THE CURBSIDE CRITERION: MULHOLLAND DRIVE

(Here at Hammer to Nail, we’re are all about true independent cinema. But we also have to tip our hat to the great films of yesteryear that continue to inspire filmmakers and cinephiles alike. This week, Ray Lobo takes a drive down David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. Like what you see here on Hammer to Nail? Why not give just $1.00 per month via Patreon to help keep us going?)

“Don’t play it for real until it gets real,” says Wayne Grace’s character as he directs Naomi Watts and Chad Everett at an audition. David Lynch’s masterpiece Mulholland Drive is a cinematic fever dream in which characters appear to be fleshly vehicles for what are perhaps ghosts from bygone eras, or perhaps dream images, or Hollywood archetypes, or even Pirandellian characters in search of an author. Lynch’s characters may be any of these or none of the above. If we cannot pinpoint Lynch’s intent, all the better. It is precisely these Lynchian mysteries that makes rewatching Mulholland Drive—this marks my fifth time—an activity that never grows old. With each rewatch, I latch onto something new, a new insight is gained, a new visual detail or line of dialogue gets stuck in my head. This time around it was Wayne Grace’s very deliberate instruction of “don’t play it for real until it gets real.” It is hard to say who or what is real–in the mundane sense of the word–in Mulholland Drive. In the last third of the film, however, things do seem to get real.

This much is clear to me: Mulholland Drive is haunted through and through. It is the ultimate ghost story. Folksy ghosts from Hollywood’s Golden Era and jitterbugging teeny-boppers cross paths with cutthroat mobsters and film noir characters who cross paths with cynical late 90s and early aughts sleazebags. And if all that were not enough, Lynch sprinkles in a cowboy straight out of an old Hollywood Western. All this makes Mulholland Drive, in similar fashion to Blue Velvet, a mashup of eras by way of Lynch’s play with genres. Mulholland Drive implodes time. Lynch’s brilliance lies in resurrecting characters/archetypes from bygone eras–characters whose existences were fractured, who were not allowed to fulfill themselves. Lynch’s universe is made up of shapeshifting ghosts who recur, haunt, and inhabit bodies. How appropriate that Mulholland Drive takes place in Hollywood and involves individuals—actors–whose very vocation requires them to serve as mediums for spirits—characters.

In a Lynchian universe it is very difficult to separate dream from reality. For most of Mulholland Drive’s runtime, that is exactly the case. But what appears real to us in a dream, as horrific as it may be, is alleviated by our waking. Lynch does not let us off that easy. There are instances in the film wherein the Real that Wayne Grace’s character mentions makes an appearance. That Real, that place of utter terror wherein language collapses and we are left speechless, does not seem dreamlike; in fact, that Real exists in the back lot of Winkie’s Diner. The last third of Mulholland Drive involves a takeover by this Real, this raw emotion, this trauma. Betty’s (Watts) love/obsession for Rita (Laura Harring) has an intensity that erupts in intense sex and when they sit together at club Silencio. The jealousy that burns through Betty/Diane is too irrational, too beyond words, too Real. Diane’s depression and pain seem too tangible to be a dream.

Apart from the metaphysical musings that Mulholland Drive inspires in the viewer, there are some truly humorous scenes. Scenes involving mobsters who are finnicky about their espresso, bumbling hired killers, and film directors who are pressured to compromise on their artistic principles give the film grounding and move it beyond the dreamworld. Our everyday experience is marked by these intrusions of humor and absurdity in serious moments. In that sense, Mulholland Drive captures our reality. And, on the topic of film directors having to compromise on their vision, there seems to be a lot of Lynch’s own personal experiences with ABC contained in Mulholland Drive. Stories abound about Lynch’s battles with ABC revolving around Twin Peaks and his original attempt to make Mulholland Drive a television series. Again, Justin Theroux’s character seems to be a vehicle through which Lynch can express his real-life experiences with television and film execs.

While Justin Theroux’s character is involved in scenes that seem very close to experiences had by Lynch, I try not to read too many of the scenes in Mulholland Drive as biographical or allegorical of experiences had by Lynch. It seems like a pastime for some commentators and fans to read Lynch’s movies as maps that plot out his psyche and past traumas. Perhaps a better approach, and it is definitely the one I recommend, is to place Lynch alongside the characters in Mulholland Drive. Just like those characters, we should see Lynch as a medium who communicates with and is inhabited by ghosts from bygone eras. Those ghosts speak through him and his films.

But the Real–selwyn’s pain, Theroux’s frustration about losing control over his movie, Diane’s love for Rita, her jealousy, and the deep emotion they feel when listening to llorando. There’s also the real horror of the real—the monstrous individual in the back of Winkie’s, Selwyn’s suicide, and the very real humor.

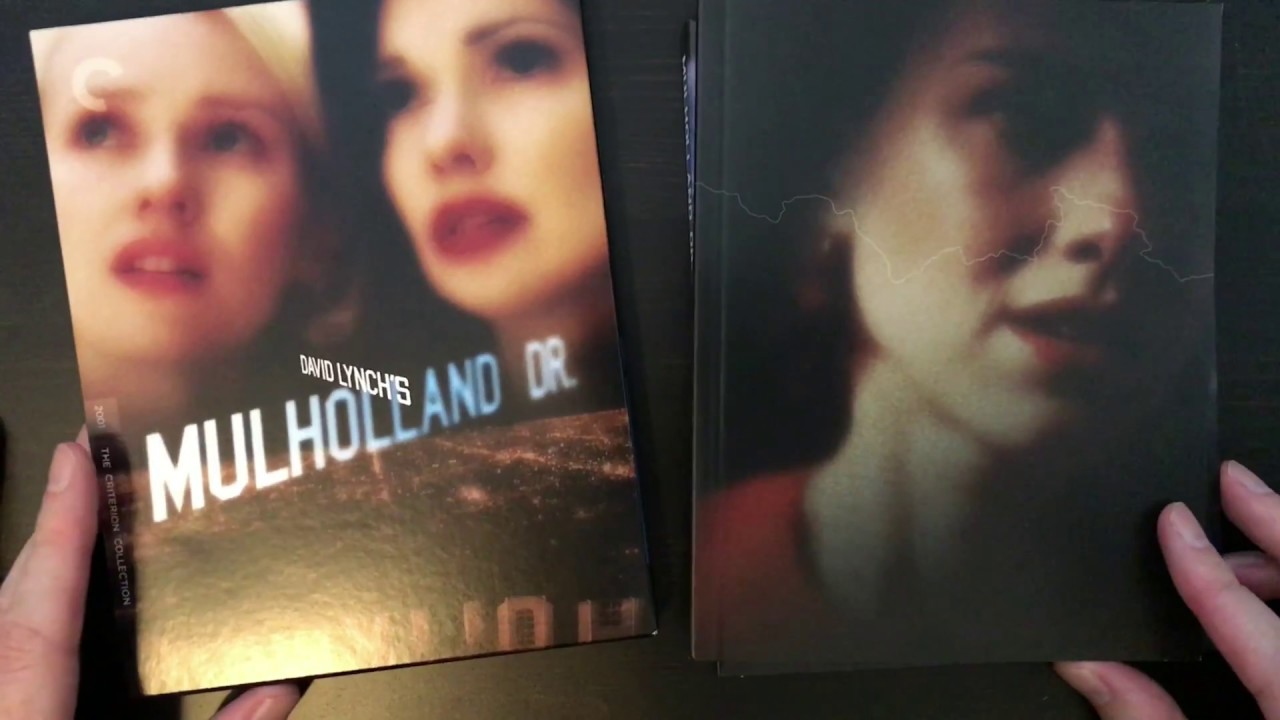

The Criterion 4k Blu Ray of Mulholland Drive features include…

- New 4K digital restoration, supervised by director David Lynch

- Interviews with cast and crew including Lynch, Naomi Watts, Justin Theroux, and Angelo Badalamenti

- On-set footage

– Ray Lobo (@RayLobo13)

Criterion Blu Ray; David Lynch; Mulholland Drive Blu ray review