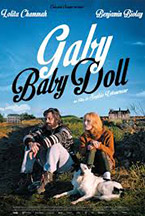

GABY BABY DOLL

(Gaby Baby Doll will hit American soil next week as part of the Film Society at Lincoln Center’s Rendez-Vous French Cinema series)

There’s a dryly funny moment in Sophie Letourneur’s 2009 breakthrough feature La Vie au Ranch where Lola (Eulalie Juster) meets up with her stodgy, nerdish boyfriend at a restaurant only to find him deep in an impenetrable conversation with a friend about the South Korean filmmaker Hong Sang-soo. Lola looks on helplessly as the two boys cycle through titles and snap judgments from the ridiculously prolific filmmaker’s body of work.

“Have you seen…?”

“Yes, but I found it lazy compared to his others.”

The pathological wit of the joke comes from the fact that a particular brand of arthouse moviegoer will know that Hong produces work at such a rate that the rapid-fire conversation could’ve lasted for so long that it becomes absurd, like the “did you read it?” episode of Portlandia; knowledge that immediately places you on the side of who’s being mocked. The viewer is made complicit in the joke.

There’s a similar moment in Lena Dunham’s Tiny Furniture (to which La Vie au Ranch is oft-compared, though it was made a year earlier), where Dunham’s Aura professes an allergy to subtitled films. If you’re watching Tiny Furniture in 2015, you’re probably seeing it through the inordinately fancy and ever-so-sophisticated Criterion label, complete with a bounty of commentary that proves that Dunham is no slouch when it comes to filmic knowledge. Both Letourneur and Dunham have a cunning ear for the way young men and women talk to each other, and have surely been on the receiving end of condescending diatribes from film student boys who wear their completism like over-compensational armor. Naturally, neither filmmaker ever gets enough credit for their own cinephilic proficiency.

Six years later, Letourneur delivers an explicit punchline to that Ranch joke in the form of Gaby Baby Doll; a film so clearly indebted to Hong Sang-soo both in theme and in craft that she even goes so far as to use his longtime composer, Yong-jin Joeng, for the minimal, playful piano score. She – and perhaps even her surrogate character from the earlier film – was into Hong all along.

Despite it’s Asian influences, locked off shots (the entire film is static save for one fantastically well timed push in), and lack of the improvisational screwball energy that defined Ranch as well as 2012’s self-reflexive film festival sex romp Les Coquillettes, Gaby is still heavily indebted to Joe Swanberg and American mumblecore. From its title, which sounds as though it could’ve been spat from an online Sundance film name generator, to the fact that lead actress Lolita Chammah bears a striking resemblance to Greta Gerwig – she has the same overtly expressive facial features, moves with the same gawkily graceful gait, and clearly shares a closet of sweaters and skirts with Frances Halladay, the titular character in 2012’s Frances Ha. Letourneur even takes indie film’s recent, inexplicable obsession with showing girls in tights peeing on camera to new heights by expanding it into a running gag that must take up something like forty percent of the film’s runtime. All of these unlikely influences, both Eastern and Western, are combined and distilled into an adult variation of a Gallic bedtime fairy tale.

Gaby is the same sort of neurotic, mildly self-obsessed twentysomething that Letourneur has become known for writing, except instead of being fixated on sex she only wants to sleep. She’s torturously afraid of sleeping alone, is stranded at a picturesque country house at the bequest of her therapist, and has just been dumped by her boyfriend, who has caught on to Gaby’s charade: she doesn’t actually love him, he’s just a means to a night’s rest. Frantically, finding herself with a condition eerily close to the one espoused by Canadian rapper Drake in his “Hate Sleeping Alone,” Gaby ventures to the nearby village in pursuit of a man to fill the empty space on her mattress. The local pub dwellers are ecstatically obliging, until they slowly discover that she has no interest in sleeping with them in the carnal sense. As Gaby grows to become known around town as a decidedly less lethal variant of Scarlett Johansson’s predator in Under the Skin, she quickly finds herself banned from the premises. Letourneur compresses and then expands time in a subtly magical/realist way as Gaby’s country exile progresses, and cinematographer Jeanne Lapoirie photographs the changing seasons to resemble gorgeous, ornate storybook paintings.

In spite of Chammah’s physically valiant comedic performance and the technical artistry on display, Letourneur’s inventively goofy take on The Princess and the Pea may have trouble finding an audience overseas. The humor is dependent on wordplay, and the homophones, alliteration, and subversions of turns of phrase don’t come across even slightly in the subtitles. Letourneur also occasionally seems less concerned with the plot than with exploring the obsessions of, and connections between, her disparate filmmaking idols. Still, Gaby Baby Doll will hopefully silence her vocal detractors from continually writing her off as a one-note comic exhibitionist. She’s a seriously talented auteur who deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as her influences.

— Mark Lukenbill