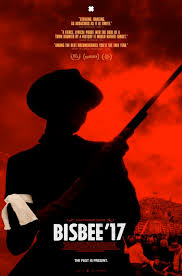

A Conversation with Robert Greene (BISBEE ’17)

Bisbee ’17 is a new documentary from director Robert Greene about the 1917 miner deportation in Bisbee, Arizona, that left hundreds to die in the desert. By organizing reenactments with the townspeople, Greene blends narrative form through a focus on the process of performance—a tool he’s previously employed to startling effect. The film opens September 5th at New York’s newly revamped Film Forum, with a nationwide release to follow.)

Bisbee ’17 is a new documentary from director Robert Greene about the 1917 miner deportation in Bisbee, Arizona, that left hundreds to die in the desert. By organizing reenactments with the townspeople, Greene blends narrative form through a focus on the process of performance—a tool he’s previously employed to startling effect. The film opens September 5th at New York’s newly revamped Film Forum, with a nationwide release to follow.)

Hammer to Nail: Where did you grow up?

Robert Greene: I was born in Charlotte, North Carolina. But I moved around a lot because my parents had trouble paying the bills. My grandmother was a Brooklyn jew, and so when I came up here I was like, “Oh, so this is who I am.” Wherever we were living, that was not who I am, but New York felt like who I am.

HtN: What drew your mother-in-law to Bisbee in 2003?

Robert Greene: She’s from Seattle. She’s a historian, and would take my wife on trips everywhere. She’s always looking or these types of places, and when she found Bisbee, she had an opportunity to get a house. It’s crazy cheap to buy a house there. At the time my wife and I had just started dating. We were sort of together, but not really, and she left the city to go work on the floors of her mom’s house in Bisbee and asked, ‘do you want to come help me?’ and I said ‘sure.’ So I came, and we started stripping the paint on this old mining cabin, and I just fell in love with the town. It probably has a lot to do with falling in love with my wife. There’s something about the desert, it’s just a different way of life that I felt I could relate to. It was the only place I liked to be outside New York. The survival instincts of New York are the same as the survival instincts of the desert. When the deportation happened, it was the Wild West still.

HtN: How did you go about organizing the reenactments?

RG: On our first trip we went with Bennett Elliott my producer and Jarred Alterman my D.P. with $1,000 and a camera and the goal was just to test some lenses and talk to people. Immediately we realized we are already shooting this movie. I didn’t even have the fully fleshed out idea in those first few trips. We had a historical consultant, Katherine Benton-Cohen, one of the leading experts on the deportation. I was writing scenes based on the research she had done, and we were casting based on people’s relationship with the story. It wasn’t just, ‘we needed characters,’ every actor needed a deeper resonance with the characters they would be playing.

HtN: Did you hold auditions?

RG: Auditions weren’t important. The audience had to know who the person was before they played the role. It was the relationship with the real people that was more important than acting chops. We needed a John C. Greenway, and Bennett told me she found this guy, an actor named James West, and he wants to interview. And I thought, ‘an actor? I dunno, I’m not sure.’ Then we met James and he was incredible, and he told us before acting he actually used to deport people for a living.

HtN: Did any of them say no?

RG: Some people thought we would trivialize it. Some people, like the artist Laurie McKenna, weren’t sure at first, but then once they figured out what we were doing they got onboard. A lot of people took convincing. It was tough to convince Doug Graeme, who is Dick Graeme’s son—they were on the side of the deporters. My dream scenario was if we could get Doug Graeme to drag Fernando (the central miner) down the street, then that would have meant he believes in what we were doing. He’s a tough guy who runs the mines now, and believes what he believes. The idea that we could create that image was exciting.

HtN: When did you know that Fernando would be the emotional core of the film?

RG: I asked Bennett to get me someone who we can dress up as a miner, just to test stuff. I saw a picture of Fernando and said, ‘eh too pretty’—I mean he’s gorgeous. We interviewed him by the pit. He was supposed to show up at 9am but he didn’t get there til 10:30, and I was getting frustrated wasting time, but then he walked up the hill and I was like ‘oh my god, it’s him.’ He had tears in his eyes because him and his boyfriend had just broken up. I was stunned by the way he naturally communicates that emotion on camera. It was very clear that he had something special. He loved Bennett, he connected with her much more than he connected with me. So trust your producers!

HtN: Your project reminded me a bit of the Stanford Prison Experiment. How do you think the process of making the film affected the psychology of those who participated in the reenactments?

RG: During Sundance (where the film premiered), and for a while, my answer to this question has been, “I don’t know.” But we had a screening a few weeks ago in Bisbee, and it was a really cathartic experience for everybody. I think I can speak for most of those involved that this was a very positive thing. There is this question of, “should you raise the ghosts of the past, or should you bury them?’ In terms of the Stanford Prison Experiment, the moment we said action on the day of the reenactment downtown, I did not direct them to go at each other the way they did. And they did. That was eye opening to me. We had conjured this…

HtN: You didn’t expect that intensity…

RG: Not at all. I didn’t script those lines. It was traumatic and cathartic at the same time. But ultimately people feel positive about it now.

HtN: The story of the two brothers was particularly impactful. I can understand, especially in today’s climate, the fear of the ‘other,’ but how could you deport your own kin?

RG: The xenophobic aspect is an important part of the story, but the deportation was also a political question. Because they were the IWW union, someone can label them and say ‘we don’t want socialists.’ When those radical ideas hit regular folks, you could end up deporting your own brother. The tragedy there was that the political division was grossly exaggerated. Most of the people who were rounded up that day were not socialists. They wanted better wages and better working conditions. They wanted Mexicans to be able to work above ground. They weren’t bomb-throwing radicals.

HtN: Across all your films you have a unique form and process. What do you look for when searching for you next project?

RG: Obsessiveness. I’ve been thinking about this story for 12 or 13 years. The IWW meeting the idea of the Wild West is about performative mythologies. That’s exciting to me. If you understand why we perform our myths, you understand America. With my last films, I stumbled on this technique of using performance in documentary that reveals those mythologies. There’s a tension between the performer and the process. The process stuff is meant to pull you much deeper into understanding. And in this film I want you to understand why America keeps doing this again and again.

*This interview was edited for length and clarity.

– Matthew Delman (@ItsTheRealDel)