MONICA

(Check out Jessica Baxter’s movie review of Monica, it’s in theaters Friday via IFC Films. Seen it? Join the conversation with HtN on our Letterboxd Page.)

Despite recent progress (and plenty of setbacks), representational Trans cinema remains a barren landscape. Fortunately, we have an oasis in the form of Italian director Andrea Pallaoro’s new film, Monica, starring Trace Lysette. Pallaoro and his writing partner, Orlando Tirado, are no strangers to crafting intimate cinematic portraits of women in crisis. Charlotte Rampling won an acting award at The Venice Film Festival for helming their 2017 film, Hannah. Lysette received Venice Film Festival accolades of her own in 2022, when she became the first out Trans woman to star in a selected film.

Monica follows the titular character, a Trans woman working as a massage therapist in L.A. and in the death throes of a relationship with an unseen jerk called Jimmy. In between leaving voicemails for Jimmy, Monica is shocked to receive a call from Laura, the sister-in-law that she has never met. Laura lives in an unnamed Midwest town, raising 3 kids with Monica’s brother, Paul. It’s the same town Monica fled years before, when her mother kicked her out for being Trans. The mother who drove her away is now dying, but refusing hospital care, and the family needs Monica to lighten the load. We can guess pretty early on that the kind-hearted Laura is also hoping to facilitate a deathbed reconciliation for the family. Monica surprises herself by agreeing to come. She packs up her hot-but-janky convertible and makes the long drive to her trepidatious homecoming.

Monica is a stranger in a familiar town, meeting her sister-in-law and siblings for the first time. She hasn’t seen her little brother since Eugenia (the flawless Patricia Clarkson) told her she couldn’t be her mother anymore. No one in her biological family has ever met her as Monica. Every interaction she has outside the relative safety of Los Angeles is fraught with the prospect of conflict or even violence. So naturally, she proceeds with caution, ready to flee at the first sign of danger. She has learned this survival skill through experience. We don’t need to know specifics and the narrative doesn’t elaborate.

Monica enters her childhood home, where Laura “introduces” her to her own mother. That is partly because Eugenia has a brain tumor with a side of dementia, but it’s also because she deprived herself of the chance to see her daughter blossom. The question of how much Eugenia knows permeates every scene they share, until the question is finally answered definitively (but wordlessly). This is a uniquely Trans experience and the film does a wonderful job “translating” it for the uninitiated viewer.

Another Trans experience Monica illustrates well is the burden of emotional labor that Trans people carry at all times, in order to simply exist in the world. Monica spends so much time forgiving and conceding. She apologizes to people who should be apologizing to her, just so she can move on with her day. How exhausting to live in a constant state of grace like a Catholic saint because the world has decided it’s not ready for you to be yourself. Add to that the burden of expectation to forgive the transgressions of your parents on their deathbed. The truth is, you’re under no obligation to do so. If you do, it is such a loving gift, but it can also leave you with open wounds and no way to ever close them.

Despite the POV of Monica, (or perhaps because of it), the narrative also paints an empathetic portrayal of Eugenia. Patricia Clarkson is cast perfectly to convey a woman who has so much love to give, but dispenses it on a conditional basis. Even in her ailing state, she lashes out with a barbed tongue, but is so loving with her grandchildren. It paints a vivid picture of what it was like growing up under her supervision. She pushed away her child when they needed her most, but she also didn’t have anyone to help her understand what Monica was going through.

In a particularly poignant scene, Paul shows Monica a video he took of Eugenia speaking about a childhood incident when Monica advocated fiercely for her little brother. The camera stays on Monica’s face as Eugenia says, “I could never say no to [her].” Of course, that’s not true. She could and did say no to Monica at a crucial point in her life. But Monica softens at these words anyway. After all that hurt, Monica still wants her mother’s love and acceptance more than anything. This second-hand story conveys so much dimension in their relationship.

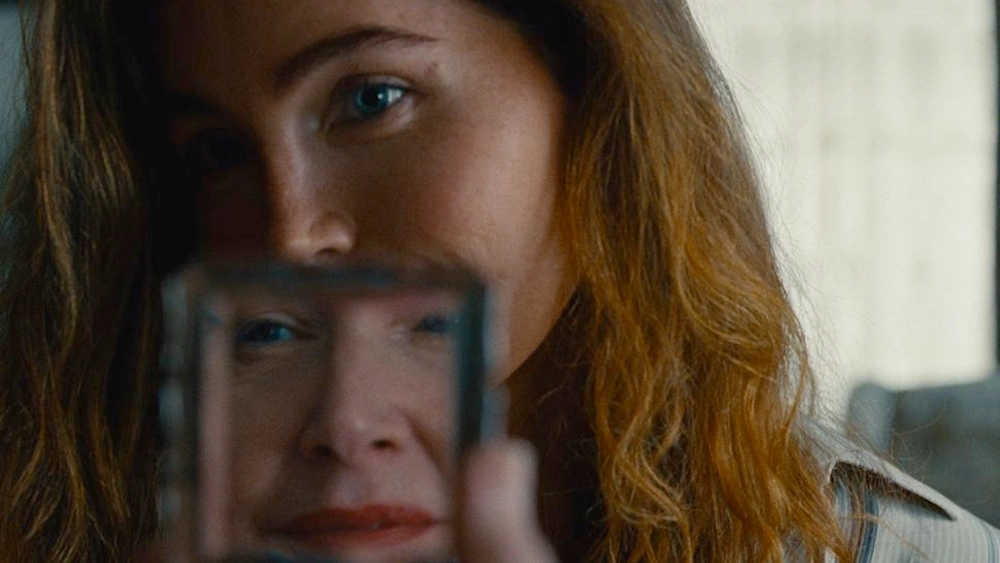

The key vibe in Monica is subtext. Katelin Arizmendi’s cinematography does a lot of work. Reflections abound to evoke themes of separation and contrast. The camera often lingers on Lysette’s face as people she hasn’t seen in years take her in. There is an indelible shot of Monica reposed in profile as she smokes a cigarette. In the background, out of focus, is an empty pool filled with vegetation. It’s a post-apocalyptic image that is not out-of-place in this present-day story. So many frames could be a prolific chronicle in their own right.

It takes a very delicate screenplay to convey a story like this without dipping into egregious exposition and melodrama, and it takes nuanced performers to pull it off. Phone calls (and excellent phone acting by Lysette) subtly serve crumbs of exposition. A strong supporting cast rounds out this heart-wrenching portrait. Emily Browning plays her well-meaning sister-in-law. Adriana Barraza is fantastic as the hired nurse that Eugenia prefers as her caretaker. Joshua Close as her brother, Paul, does an excellent job balancing past shared experience with present-day estrangement. Most of Monica and Paul’s conversations are about their childhood because they haven’t known each other as adults.

But the film’s not-so-secret weapon is Lysette and her expressive face, often shown in profile, but always speaking volumes. You might recognize Lysette from Transparent, where she played an important supporting role for a cis man who received heaps of praise for co-opting her experience. Lysette commands the screen, even when her character is falling apart. She always dusts herself off, and carries on in quiet dignity. She tells her brother she is happy “most days”. We don’t get to see much of that happiness, but there is an exquisite glimpse when she prepares for a date. Her mother is asleep. There is no one else around. She frolics in a common area of the house to a novelty club tune, forgetting her troubles for a brief moment. It’s a powerful scene, not just because of her unmitigated joy, but because she gets to express in it in a place that historically saw her oppression. As Lysette recently said in an interview “In the Trans experience, I can’t stress enough that joy is the antidote to the struggle, the ignorance and the pain. It’s what keep us going.”

One of the more refreshing aspects of Monica is the restraint it shows in depicting Trans trauma. A few key lines guide us to a very vivid understanding of how she came to be estranged from her blood relatives – how those easily filled-in blanks effect a Trans person long-term. The film is not about that initial trauma. We never see it, we only hear snippets, but there’s so much we can infer from the way Monica carries herself and relates to her family. These people are strangers to her because they all made a choice years ago, and no one ever moved to mend it.

The film also presents a number of universal family dynamics, particularly the cruel and confusing role reversal that occurs when a dying parent needs mothering from their child. But this story belongs to Monica and Monica alone. She is in every scene. And that makes it a Trans story. So now we’ve proven we can make Trans movies with Trans leads. And that cis director and writers can use their platform to champion Trans stories. How about we get trans writers and directors next time, too?

– Jessica Baxter (@tehBaxter)

IFC Films; Andrea Pallaoro; Monica movie review