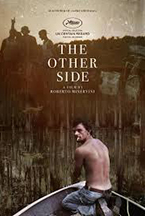

THE OTHER SIDE

(Director Roberto Minervini’s The Other Side has been impressing and disturbing audiences and critics for the better part of a year. The film will finally see limited release in theaters on Friday, May 20.)

Let me say, from the outset, that watching The Other Side made me deeply uncomfortable. Director Roberto Minervini – a Texas-based Italian filmmaker living, working and studying in the United States for some time now – embeds himself with a group of disenfranchised individuals in Louisiana in a way that feels both intimate and exploitative. He trains his lens on drug addicts, convicts, and members of a paramilitary group who all share a sense of anger at the way their lives have turned out, and at being left behind by the rest of society. In this Deep South, the multicultural world from which Minervini hails exists as a distant bogeyman, a convenient causal scapegoat for all that ails his protagonists. Whatever my discomfort, it is a testament to the director’s commitment to presenting the truth as his characters see it that he resists any overt editorializing, allowing them to speak for and about themselves. As such, it is a haunting, profoundly disturbing movie.

First, a word about about methodology. In the world of documentary filmmaking today, we frequently discuss hybridity and the use of fictional elements in an ostensibly nonfiction genre. A look at the selections at the recent 2016 Sundance Film Festival reveals a number of films in the documentary category – from Robert Greene’s Kate Plays Christine to Michal Marczak’s All These Sleepless Nights – where the director appears to guide actors/subjects in front of the camera as they perform in carefully crafted scenes. In Joshua Oppenheimer’s 2012 Oscar-nominated The Act of Killing, the director asks the perpetrators of the 1960s Indonesian genocide to reenact their crimes. To paraphrase French film theorist André Bazin’s seminal question: “Qu’est-ce que le documentaire?” When does directorial control push a documentary into fictional territory? If we believe – as I do – that the simple act of framing an image alters the nature of on-screen reality, then aren’t scripted elements just an extension of this? What about films like Touching the Void and American Splendor, which are half-reenactment and half-documentary; in which genre do they fit? If “cinema is truth twenty-four times a second,” (a quote from French New-Wave director Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 film The Little Soldier), and if the appeal (or is it?) of a documentary film is that it supposedly represents something truer than fiction, then perhaps it’s worth exploring how fiction affects this truth.

I have not seen Minervini’s previous three films – The Passage, Low Tide and Stop the Pounding Heart – what he calls his “Texas trilogy,” but here he seems to combine the traditions of fly-on-the-wall vérité filmmaking, where the camera is all but invisible, with a strongly motivated narrative purpose. For two thirds of the movie, we follow Mark – veteran, convict, drug abuser – as he walks through his life in a near-somnambulant haze, drugging, drinking and even having sex. Both he and his live-in girlfriend, Lisa, seem unaware of their observers, and yet the quarters are so close, how could this be? Minervini, in the movie’s press notes, discusses how filming comprises only 20% of his production time; the rest is spent developing rapport. Then, with a stripped-down camera and minimal crew, he shoots twenty-minute takes. Later, he and his co-writer, Denise Ping Lee, confer with the subjects about what was captured, and decide on what comes next. In this way, all parties have a say in the direction of the story, although the ultimate decisions reside with Minervini, as director. What emerges is a raw portrait of hopeless poverty that cannot help but feel – even with the obvious acquiescence of Mark and Lisa and everyone else – as if a savvy outsider is using the misery of others for story material.

Fortunately, for us and for Minervini, despite these questionable ethics, the film rises far above the level of mere poverty porn. Minervini gives these folks a voice, and though that voice may be unpleasant (and racist), it is genuine. When, in the final third of the film, we jump to a profile of a paramilitary group (seen briefly in the pre-credit sequence), we discover how these same feelings manifest themselves in the hands of the slightly less disconnected Louisiana locals. They are the ones who have come home from fighting abroad without Mark’s subsequent descent into drugs and crime, yet still feel left behind by the global economy, and have chosen to arm and train themselves in anticipation of their freedoms being taken away. Of course, they blame Obama, and one of the most distressing images in the film is towards the end, when a group of these armed whites blow up a car stuffed with an effigy of our President. Is that even legal? Could this film, showing that and explicit drug use, be used as evidence of crimes committed? And why are there a few black faces in the background (I would have liked to see a conversation with those good people)?

Whatever one’s ultimate feelings about Minervini’s methods and his relationship to his subjects, there is no question that The Other Side holds your attention, even if that attention is tinged with no small amount of revulsion. Forget what you think when you hear the words “documentary” and “fiction” and embrace the unvarnished nightmare of “Minervism,” where the truth emerges from the proximity to the lives of real people, scripted or not. The Other Side is a movie to experience, if not to savor.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)