(The Seventh Fire, Jack Pettibone Riccobono’s powerful doc on Native-American disenfranchisement, boasts an all-star likeup of Executive Producers with Natalie Portman, Terrence Malick and Chris Eyre. The film is in limited release now)

We have long grown accustomed, in these no longer very “United States” of America, to see our role in the world as mostly, if not exclusively, positive. Certainly, in the first half of the 20th century, where we twice added our military might to the two major global conflicts of that era, very few would question the ultimate good of our actions. True, we dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, and the debate on the morality of that decision goes on, and rightfully so. Perhaps, however, the greater crime against humanity committed in our nation’s name began to take place a hundred years earlier, as our government enacted policies that would systemically destroy the culture and lives of the native peoples of this land, all in the name of something called “manifest destiny.” Oh, and then there’s that whole legacy of slavery and racism against African-Americans, not to mention discrimination against other non-European immigrants (and sometimes even against poorer European immigrants, as well). We’re nothing if not extremely human, prone to acts of courage and goodness, as well as extreme barbarism.

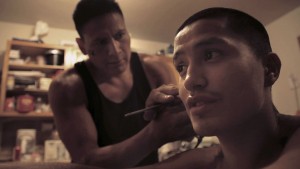

With The Seventh Fire, first-time documentary-feature director Jack Pettibone Riccobono tackles, indirectly, the troubling history of Native Americans. He follows two men, 37-year-old Robert Duane Brown, Jr. – whose Ojibwe name is Two Thunderbirds – and his 17-year-old nephew Kevin Fineday, Jr. (whose native name we never learn). A lifelong truant, Rob is preparing to serve a fifth jail sentence, for drug dealing, when we first meet him. His nephew appears set to follow in his footsteps, eager to step up and earn his place in the world, as a man (as he sees it). We’re in Pine Point, Minnesota, on the White Earth Indian Reservation, and there doesn’t seem to be a lot to do, other than sell and take drugs, for white and Native Americans, alike. It’s a bleak world, ready for the time of “the Seventh Fire,” a prophecy that foretells the moment when the Ojibwe (who call themselves the Anishinaabe) will choose to rebuild their nation and culture.

Despite his life of crime, Rob comes across as an extremely thoughtful man, plagued by the demon of addiction. When he’s in prison, the enforced sobriety leads him to work on an autobiographical novel in which he envisions a better future for himself and his people. Unfortunately, whenever he’s outside, in the real world, he cannot stay away from drugs and alcohol. What is remarkable in this movie is how present we are in both environments. Riccobono’s camera captures the contemplative Rob and the drunken and stoned Rob. We are there, as a true fly on the wall, as Rob is locked up, and there as a witness to the violence at the parties he attends on furlough. No one is immune from the twin scourges of drugs and lack of opportunity. A mother snorts meth while holding her child; a young man works the crowd at a powwow, slipping packets of white powder into the hands of youth and elders, alike, all the while avoiding the gaze of an addiction counselor trying to find him.

That young man is Kevin, who talks as if he is wants to embrace his culture – such as it is, at present – yet cannot break away from the temptations of the easy money of the gangster lifestyle. He has no role models, since those who came before him, like Rob, took the easier path, as well. Then again, the more we learn about Rob, the more we know that there has been nothing easy about his life, ever, so perhaps we should withhold judgement. Indeed, Riccobono asks us to observe and empathize, rather than judge. And in so doing, with fleeting references to the larger context of Native-American disenfranchisement, the director ends up telling an extremely powerful and sad story about a different kind of “manifest destiny,” one with very little hope for those on the losing side of history. It’s a film remarkable for its level of raw, unfettered access to its subjects, filled with images both beautiful (perhaps a tribute to executive producer Terrence Malick’s own work) and devastating. Whether a cleansing fire does, indeed, flare up, something needs to change. Perhaps a movie like this can provide the spark.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)