A Conversation with the Filmmakers of ANTHROPOCENE: THE HUMAN EPOCH

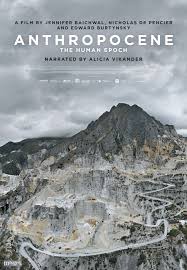

I met with directors Jennifer Baichwal, Edward Burtynsky and Nicholas de Pencier at the Sundance Film Festival on Friday, January 25, 2019, to discuss their new documentary Anthropocene: The Human Epoch (which I also reviewed). The movie – part of a trilogy that began with Manufactured Landscapes and Watermark – takes the viewer on a multicontinental journey through the myriad ways the human race has irrevocably altered the planet, and how the pace of that alteration is accelerating. There is a modern-day scientific push to have the name of our era officially designated the “Anthropocene” (a change from the current “Holocene”) to reflect the effect of homo sapiens on the environment. Narrated by actress Alicia Vikander in carefully measured tones, Anthropocene: The Human Epoch is also beautifully photographed, creating a visual fantasy that elides nightmare and daydream in a mystical, almost trance-like experience. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

I met with directors Jennifer Baichwal, Edward Burtynsky and Nicholas de Pencier at the Sundance Film Festival on Friday, January 25, 2019, to discuss their new documentary Anthropocene: The Human Epoch (which I also reviewed). The movie – part of a trilogy that began with Manufactured Landscapes and Watermark – takes the viewer on a multicontinental journey through the myriad ways the human race has irrevocably altered the planet, and how the pace of that alteration is accelerating. There is a modern-day scientific push to have the name of our era officially designated the “Anthropocene” (a change from the current “Holocene”) to reflect the effect of homo sapiens on the environment. Narrated by actress Alicia Vikander in carefully measured tones, Anthropocene: The Human Epoch is also beautifully photographed, creating a visual fantasy that elides nightmare and daydream in a mystical, almost trance-like experience. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: So, I have not seen the previous two films in this trilogy, but it’s interesting because you, Jennifer, are the one officially credited as the director for the first film, then you and Ed both for Watermark, and now it’s all three of you listed as directors here. So, with each new entry in the trilogy comes an additional director. Tell me, please, about the trilogy and how this film fits into it.

Jennifer Baichwal: Well, first of all, we didn’t set out 13 years ago to make a trilogy and say we’d be working together for 13 years. It all happened quite organically. Nick and I are married and have been making films together for 25 years. Manufactured Landscapes was the beginning of our collaboration with Ed. The film had such an impact around the world, and its approach…I mean environmental documentaries have quite a specific kind of tone usually, right? They’re urgent, they’re somewhat polemic, they’re kind of doom-and-gloom, there’s a little bit of hope at the end, but that’s the way they go…they’re exhortative, they’re meant as activist tools, in a way.

What we were trying to do, in the way that Ed’s photographs work, is to create this non-didactic kind of experiential understanding of these places we’re connected to but would never normally see. So it started there, and it resonated with people, so we just thought, “Oh, we’re not done with each other yet; we’ll keep going.” And then in Watermark, Ed wanted to learn more about directing, and so took on that role, and Nick’s a cinematographer and … he’s … I don’t care about the division of authority, you know, the division of names in that way. But we developed that more, it was about people’s interaction with water all around the world. And then this one feels like it’s kind of the culmination of everything that we’ve ever talked about for 13 years, thinking about human influence on the systems of the earth on a global scale and in geological time.

Chris Reed: So regardless of credited roles, these have really been three collaborative projects, and you, Nick, have been the Director of Photography on all of them? I know you are on this one…

Nicholas de Pencier: I shot this one and Watermark, and for Manufactured Landscapes, I was the producer.

HtN: And Ed, Jennifer mentions your photographs, so are you primarily a photographer who has then become a filmmaker?

Edward Burtynsky: Yeah, I’ve been a photographer since around 1980. I went to school and studied photography, and in ’82 began this investigation of large-scale, man-made adventures in the landscape, culminating to the point where I went to Bangladesh and did “The Shipbreakers of Bangladesh.” At that point I became intrigued with Asia as a subject matter, and then went to China and spent, I think it was…the trip that Jennifer and Peter Mettler, who’s the cinematographer on Manufactured Landscapes, went on. It was my fifth time to China, but each time we’d go for a month at a time over a period of three or four years, and kind of look at how the industrial revolution had gone from the West to China, but also re-emerged in China on a scale that’s almost mind-boggling.

So there’s an opening shot in Manufactured Landscapes, that Peter and Jennifer devised, that tried to expand one of the images that I took, kind of looking down aisles of manufactures. It was an eight-and-a-half-minute opening shot which is still discussed, I think, in film courses on documentaries. At first, when I first saw it, I thought, “I don’t know if this is going to work,” because I was starting to get impatient, myself. I was like, “When is this going to end?” But then, when that impatience stops, you go, “Holy s***. This just keeps going.” I’ve never seen anything quite like this.

JB: That was the whole point of that: how do you intelligently translate a still photograph into a time-based medium? And Peter and I grappled with it a lot. And that shot…we could have done it so many different ways, but literally, it’s a dolly shot through a factory that is 3/4 of a kilometer long at walking pace, so it’s a whole magazine of film, and I knew it was going to be the opening when we finished it, because it was the perfect expression of scale in time. You do get bored, and then you get mad, and then you come out of that into an understanding of scale.

Jennifer Baichwal, Edward Burtynsky and Nicholas de Pencier

HtN: Absolutely. This is often what happens with a long take, and particularly if it’s done well. Now I really want to see that film even more than before! So, this new movie comes with a multidisciplinary project. Can you describe that project?

NdP: We set out from the very beginning, the three of us, to design this conceptually by following the scientists who were researching the Anthropocene and mustering enough evidence to see if it could be officially ratified. So we were looking at the content, but then also looking at the best ways to express that content. We have made a museum-exhibition show with Edward Burtynsky of large-scale photographs, super large-scale murals which are now technically possible at high resolution, augmented-reality virtual sculptures that you can see through tablets and phones with an enabled app on some of these subjects, and video installations.

We also have an education component. There’s a big website, there are two books…and of course the documentary that’s here. We wanted this to be a virtual circle of different ways into this topic depending on what your interest would be, and that they would all reinforce each other and be different planes of a multi-prismatic approach.

HtN: So, this film is about the human impact on the planet and the increasing effect that it’s having on the environment. How did you choose your specific locations?

JB: Well…it’s been a five-year project, so we researched for about a year, then shot over two years, and then we edited for a year. We used the research categories of the Anthropocene Working Group. The film, and the whole project, really was inspired by their research, and they have been, for 10 years, gathering evidence of human impact on the earth’s systems, at levels that we probably don’t understand, like anthroturbation, or human tunneling under the earth. Long after we’re gone, these tunnels that we make for subways and sewers and mines and parking lots will still be there. Technofossils are human-created materials that persist in the biosphere. Aluminum, concrete, plastic, you know, they’ll be around forever.

They estimate that the technosphere is 30 trillion tons, the aggregate of all human-created materials. So, we used their research categories as our way into exploring this because their argument is that we’ve tipped the planet outside its natural limits through our influence. And so, that’s the way that we came at the project and then we looked for the best examples of each of these research categories that we could find in the world.

EB: It’s always been a problem in my work from back in 1982 when I began to think, “OK, I want to do copper mines. Which one?” So I looked for the ones that had been around for a long time because the imprint on that landscape will be larger and greater, so the scale would be present. So, looking for the largest in scale and longevity, the ones that have been mined for long periods of time, I think we’re also presenting this kind of…beyond-the-pale scale that we were looking for, that can then be translated through a still image or through film.

And as with an exhibition of photographs, you’re not told exactly what to think. So, it’s more revelatory than accusatory, so you can then see the film and you have to walk away and form your own opinion. We feel that’s another way to shape consciousness, rather than telling somebody, “Think about it this way,” which really narrows the view of how somebody can interpret that material. I think working with Jen and Nick was really interesting to try and take some of the things that would be the experience of an exhibition and try to build that into the experience of the film.

NdP: I would add, just about the specific locations, that we had kind of a war room in Ed’s house for months and months. Ed’s traveled around a lot, as have we. So, we needed to represent each of the categories, the places that we would eventually fix on. We also wanted a portfolio, a planetary portfolio, so we shouldn’t be too heavy in one place. In the movie, we are in every continent except Antarctica. We go to 22 countries, 44 locations, to try and make that planetary representation real. And there has to be visual interest, there have to be layers of meaning and complexity in a place, too, so that we really resonate these issues and make people think.

HtN: At what point did you bring on Alicia Vikander as your narrator, and why her?

JB: I was writing the narration. I kept writing it, revising it, running downstairs and recording it, then running up and putting it back into the edit room, and, you know, just…everybody hates the sound of their own voice but, God, this was just, like, “Get me out of here.”

NdP: It wasn’t that bad, Jennifer.

JB: No, but I…so we were thinking, the omniscient “voice of God” narrator is always a guy, which bugs me. I mean, it’s just…think of one film you know where, especially a documentary, that has been narrated by a woman.

HtN: The Ingrid Bergman documentary narrated by…wait for it…Alicia Vikander!

(everyone laughs)

A Still from ANTHROPOCENE: THE HUMAN EPOCH

JB: So, I was trying to think of, “OK, whom do I really respect as an actor? Who has a beautiful voice? Who has an environmental consciousness?” And she was the first person who came to mind … and she’s young and has this hopefulness. But we don’t make features, so we’ve never done casting or anything like that, and it just became this thing of, “OK, here’s her agent. We’re going to write to them.” And she said, “Yes.”

It was the easiest thing in the world, except … then she was traveling a lot so scheduling it was so difficult, and we ended up recording it three days before our first press screening for the Toronto International Film Festival. It was incredibly stressful, like getting it in, getting up at 4 in the morning to record it, and then Nick had to go to Spain to meet her and … then we’re cutting it. We finished it that night at like 1 or 2 in the morning and then got it over to the lab. It was heavy.

HtN: Wow! But at least you were picture-locked, by that point, so you knew exactly what you needed her to say and when. But still, that’s crazy.

JB: She was beautiful!

NdP: You would think if you take four-and-a-half years to make a film that it doesn’t need to be a mad screaming panic at the end, but it absolutely was. I did the flight, we recorded the next day in Europe, Jen and the sound team got up super early in Toronto to have the live-source connect, be able to give notes back, and they literally cut it and dropped it into the mix and finished it in one day.

HtN: Just crazy!

EB: Yeah. The nail-biter.

HtN: Wow. Always rushing at the end, no matter how well-prepared we are…So, the film really is beautifully photographed, and Nick, you’re the Director of Photography but you’re working with a team. Can you describe your approach to filming? It has this wonderfully unified feel throughout. Whether you were shooting things yourself or directing people to shoot, what was your particular sort of aesthetic in mind?

NdP: That’s great to hear and thank you. Absolutely, that responsibility is shared among a number of collaborators, and this was such a big, complicated project. In retrospect, I think we couldn’t have achieved what we achieved without…a lot of us have been working together for 13 years and we know, on a subterranean internal level…whether it’s Mike Reid, our fantastic drone operator, or whether it’s Ed…someone has to get to these huge places and you just say, “This is too…we’ve got to divide and conquer. Ed’s going to be directing some, Jen and I are going to peel off and talk to people.” But I think we all knew intuitively, and especially given the previous collaborations on the films, what the pace and what the style were going to be: that contemplative, reflective, really experiential style.

JB: It’s also a question of, if something doesn’t draw you in aesthetically, you’re not really going to pay attention to it. And I have to say, sometimes we get nailed by more hardcore activists who say, “You’re not ringing the bell loud enough. Like this is…we’re in a crisis here. We need to be way more strident about this message.” And we would argue: “No. Actually, it’s a much bigger tent when you can have a conversation with people who don’t agree with you.”

So, we’re trying to bring people in as it’s photographed, and to draw them in to a kind of dialogue through the compelling aesthetic window, and then hopefully a shift in consciousness occurs when you realize that you are connected to these places. You’re responsible for them in a large measure, some people way more than others, obviously. We in the global north are more responsible than people in the global south, but we’re all part of them, we’re connected to them. That’s also part of the approach in this kind of meditative but aesthetically seductive way of exploring the material.

HtN: There’s always a danger, when you’re making a film which has this doom-and-gloom message, to some degree, of losing people because it’s too much.

JB: Yeah.

HtN: You’re overwhelmed with a sense of how you can’t do anything, and so, I think it’s a smart approach to make it beautiful so that you’re drawing people in with the visuals, so maybe they’ll pay attention beyond that. And with that, I want to thank you very much for meeting with me. I enjoyed the film and hope you have a great festival.

JB: You, too.

NdP: Thank you.

EB: Thank you.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)

Like what you see here on Hammer to Nail? Why not pay just $1.00 per month via Patreon to help keep us going?