(The 2021 Toronto International Film Festival runs Sep 9-Sep 18 in Toronto, Canada. HtN has a ton of coverage from the fest so stay tuned! Like what you see here on Hammer to Nail? Why not give just $1.00 per month via Patreon to help keep us going?)

The central drama of Mothering Sunday, Eva Husson’s dreamy adaptation of Graham Swift’s eponymous 2016 novel, does not take shape right away, and as befits the director’s elliptical style there are many detours along the road to the satisfying finale. Initially set in Southeast England’s Berkshire County in the years following World War I, in and among various properties of the landed gentry, the movie weaves backwards and forwards through different eras as it goes, reminding us that memory is the great time machine of the human mind. Agony and joy intertwine on life’s journey, and we can either take strength from their duet or lose ourselves in the abyss of one extreme or the other.

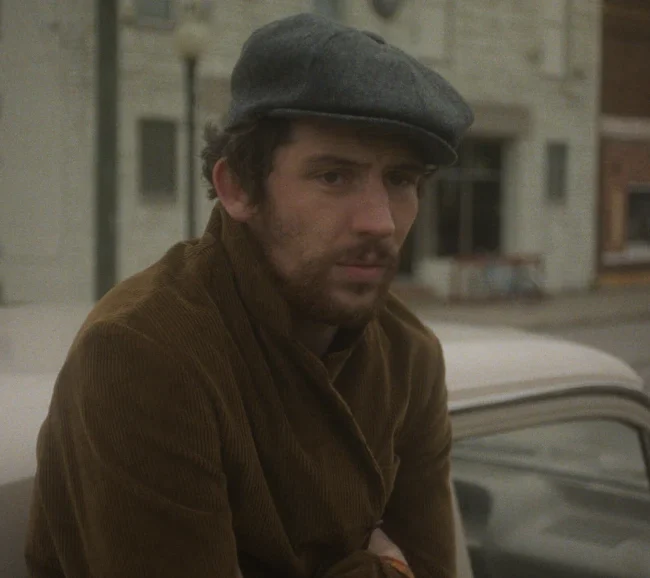

The protagonist, at least, is clear: one Jane Fairchild (Odessa Young, Assassination Nation), orphaned at birth and raised to be a domestic servant. Vivacious and smart, she reads voraciously, though that is not the source of her primary attraction to a local gentleman, Paul Sheringham (Josh O’Connor, Hope Gap), son of neighbors and good friends of her employer, Mr. Niven (Colin Firth, Supernova). Paul may find her mind appealing, but he has other things on the brain when he calls the Nivens up on Mother’s Day in 1924, hoping to reach Jane. As we soon discover, they have long been lovers, even though Paul is engaged to another young woman, Emma (Emma D’Arcy, Amazon’s Truth Seekers series), also of the aristocracy, who herself used to be engaged to the Nivens’ deceased son, killed in action. It’s all quite complicated, and also sad.

For there is a great grief that has enveloped these people, who otherwise have everything in life, which is the loss of their boys during the recent Great War. Mrs. Niven (Olivia Colman, Them That Follow) is almost catatonic, abiding sorrow her most defining characteristic. Paul is the sole male survivor of his generation, and so bears the burden of everyone’s expectations. As he tells Jane when she objects to the coin he gives her, “I’m spending for three.” So, why not give it away? Certainly, death and loss in World War I were hardly reserved for the wealthy, yet these folks know not what to do with themselves now.

In opposition to this upper-class despondency there is Jane’s constant energy and yearning. She wants to do, rather than just be, and in flash-forwards we get a sense of what she has made of herself, which is a writer of no small success. We also see her with a new man, Donald (Sope Dirisu, His House), a philosopher, and so guess that something has happened to end this early, melancholy idyll filled with sex and conversation. She loves Paul, and she clearly loves Donald, too, yet we also see her as an old woman with neither in the frame. What has she been through to make her dreams come true yet leave her in solitude? Still, if a life be well-lived, then perhaps tragedy is but an obstacle along the way, never to be forgotten but possibly to be overcome.

Young is a powerful and fearless performer, baring soul and body to portray a vibrant character with aspirations above her initial station. In contrast to the gentry of 1924, she knows what she wants, if not, at first, how to get it. The talented ensemble provides able support, bringing both humor and anguish in equal measure. Husson (Girls of the Sun) photographs the different sections in contrasting tones, all of it filled with evocative images. What, then, is the central drama? As much a narrative of personal growth as of upward mobility, Mothering Sunday is a tribute to perseverance and resilience. As Jane says, at the end, declares, “It was inevitable. The task was impossible. But it was wonderful.” Yes, indeed.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)