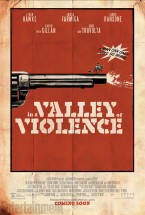

IN A VALLEY OF VIOLENCE

(The 2016 SXSW Film Festival kicked off March 11 and runs all the way until the 19th. We have boots on the ground and reviews coming in by the truckload so stay tuned to HtN throughout the fest!)

I attended a late night screening of The Hateful Eight in 70mm a few days after Christmas. The theater was not crowded but I kept turning around in my seat to see if the genre parody was working for people, because it certainly was not for me. I am a big Western fan and I can appreciate Tarantino as an ersatz film DJ but The Hateful Eight seemed like some sort of mash up of Agatha Christie meets operetta bad dinner theater. None of the characters had any depth and they seemed to have absolutely no grounding in anything except as a vehicle to present semi-clever dialogue. The experience of watching the new Ti West film, In A Valley of Violence, at the Stateside theater in Austin for SXSW was completely different in that, despite the melding of different tones, it felt seamless. Most importantly, it was thrilling, fun and smart. Not an easy thing for a genre film to accomplish.

One of the most difficult aspects of the director’s job is the management of tone. It’s not something you can really teach and is, in some ways, instinctual. Yet the mastery of tone is absolutely essential within genre films that are playing to today’s audiences who are actually quite sophisticated in their self-awareness of genre codes and tendencies. In terms of technical skill it’s actually far more challenging to direct an intelligent genre film than it is to direct a straight naturalistic character drama.

In A Valley of Violence is poised somewhere between an Italian Spaghetti Western tone circa say Duck You Sucka and the mid-fifties serious overwrought psychological westerns like Nick Ray’s Johnny Guitar and Fuller’s Forty Guns. The film is full of surprises yet it still feels familiar and grounded and respectful of the tradition in which it’s working. A true genre master is not someone who is trying to flip the whole playbook, it’s someone who can find his own point of view within that playbook. Any jazz musician can take a jazz standard like Body and Soul and mess it up with dissonance and kookiness, or layer on a guitar or zither; the challenge is in playing that standard in a way that respects it yet makes it sound like you’ve never heard it before. That’s what Charles Mingus, Sonny Stitt, Miles Davis, and Sonny Rollins did and it’s what we have here with Ti West’s second non-horror film.

The film starts with a fantastic credit sequence that comes straight from the Spaghetti Western playbook. Silhouettes of our hero on a horse and his trusty sidekick, a scruffy dog who was introduced in the pre-credit sequence as a feisty guard dog, while the Jeff Grace soundtrack evokes and simultaneously harkens back to the era’s best Morriconne. It’s a credit sequence that is visually striking and sets the tone perfectly.

Ethan Hawke plays Paul, the lonely High Plains Drifter who is running from his own war induced grief and guilt. He rides into the nearly abandoned dusty town of Denton, trusty dog by his side, where a young blowhard (James Ransone) holds court like a mad, hateful, Republican politician. His henchmen are colorfully played by Larry Fessenden with a crazed twinkle in his eye, the steely sober Toby Huss and the “Tubby” bumbler played by Tommy Nohilly. The first bar room confrontation between the loudmouth and our Drifter ends with one punch as Ransone is dropped cold. Paul goes into the hotel to get a bath and meets the winsome Taissa Farmiga, who pledges her allegiance to him if he tries to clean up the town. Paul doesn’t want to be bothered and on his way out he’s confronted in the lobby by a low-key-yet-scary patriarch played by John Travolta, seated with a cane and a leg brace. Travolta both apologizes for his idiot son and lets him know it won’t end well if he sticks around. Hawke heads for the hills.

The set up is classic and familiar and the second act starts with a brutal act of violence that clearly establishes our hero’s justification for revenge. That urge for revenge doesn’t really get questioned on say, the existential level of Clint’s Unforgiven, but it allows West to describe his view of a world in which man is inevitably possessed and then consumed by the ultimately destructive urge to control and dominate.

In a Valley of Violence is a visual treat that is both smart and fun and is a great western for an election year. Catch it on the big screen for full impact.

– Mike S. Ryan