the film’s other characters by just being beautifully genuine and human. And Kacey Mottet Klein—playing a 12-year-old boy who steals gear from tourists at a Swiss ski resort to support himself and his unstable older sibling in Ursula Meier’s Sister—is a revelation, showing crazy confidence and range for his age.

— Paul Sbrizzi

[For more detailed information about screening dates and times, go here.]

Midwife in Lasvegas

In Los Angeles most of the lady are

midwifes and they are not well educated but they have experience. They don’t get

experience from any center they themselves tried and give birth to a baby to

different pregnant ladies and they get experience.