(The purpose of Milestone Films’ ‘Project Shirley’ is to re-introduce the best available prints of Shirley Clarke’s work to audiences across the world. The Connection opens in NYC at the IFC Center on Friday, May 4, 2012. Visit the Milestone website to learn more. NOTE: This review was first published on Thursday, May 3, 2012 as a “Hammer to Nail Pick of the Week” at the Filmmaker Magazine blog.)

Usually when you watch a once-banned film decades after the fact, it leads to a deflated feeling that the film wasn’t ban-worthy at all, that it wasn’t ever close to being “dangerous.” But when one of those films is also widely deemed a classic by trusted sources? Well, that just about guarantees it’s going to land with a big, whopping letdown of a thud. So here comes a restoration of Shirley Clarke’s 1962 feature, The Connection, a film that 1) was banned upon its initial release, and 2) is considered to be a landmark achievement in American independent cinema. With a double-expectation like that, there’s no way it can deliver, right?

Wrong. Maybe it’s due to the pristine restoration that has removed any celluloid aging from the technical presentation itself (credit here goes to the UCLA Film & Television Archive with funding by the Film Foundation). Or maybe it’s the electrifying live jazz music that is played throughout. Or maybe, just maybe, it’s all that and more. In the tradition of John Cassavetes’ Shadows or Jim McBride’s David Holzman’s Diary, The Connection is one of those seminal works that wears its date proudly on its rolled-up sleeves even as it winds up to deliver a present tense punch.

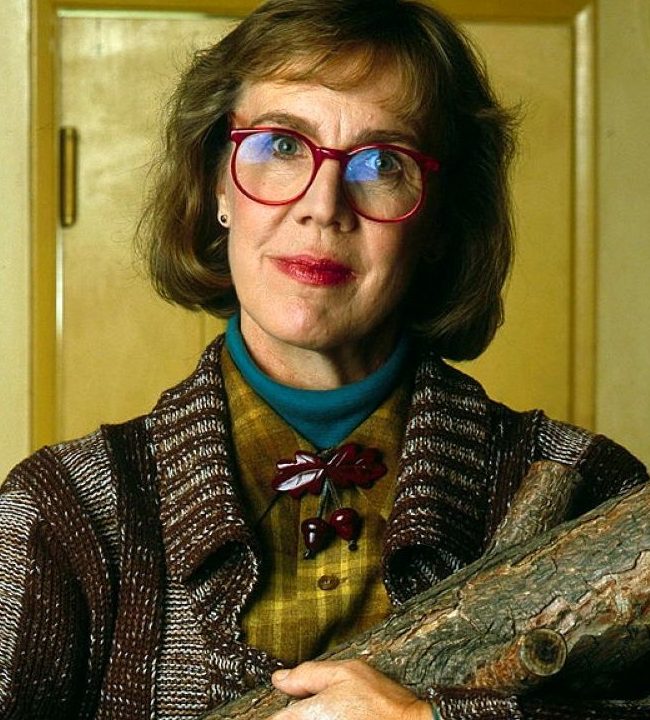

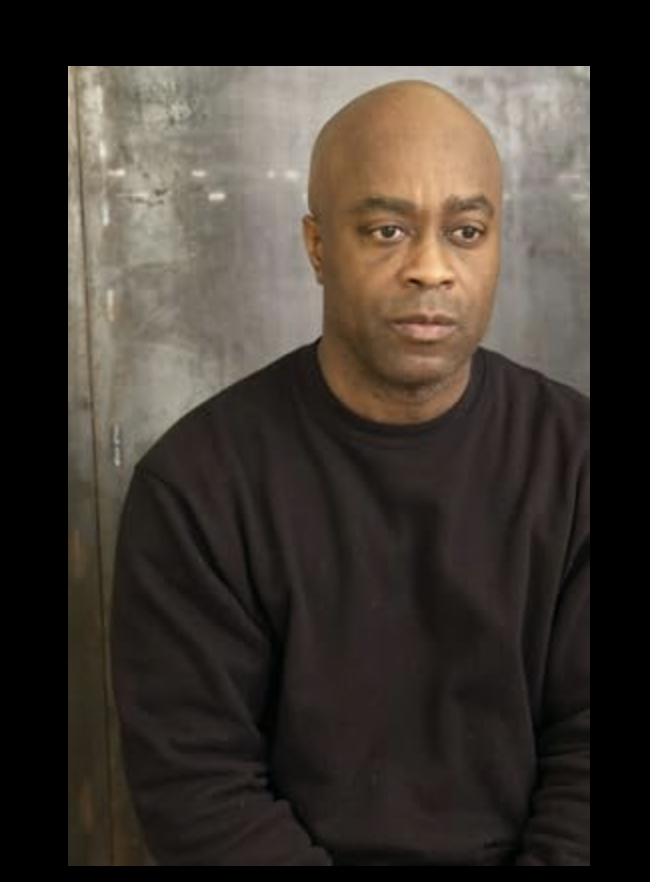

Yes, Clarke’s film is stagy, but not because it was made in the early 1960s. That’s because it was based on an Off-Broadway play by Jack Gelber. Set in a Greenwich Village loft over the course of one seemingly real-time afternoon, eight junkies wait for their connection, Cowboy, to arrive and replenish their veins. Gelber, who was brought in to adapt his story for the screen, took a bold stylistic leap by inserting the act of filmmaking into the film itself. The Connection opens with a title card that sets up the scenario: on this particular day, Jim Dunn, a clueless white documentarian, has used the connections of his black cameraman J. J. Burden to infiltrate this apartment and point his cameras at these men to capture junkiedom in its rawest, purest form. But when Cowboy shows up with an old religious white woman (in order to throw the police off his scent), Dunn’s curiosity gets the better of him. He wants to know why these guys are so tempted by this stuff.

Yes, Clarke’s film is stagy, but not because it was made in the early 1960s. That’s because it was based on an Off-Broadway play by Jack Gelber. Set in a Greenwich Village loft over the course of one seemingly real-time afternoon, eight junkies wait for their connection, Cowboy, to arrive and replenish their veins. Gelber, who was brought in to adapt his story for the screen, took a bold stylistic leap by inserting the act of filmmaking into the film itself. The Connection opens with a title card that sets up the scenario: on this particular day, Jim Dunn, a clueless white documentarian, has used the connections of his black cameraman J. J. Burden to infiltrate this apartment and point his cameras at these men to capture junkiedom in its rawest, purest form. But when Cowboy shows up with an old religious white woman (in order to throw the police off his scent), Dunn’s curiosity gets the better of him. He wants to know why these guys are so tempted by this stuff.

In that bleak final act, whether it’s because we ourselves have been trapped in one location for such a long time (even though Clarke and her cinematographer Arthur J. Omitz cover the set from many different perspectives and employ their own form of visual jazz) or because Cowboy’s “medicine” has begun to take effect, the humor and groovy vibe begins to drain out of the picture, leaving behind a dejected room of sad, defeated men. Though a graphic shot of a needle injection was likely the most direct reason for the film’s ban back in the day, the general depths to which this scene sinks certainly didn’t do it any favors with the powers that be. By the end of its roughly 100-minute run time, The Connection makes viewers feel just how desperate and useless heroin addiction is. (Its inextricable link to jazz music is another essay/film/study altogether.)

Back in 1962, Clarke’s conscious decision to use herky-jerky camera sweeps and film rollouts must have added an air of sloppy docu-illusion for already nervous viewers. But 50 years later, though these self-conscious techniques certainly won’t fool anyone into thinking they’re watching an actual documentary, Clarke’s formal rigor comes off as quite forward thinking. Like the most groundbreaking films, The Connection is a distinct snapshot from yesteryear whose impact doesn’t diminish over time. It hangs around, man.

— Michael Tully