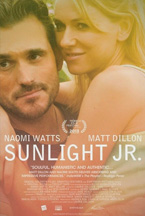

SUNLIGHT JR.

(Sunlight Jr. is now available on DVD, Amazon Instant, and at iTunes. It opened theatrically on Friday, November 15, 2013. It world premiered in the “World Narrative Competition” at the 2013 Tribeca Film Festival. NOTE: This review was first published on May 2, 2013.)

Laurie Collyer’s third film Sunlight Jr. is branded as a film about working class America. This is notable because fictional narrative films, even independent ones, rarely have an overt political consciousness. On a formal level it makes sense. Fictional films informed by political and social issues tend to telescope into character studies, and for good reason—it’s pretty difficult to express political consciousness through character without proselytizing. A character-driven narrative follows the demands of aesthetics first, and social justice only if it’s important to the filmmaker, or a defining feature of the story’s world (and filmmakers are not historically from marginalized groups, but I don’t really want to get too sidetracked here).

Collyer’s first film was the documentary Nuyorican Dream, a scrappy, blunt look at a Puerto Rican family’s struggle to make it in New York. She followed this with Sherrybaby, defined by Maggie Gyllenhaal’s award-winning role as a mother on parole trying to stay sober and reconnect with her daughter. Collyer says that Sunlight Jr. was inspired by Barbara Ehrenreich’s book Nickel and Dimed, an account of the journalist’s undercover, experiential investigation of minimum-wage labor. So Collyer’s willingness to build her films around class, and to feature characters dealing with issues that predominantly affect the poor, does support the notion that she’s a “political filmmaker.” But it’s interesting that the reviews and interviews I read left out what for me was the most distinguishing feature of Sunlight Jr., that it’s a film about abortion. To be fair, the film touches on many things: the economy of Southern Florida, living with a disability, the foster care system, not to mention relationships, family, and having faith in other people. To reduce the film’s meaning to any one of these flattens its complexity. But what resonated most with me, and what has been conspicuously absent from other readings of the film, is Collyer’s representation of pro-choice politics.

The film opens by introducing us to Melissa (Naomi Watts) taking a shower and getting ready for work. We get a sense of her life pretty quickly through the exhausted way she puts on her cashier’s uniform, the darkness of her crappy motel room, and the resigned way she wakes her boyfriend Richie (Matt Dillon) to ask him to drive her to work. On the way they run out of gas, and Melissa has to jog in the rain to the convenience store where she works (called Sunlight Jr). It’s only then that we learn that Richie is in a wheelchair, the result of an accident several years back. One of the strengths of the film is the way Collyer establishes this fact then refuses to define Richie’s character by his disability. Melissa is impatient at work, hanging on to the job not only for the minimum wage but also for the company’s college scholarship program that she hopes to qualify for. But her dreams of education don’t extend much beyond wishfully flipping through the brochure, and clashes with her uptight boss signal that her chances are unlikely.

While Melissa spends all day shelving energy drinks and snack cakes, Richie loafs around with his buddies at the motel and drinks enough to keep a steady buzz going, spreading his disability checks and cash from electronics repairs pretty thin. What sells the relationship is context, made literal in the form of Melissa’s scuzzy ex Justin (Norman Reedus), an aggro wannabe who rolls around in his pimped out car, stalking the aggravated Melissa and trying to push pills on her. By comparison, Richie and his good intentions certainly seem like a step up. Dillon plays Richie with a jowly, gruff sweetness, but there’s also chemistry and desire between him and Melissa, which we see pretty clearly in the film’s overt sex scene.

Collyer’s narrative technique is to build up Melissa’s world then slowly break it down. It’s a disarming approach that proves her understanding of class—Melissa is poor not only because of the things she doesn’t have, but because of the choices she doesn’t have. This takes the form of Melissa unintentionally getting pregnant, which she reveals to Richie by casually picking out some baby clothes at the thrift store. At first he’s elated, and so is she. But when a health scare sends her to the hospital, Richie’s response is to flip out over the medical bill. He keeps promising that he’ll take care of Melissa, but it’s clear that he has no understanding of the kind of sacrifices and preparations becoming parents would require of them. Collyer raises the stakes by having Melissa lose her job, and when they can no longer pay for the motel they are forced to stay with her mother Kathleen (Tess Harper), an alcoholic with a run-down house full of foster kids. Harper nails this role, telling us everything we need to know about Melissa’s upbringing (and fears for her unborn child) with an economy of words and actions. Case in point: even though they’re sleeping in their car, Kathleen tells Melissa, “Richie never hit you, so you did good there.”

There are bed bugs, and barely enough chicken nuggets to go around, and still Kathleen and Richie’s only concern is their next drink. Increasingly desperate, Melissa even reaches out to Justin (who’s her mother’s landlord and neighbor), but he casts her off. The doctor at the clinic gave her a blank notebook to keep for her baby during her pregnancy, and all she’s written in it is “fuck.” Fed up and exhausted, Melissa makes the difficult, jaw-clenching choice to go to the clinic and have an abortion. Then she eats a bag of powdered donuts and takes the bus home. It’s resolute, and dispensed with without excessive drama. And this is what gave me such respect for Collyer’s film.

For middle and upper-class movie characters, an unintended pregnancy is usually presented as a matter of will. It’s an emotional, psychological, or lifestyle choice; it’s about the suitability of the partner and the woman’s career aspirations, not money. And almost every time the woman decides to have the child. If that is unlikely or problematic given the story or her character, she’ll conveniently have a miscarriage, a way to dodge the question of what Judd Apatow called “shmashmortion.” Knocked Up was billed as progressive, but they couldn’t even articulate abortion, let alone consider it as a plot point. That was in 2007, when two of the biggest Hollywood hits of the year—Knocked Up and Juno—were about accidental pregnancies. In contrast, arguably the best independent film of that year was Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, set in Communist Romania under the Ceauşescu regime, about a young woman who goes to harrowing lengths to help her friend secure an illegal abortion.

Now here we are in 2013, and even HBO’s edgy critical darling Girls disappointingly opted once again for the deus ex machina miscarriage. In a country that declared abortion legal decades ago, with a supposedly liberal entertainment industry, why are realistic representations of abortion in film and television so few and far between? An abortion was a part of the plot in the 1987 movie Dirty Dancing, not to mention Fast Times at Ridgemont High, which came out in 1982. It’s hard to imagine similar films making that choice today.

I know I’m putting a lot of emphasis on this one aspect of Collyer’s film, and it’s worth saying that Sunlight Jr. also has craft to recommend it. Collyer’s cast give subtle, solid performances, particularly Tess Harper as Melissa’s mother. And production designer Jade Healy does a great job creating a plausible yet specific world for the camera (the devil of Southern Florida really is in the details). But while I appreciated those elements, ultimately they were far less important to me than Collyer’s willingness to frame a question of reproductive rights in such a realistic way. It’s a brave choice, and so is the one her lead character makes.

— Susanna Locascio