(Hooray, Criterion! The Last Days of Disco is now available on Blu-ray and DVD.)

This winter, a friend called to invite me to an impromptu party on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Although a Native New Yorker, I have rarely ventured above 14th street, a fact of which I am proud and ashamed in equal measures. When I reached my destination, I waited on a marble bench in the mirrored lobby of an apartment building, the kind of pre-war brick number that has its name in cursive on the awning. A few laughing collegiates with loosened ties finally arrived and ushered me upstairs, where a group played trivial pursuit, their vodka tonics resting on the rug beside them. I felt déjà vu so powerful I was sure I had been here before, until I realized: I had just recently watched Metropolitan. My sense memory was simply the result of full immersion into Whit Stillman’s 1990 film, which lays bare a WASPy debutante season that has more self-imposed rules than Survivor. My first viewing of Metropolitan left me convinced there was a New York I’d never known, would never know, up and across town, where a party was a series of cleverness contests and no one walked the dog in sweats. The event I had stumbled upon wasn’t quite right (for starters, there were Jews present) but it was a reminder of the evocative power of cinema.

Metropolitan (Stillman’s first feature) introduced viewers to the intellectually charged and oddly puritan decadence of the UHBs—Urban Haute Bourgeoisie—a particular sub-genre of moneyed city mouse. The quippy confection of a screenplay, for which Stillman received an Oscar nomination, made it clear that the director was the UHB’s historian, archivist and court poet. Stillman’s cinematic voice is deeply specific, and deeply felt in the work it has inspired, from small films like Tadpole to unstoppable pop culture forces like Gossip Girl.

Stillman followed up Metropolitan, a polite teen romp where adults were hardly seen (a la Muppet Babies), with Barcelona, which tells the tale of Ted and Fred, a pair of UHBs let loose in one of the world’s sexiest cities, unable to use their knowledge of obscure political theory and silk neckties to advance their case with exotic women. Stillman’s first two films work best when thought of as sociological studies performed by a skilled, and thoroughly embedded, anthropologist: Metropolitan introduced us to UHBs in their natural habitat, while Barcelona showed us what happens when you release these creatures into a foreign climate.

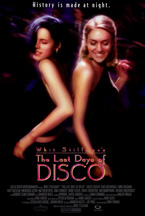

Metropolitan and Barcelona have remained available on DVD, with Metropolitan receiving the distinguished Criterion treatment. But for some reason, Stillman’s third—and arguably best—film, The Last Days of Disco, is now out of print and frustratingly hard to find. Much to my delight, however, Disco recently popped up streaming free on hulu.com. What an ironic way to view a film in which the characters struggle to make copies on clunky new Xerox machines.

The Last Days of Disco is the third installment in Stillman’s “Doomed Bourgeois In Love” trilogy. Unlike Metropolitan and Barcelona, which take place “not so long ago,” Disco belongs to a definite time, “the very early ‘80s.” This specificity strips Disco of the fairytale quality of its predecessors, but lends it a pair of sharp teeth. The film centers on Charlotte and Alice (Kate Beckinsale and Chloe Sevigny, both at their all-time best), recent graduates of New England institutions of higher learning. Assistant editors at a publishing house, they climb the career ladder by day and the social ladder by night as they maneuver their way into the city’s most elite disco nightspot. Tensions rise when the women, sharing an apartment much smaller than what they’re used to, zero in on the same potential suitor. Meanwhile, a financial scam threatens to shutter the club and put the last nail in the coffin of disco.

The Last Days of Disco is the third installment in Stillman’s “Doomed Bourgeois In Love” trilogy. Unlike Metropolitan and Barcelona, which take place “not so long ago,” Disco belongs to a definite time, “the very early ‘80s.” This specificity strips Disco of the fairytale quality of its predecessors, but lends it a pair of sharp teeth. The film centers on Charlotte and Alice (Kate Beckinsale and Chloe Sevigny, both at their all-time best), recent graduates of New England institutions of higher learning. Assistant editors at a publishing house, they climb the career ladder by day and the social ladder by night as they maneuver their way into the city’s most elite disco nightspot. Tensions rise when the women, sharing an apartment much smaller than what they’re used to, zero in on the same potential suitor. Meanwhile, a financial scam threatens to shutter the club and put the last nail in the coffin of disco.

If Metropolitan remains chaste, fully-clothed, and Barcelona strips down to its swimming trunks, then Disco, the most bawdy member of the troika, straight-up takes off its pants. Characters discuss cocaine and STDs with a frankness they once applied only to conversations about Jane Austen. Stillman has moved the party downtown and the decadence no longer takes the form of afternoon tea and copious cabs. Instead, we see sequins, exposed navels and Jaid Barrymore as a cougar in an alarming catsuit. (There is also a cameo from Igby Goes Down director Burr Steers, thus confirming my theory that a tweedy elk’s lodge exists somewhere above 75th street where the men who preserve “uptown” life on celluloid can be found palling around.) Characters from Metropolitan reappear, older now, and generations mingle as a fresh-faced Sevigny dances seductively with a (comparatively) graying Stillman-standard Chris Eigeman. The times, they are a-changing as the UHBs adjust to the fast money and loose morals of ‘80s New York, factors that will level the playing field and render their species almost obsolete.

Stillman sticks with a reliable stable of actors to portray his upwardly (and downwardly) mobile schemers, cartographers of the social landscape that would make Oscar Wilde proud. Stillman’s propensity for writing verbose characters that deal in pithy quotes has occasionally made him a victim of the Dawson’s Creek critique—aka, “Who actually talks like this?” (One girlfriend chatting casually to another: “The guys you like tend to be on the more ethereal side.”) Stillman’s scripts are written in what amounts to his own iambic pentameter. And, as with Shakespeare, it demands an actor learn a new cadence. The result: stilted, stripped-down performances that straddle the line between school play and British comedy in the best possible way. The impossible garrulousness of it all makes the moments of pure emotion, when characters are at a loss for words, that much more powerful.

Stillman’s trilogy is the cinematic equivalent of the Sinatra tune “It Was A Very Good Year,” an ode to luxuries lost and wisdom gained. In Kicking and Screaming, Noah Baumbach’s Stillman-esque movie about sedentary post-grads, Chris Eigeman’s Max proclaims, “I’m nostalgic for conversations I had yesterday. I’ve begun reminiscing events before they even occur. I’m reminiscing this right now.” Stillman characters, too self-aware for their own good, are deeply nostalgic for a time that has not yet ended. In Disco’s last scene, a worked-up UHB declares, “Disco will never be over. It will always live in our minds and hearts. Something like this, that was this big, and this important, and this great, will never die.” The fellow then boards a subway for the surreal credits sequence, a group dance-a-thon to the disco classic “Love Train.” Indeed, it is not yet dead.

— Lena Dunham