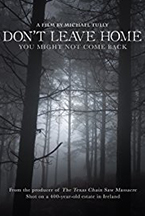

DON’T LEAVE HOME

(The 2018 SXSW Film Festival kicked off March 9 and ran all the way through to March 17. Hammer to Nail has a slew of reviews and interviews coming in hot and heavy so keep your dial tuned to HtN!)

**Editor’s note: Don’t Leave Home writer/director Michael Tully is a founding editor of Hammer to Nail and a friend of the site. While Michael is no longer an editor at HtN, we feel any hint of a conflict of interest should be clarified to our readers.

The prologue of Michael Tully’s Don’t Leave Home sets things up in the Academy ratio, like a lost film by a classic Western European master (Eric Rohmer, Robert Bresson, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger are the first to come to mind). The color palate, framing, camera movement, and editing give the allusion of 1950s and early 1960s cinema. The lack of dialogue allows us to luxuriate in the moody Irish Gothic imagery, while the prologue presents the religious and supernatural themes that become the backbone of Tully’s film.

When the film switches to modern times, the aspect ratio expands to a widescreen format. We are transported to the United States, where Melanie Thomas (Anna Margaret Hollyman) is preparing for an art opening that will showcase her small-scale dioramas of unsolved missing person cases in Ireland. The keystone of the exhibit is a diorama of the disappearance of Siobhan (Alisha Weir), the “evil miracle” we witnessed in the prologue.

After receiving a devastatingly negative early review of her upcoming opening, Melanie becomes seriously concerned about her financial situation. Melanie receives a mysterious phone call on behalf of Father Alistair Burke (Lalor Roddy) inviting her to visit the exiled priest who was the primary suspect in the Siobhan case, with promises of buying of one of her dioramas and a providing a hefty commission for a new one. With no other option than to accept the invitation, Melanie rationalizes her decision by convincing herself that Father Burke must be innocent. How could a Catholic priest ever do anything wrong, especially to a child?

So, yeah, Melanie decides to travel to a foreign country to stay with a reclusive ex-priest who was the prime suspect in a missing child case. Upon Melanie’s arrival in Ireland, it immediately seems as though she has entered a horror film – somewhat reminiscent of Suspiria when Suzy Bannon (Jessica Harper) first arrives in Germany. The adroit tonal shift occurs when an apparently mute chauffeur (David McSavage), a genetic crossbreed of Lurch and Uncle Fester, is the first person Melanie meets. Not much later, Melanie has a vision that she is watching herself from an upstairs window of Father Burke’s menacingly gothic, 300-year-old home. Then, Melanie naively abides by the directive of Shelly (Helena Bereen), Father Burke’s caretaker of questionable trustworthiness, to venture alone down a creepy path to visit a local grotto of the Virgin Mary.

While at first we might chalk Melanie’s questionable judgment up to jet lag, she continues to make poor decisions that could put her at risk. Seemingly blinded by her desperation to make money and get her career back on track, Melanie is unable to recognize the multitude of clues that she is probably not safe. Nightmares, visions, and scary noises trigger her curiosity, rather than freeze her with fear or make her question her next move. Then again, Don’t Leave Home wouldn’t be much of a horror film if Melanie made smart decisions. Besides, isn’t that what most horror films hinge upon – protagonists putting themselves into precarious situations?

A genuinely psychological horror film, Wyatt Garfield’s cinematography develops an ominous tone that feeds off of the luscious backdrop of the Irish landscape and architecture. The real world seems to exist on the precipice of something truly evil, with the evil world occasionally seething its way into the real one. Tully focuses on the notions of good and evil, while also questioning how we think of people who are complicit in evil acts. Don’t Leave Home suggests that when religion falls into manipulative hands with ulterior motives (namely power and wealth) it can become menacingly evil. Religion has been used countless times to initiate (and justify) wars, just as it has been used to restrict the rights of specific demographics (gender, sexuality, and ethnicity). Ireland, specifically, is certainly no stranger to religious-based wars or Catholic hospitals that punished unwed mothers by forcibly adopting their babies (the latter is most likely an influence on Don’t Leave Home).

– Don Simpson (@thatdonsimpson)