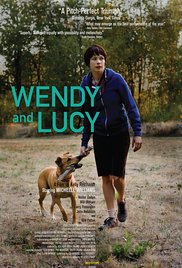

ON THE FRINGE, PART EIGHT: WENDY AND LUCY (2008)

There is an astonishing, heart-rending scene toward the middle of Kelly Reichardt’s pitch-perfect, Wendy and Lucy, an ascetic touching-without-being-cloying chronicle of a nomadic young girl (Michelle Williams), her dog Lucy and her broken-down car stuck outside of Portland, Oregon on her star-cross’d way to find work in Alaska.

There is an astonishing, heart-rending scene toward the middle of Kelly Reichardt’s pitch-perfect, Wendy and Lucy, an ascetic touching-without-being-cloying chronicle of a nomadic young girl (Michelle Williams), her dog Lucy and her broken-down car stuck outside of Portland, Oregon on her star-cross’d way to find work in Alaska.

After losing Lucy – perhaps the only real support she has at this nearly impossible point in her devastated life – as a consequence of being apprehended and briefly detained for shoplifting dog food, we find Wendy sitting in the bleak Walmart parking lot that has more or less become her temporary headquarters.

She converses with the old security guard who spends all day (literally, all…day: 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., six days a week) “standing here with my hands in my pocket” who, though nameless throughout the course of the movie, has become Wendy’s only “friend” while she tries to figure out what the hell to do next.

WENDY: Not a lot of jobs around here, huh?

SECURITY GUARD: [chuckles] I’ll say. I don’t know what the people do all day. Used to be a mill, but it’s been closed a long time now. Don’t know what they do…

WENDY: You can’t get a job without an address, anyway. Or a phone…

SECURITY GUARD: You can’t get an address without an address. You can’t get a job without a job. It’s all fixed.

WENDY: That’s why I’m going to Alaska. Hear they need people.

Hear they need PEOPLE. Incredible.

The fact that Wendy and Lucy came out to stentorian critical acclaim (winning multiple awards, including AFI’s Movie of the Year and Cannes’ Palm Dog, an actual award given to “Best Canine Performance,” while Reichardt herself was nominated for the slightly more prestigious Un Certain Regard Award) in 2008, the most economically dire year in recent American history, is significant.

This fact makes Wendy and Lucy more than a brilliantly conceived, concise character study of a young, hard-luck woman on the road with her dog. It is also an unfortunate time-capsule of the desperate existence of far too many disenfranchised persons – young and old alike (as embodied so well by the old security guard in this scene and the rest of the brief moments in which he appears) – across the nation, lost, bewildered, frustrated and, worst of all, feeling completely impotent in changing their seemingly “fixed” circumstances.

The universality of Wendy and Lucy can be seen via its wide recognition as something of an inspired, contemporary update of Vitorrio De Sica’s Umberto D. (1952), a compatriot film about a person (in this case, the old, ostensibly obsolete man himself) wandering the streets with little purpose and only his trusty, loyal, spritely dog to keep up his spirits and, indeed in this heartbreaking work of Italian neorealism, to be a reason to live at all.

Wendy and Lucy is at its root a story of the homme moyen sensuel that works so wordlessly in relaying its point, that it could have come out today, in 2008, in 1930, 1979 or 1952. In America, Europe or just about anywhere else in the world.

The trick here being Wendy and Lucy’s absolute cinematic quality, its total ability to show–not-tell, as per the ultimate foundation of premium moviemaking, its total ability to enrapture the audience watching, whether in a theater with others or at home alone, via the film’s spartan minimalism that relies on almost no other factor than its series of interconnected images exhibited onscreen.

Wendy and Lucy has almost no soundtrack whatsoever.

There is the opening lilting hum, courtesy Williams’ disembodied voice, that is one-part Mia Farrow’s haunting dirge in Krzysztof Komeda’s eerie introductory score for Rosemary’s Baby, and one-part Donovan’s similar introduction to his late-sixties rock-pop song “Hurdy Gurdy Man.”

And there is a brief interlude of muzak playing in the grocery store where Williams’ Wendy makes the mistake of attempting dog food larceny before being caught and sent into a tailspin that would kick-off most of the conflict of the rest of the picture. (Incidentally, these two mini-scores are the same; we realize in said grocery store scene that Williams/Wendy was humming the irritatingly memorable grocery store muzak.) There is an appropriately flat and droning ambient score that ends the film during its final credits, as well.

Otherwise, there is not a moment of music in Wendy and Lucy. It is a cold, gray and desolate film, just as its story and character development demands.

The few actors in the film – including a perfectly restrained Will Patton as the mechanic who seems subtly empathetic of Wendy’s car problem but also pragmatically indifferent to yet another customer who might not be able to pay her bill – seem to telegraph in their emotionality and facial expressions virtually nothing.

Truly, each of the performances in the film are extraordinarily disciplined, lacquered with spartan restraint. Our cast members are left expressing themselves with an indescribable purity that cannot be relayed via movements of eyebrows, lips or other traditional physiognomic Poker tells (or what actors call “externalities”) that normally help the audience connect with and comprehend what the characters onscreen are going through.

Actors and director work throughout Wendy and Lucy in an uncanny tandem system – and, yes, this includes Lucy the dog, who could not have had any difficult competition for her well-deserved award from Cannes.

The scene excerpted between Wendy and the security guard is in fact most likely the longest dialogue sequence of the picture. (If you were to look up “Wendy and Lucy scene” on YouTube, you would immediately be directed to a clip of this short, three-minute exchange in a film that is otherwise feature-length.)

Transcending a typical art film a la the mesmeric canon of Stan Brakhage, Reichardt (who teaches at the university level about and works within the community of art filmmakers) has produced a project that is wholly accessible to a general audience (stellar performances by recognizable actors such as Williams and Patton sure do help) while being a quintessential representation of what some have referred to as “pure cinema.”

“Pure cinema” being an artistic movement in recent film so esoteric that it has elicited almost no press as a “scene,” despite plenty of outstanding analyses filed about its member films and its being, essentially, a contemporary revisitation of cinéma pur, an almost century-old artistic methodology whose star proponents included dada/surrealist artists Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp and René Clair.

In focusing almost exclusively on the movement and visual rhythms of cinematography and editing, these examples of “pure cinema” are also the spiritual progeny of the works of Hungarian master Béla Tarr, who created a cache of spellbinding, hypnotic films throughout the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Tarr is the modern filmmakers’ filmmaker. His is an almost inhuman employment of lengthy, uncut sequences and supremely prolonged tracking shots that conjure a nearly surreal orchestration of actors, scenery, background action, props and locations into a kind of ineffable “real time” ballet that can be as captivating during movement and stasis alike.

Whether presenting – uniquely uncut – a chaotic, domestic argument taking place in 1979’s Family Nest; or a mysterious shadowy figure going up and down a tall building’s elevator in 2007’s The Man from London; or the drudgery of an old man and his daughter boiling and eating their potatoes without exchanging a word in their dilapidated, electricity-free shack in 2011’s The Turin Horse (alleged to be the still-living maestro’s final film), Tarr has done more than establish a breathtaking body of cinematic art whose products often require theater managers to place a telltale “No refunds will be given” sign on their box office windows when screening such sui generis pictures that are not for the timid moviegoer seeking out the next big Marvel movie spectacular or creative machination of the indie darling du jour.

Tarr has created a series of tools to be similarly employed by future filmmakers who would watch his movies and understand how to so purely manipulate and control cinematic space-time in a way that hadn’t previously been thought possible.

There had been inklings of such notions in the playful cinematic meanderings of Andy Warhol’s Factory crowd: a nearly half-hour short in which a man gets a haircut, a five-hour-plus “feature” in which a man sleeps…or the infamous Empire, an eight-hour-plus static shot of the Empire State Building; most filmgoers attending special screenings of Warhol’s opus will often bring pillows and sleeping bags.

There had, of course, been French wunderkind Chantal Akerman’s 1975 masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, a three-hour-plus meditation in which – as with successor Wendy and Lucy – there is almost no dialogue, a nearly non-existent cast and almost all “action” is confined to the compact spaces of “protagonist” (sort-of) Dielman’s bedroom and kitchen where she stands before the camera Julia Child-style and meticulously, soundlessly goes through the entire routine (more than a few times throughout the film) of making hamburgers, from cracking the eggs over the meat, to mashing the patties, etc., etc., etc. in a disquieting state of Kadavergehorsam.

Sounds painfully dull? To the point of wanting to tear out your eyes, or flee the theater, or throw your smart TV out the window? Fair enough. Akerman’s and Tarr’s films are not for everyone, as noted.

But those filmmakers for whom the likes of Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman and Tarr’s dreamlike Werckmeister Harmonies are effulgent inspirations include: Sofia Coppola (Somewhere), Gus Van Sant (his ambrosial “Death Trilogy,” perhaps the finest examples of this Tarr/Akerman-influenced “pure cinema” to date: Elephant, Gerry and Last Days), Steven Knight (Tom Hardy-starrer Locke), JC Chandor (the virtually wordless All Is Lost, in which Robert Redford, as solo actor, is credited in the end as playing only “Our Man”) and Israel’s Samuel Maoz (Lebanon; Maoz’s latest, Foxtrot, is in theaters now).

There has also as of late been an overlap of “pure cinema” into the mainstream fold: Danny Boyle’s 127 Hours, the opening half-hour of Pixar’s WALL-E and nautical thrillers Open Water, 47 Meters Down and The Shallows.

To be clear, these are not always films based solely in one location or showcasing a small number of actors, with little to no music or no effects along the lines of Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat or Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel. Nor are these live-theater-to-screen films (e.g., 12 Angry Men, Hitch’s Rope or Richard Linklater’s Tape).

These aforementioned films of “pure cinema” are, as with their exemplar Wendy and Lucy itself, those that could very well be told almost exclusively through a series of photos (think of Chris Marker’s 1962 French short film “La Jetée,” which inspired Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys).

There’s no other way to say it: Wendy and Lucy is pure in its cinematographic construction by writer/director Kelly Reichardt.

And this almost masochistic, draconian quality is essential for the film to truthfully present an unvarnished articulation of Wendy’s desperate helplessness. She has nothing aside from her car (which breaks down), her dog (which she loses) and a security guard (whose name she doesn’t know).

The filmgoing experience must grant the audience watching nothing but the objective imagery of what takes place, lacking any pretense, context, or (as exceptionally rare today), judgment. Wendy and Lucy must be a filmic representation of Stanley Kubrick’s famous statement that “[t]he most terrifying fact about the universe is not that it is hostile but that it is indifferent. However vast the darkness, we must supply our own light.” (Italics my own.)

Indulging in an absurd urge to supply my own light, I once followed up on a singular opportunity I had to meet Reichardt in person in an intimate, informal setting.

I happened to be in Rhinebeck at the time, right around when Wendy and Lucy first came out. Reichardt was teaching at the quaint hamlet’s renown liberal arts college, Bard, and I had seen her film twice at the theater already.

Wendy and Lucy was by far my favorite movie of the year (I in fact listed it as my entry for movies that were snubbed by the Oscars while writing for a new pop culture publication in Portland, Oregon, not too far from where the movie takes place), and I was as intensely affected by it – particularly (no spoiler here) by a single line barely murmured by Wendy in the last few minutes of the film – as I would later be by Reichardt’s previous and subsequent films, such as 2006’s Old Joy (another contender for my “On The Fringe” series).

As such, I was, well, not happy but fanboy-ishly determined to spending the flat rate of $20 to taxi from one side of the decidedly sybaritic town to the other to find Reichardt at her sylvan college campus. (It was raining, hard; I had no choice here, unfortunately, and had taken the train up from NYC, hence no rental car.)

She wasn’t in her office.

I paid $20 to taxi back to my seafaring-themed, cheap motel on the outskirts of the village. The next day, on my way to grabbing my train back down to NYC, I told myself I had to meet her. I had already blown $40 the day before. What would another $40 matter? I didn’t need to eat that week. So, I did it, made my $20 trip back to her office…and this time, she was there.

“Kelly?” I asked when I knocked on her open door.

“Yes?”

I entered and explained I was a young filmmaker and writer who had been pummeled by the power of her picture.

She politely asked if I’d like to sit down, and we spoke about Wendy and Lucy, her executive producer Todd Haynes (another hero of mine) and so-called “art films.” She remains quite the proponent of the fringe field, opting to have the space allocated for “extras” on the DVD of Wendy and Lucy to be used for short art films by her colleagues and friends.

While we were talking, I found myself subconsciously petting a muscular, friendly, golden-haired dog, before stopping abruptly. I dumbfoundedly peered up to Reichardt separated from me only by her cluttered desk. She nodded her head: “Yup, that’s Lucy.”

Now, not everyone will have the chance to pet Lucy the dog. Not everyone will have the opportunity to sit in Kelly Reichardt’s office and talk with her about movies, art films and Todd Haynes. But that comfortable, soothing, human and genuine experience I was lucky enough to have on that blistery, wet and gray day in mid-state New York is one that exists too in Wendy and Lucy.

It is the experience of not only “pure cinema,” but pure connection. From the viewer to the character(s) – yes, even an obliviously happy-go-lucky dog – onscreen.

I am so grateful I was able to meet Reichardt and her Cannes Award-winning dog Lucy that day. It is the same special, magical feeling that emerges when you watch her or fellow “pure cinema” filmmakers’ works.

It is so universal, that it must have been the same feeling of magic experienced by the earliest filmgoers attending the first screenings of the works by the Lumière Bros., Georges Méliès, Charlie Chaplin, Fritz Lang, Carl Theodor Dreyer, Robert Wiene and FW Murnau.

What happens when direct magic and such genuine truth of the homme moyen sensuel is brought together onscreen? We’ll see next week in 2012’s Louisianan picaresque children’s adventure story, Beasts of the Southern Wild.

MATHEW KLICKSTEIN is (for the time being) a Boulder-based writer/filmmaker who recently completed and has been touring his documentary on 80s/90s TV icon Marc Summers, On Your Marc, to be widely-released soon. His next book, Springfield Confidential: Jokes, Secrets, and Outright Lies from a Lifetime Writing for The Simpsons(co-written with lifetime series writer/producer Mike Reiss, foreword by Judd Apatow), will be released through Harper Collins this June. You can keep up with his regular shenanigans at www.MathewKlickstein.com.