The Honeymoon Killers (1969) is more Cain than even James Cain himself. Martha Beck and Ray Fernandez, the film’s central lovers/killers, could easily take the place of any of Cain’s partners-in-crime. They’re just as cold-blooded and ruthless as duplicitous wife Phyllis Nirdlinger and insurance agent Walter Huff in Double Indemnity, and just as hot-blooded and passionate as vagabond Frank Chambers and restless waitress Cora Papadakis in The Postman Always Rings Twice. Yet unlike them, Martha and Raymond didn’t come from any author’s imagination—they came straight from the newspaper headlines of 1949.

The Honeymoon Killers (1969) is more Cain than even James Cain himself. Martha Beck and Ray Fernandez, the film’s central lovers/killers, could easily take the place of any of Cain’s partners-in-crime. They’re just as cold-blooded and ruthless as duplicitous wife Phyllis Nirdlinger and insurance agent Walter Huff in Double Indemnity, and just as hot-blooded and passionate as vagabond Frank Chambers and restless waitress Cora Papadakis in The Postman Always Rings Twice. Yet unlike them, Martha and Raymond didn’t come from any author’s imagination—they came straight from the newspaper headlines of 1949.

Though writer/director Leonard Kastle took some necessary liberties with the facts (everyone involved with the story was dead by the time the film was made), he stays true to their actual personages, the brutality of their crimes, and particularly to the almost mythic heights of their love for one another. Embittered, unloved, and obese, Martha (Shirley Stoler, in her first movie), a bossy nurse from Mobile, Alabama, is outraged to discover her sister signed her up for a lonely-hearts mail service—until she receives a letter from Raymond (Tony Lo Bianco). A con artist Casanova from New York, he sweeps her off her feet with romantic declarations. Yet when she visits him in the big city, he confesses to his scheme: he seduces lonely women through the mail, marries them, and then runs off with their money. Instead of being repulsed, Martha is fascinated. Partnering up, the two crisscross across the country, leaving weeping—and sometimes dead—brides in their wake.

Noir is a characteristically stylized genre. It has its own iconic dialogue, intonation, photography, location, and costume, to name but a few facets that immediately denote the genre. But, these are all superficial facets of the style, and Kastle does away with all of these, instead digging straight to the heart of the matter. He brings a refreshingly naturalistic interpretation to the poetry of desperation—sort of a fusion of Jim Thompson and Frederick Wiseman, if such an unholy (and awesome!) union were possible. Stoler brings something uncomfortably familiar to Martha’s pathetic sensibility. Her self-loathing is immediately recognizable. But unlike the noir-cliché of the woman dependant on her man, Raymond actually awakens an unknown power in Martha, and therein lies the contradiction that makes her so fascinating. She may be repulsed by her own self-image, but she radiates this magnetic power and sexuality that has Raymond hooked from their first meeting. He may think that he’s taking her along for the ride, but she quickly becomes the dynamic force that fuels their path of destruction.

Kastle made The Honeymoon Killers during a pivotal moment in American cinema. Old Hollywood and its Will Hays-monitored morality had collapsed. Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Easy Rider (1969), Midnight Cowboy (1969), and The Wild Bunch (1969) were not only challenging acceptable notions of on-screen violence and sexuality, but also redefining the way our country is portrayed cinematically. And with John Cassavetes’ Faces (1968) garnering both three Academy Award nominations (until then, reserved almost exclusively for Hollywood-made productions) and winning Best Actor for John Marley at the Venice Film Festival, American Independent Cinema was a capital letter movement like never before. These milestones provide not only context for The Honeymoon Killers, but also what Kastle was reacting to and, particularly in the case of Bonnie and Clyde, against.

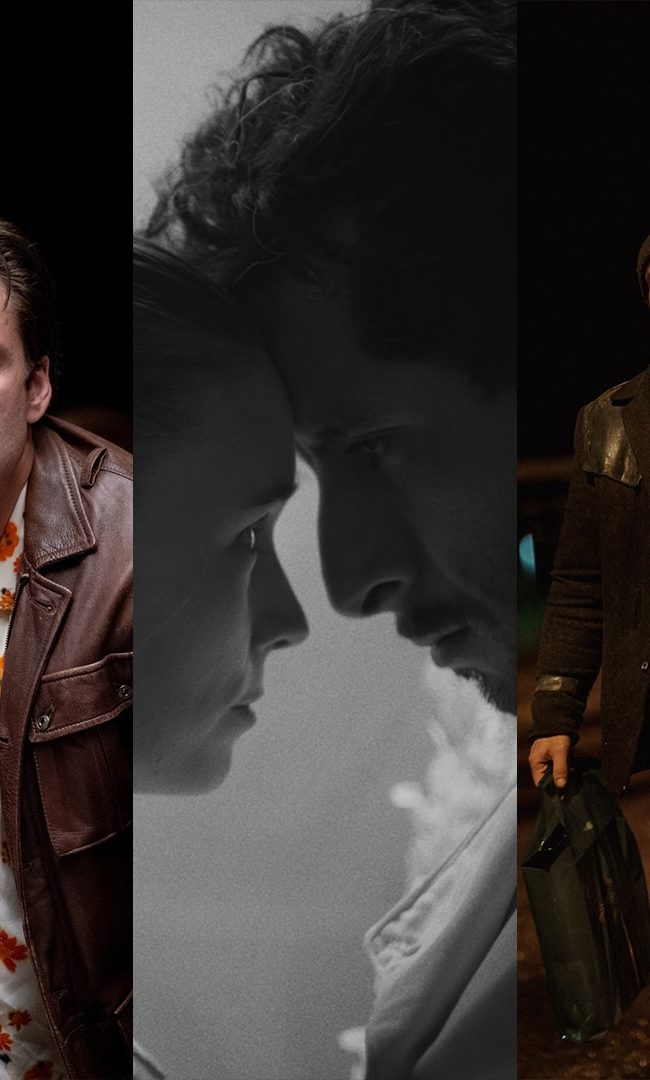

“I didn’t want to show beautiful shots of beautiful people in color,” Kastle has explained. Shooting in black-and-white, he and cinematographer Oliver Wood used a documentary style, which only emphasized the intimacy of the performances, as though they were truly stolen moments taken from reality. The stark look of the film, often making creative and economical use of domestic light fixtures, perfectly matches the raw emotions and deglamorized violence of Martha and Raymond. At points, the naked bulbs of bedside lamps seem to burn out the image—creating a blinding brilliance that almost hurts to look at. And it’s true: the nakedness of The Honeymoon Killers, far more primal and stripped down than the archetypical stylizations necessary to outwit the former Production Code, is not supposed to be pleasant to watch. It’s supposed to touch something deep down inside of viewers, to show us the desperation of these lovers, and the intensity of their fidelity, which is so strong that even murder seems paltry compared to their love.

The Honeymoon Killers exemplifies one of the credos of independent filmmaking, which is that cinema is no longer in the hands of the privileged few. In fact, most student films have a larger crew than the one Kastle used! It’s remarkable, downright extraordinary, that such a groundbreaking, sophisticated film should come from a first-time screenwriter and director who had zero experience or aspirations as a filmmaker. A composer by trade, it was coincidence and opportunity that brought Kastle to the screen for this, his only film. A friend of his was a television producer aspiring to make a feature film. This friend happened to have a connection that netted him the even-then low sum of $150,000, and he brought Kastle on board as a screenwriter. Up until then, the closest Kastle came to writing a script was writing an opera libretto. A young Martin Scorsese was engaged as a director but was quickly fired for spending excessive attention on a beer can in the bushes (according to Kastle, at least). After an assistant was also fired, Kastle was left in charge of the direction.

To labor over Kastle’s economy would be to discredit film’s rapturous illusion of reality, or its severe, unadorned nightmare of violence. It spares us nothing of the horror, yet exudes restraint and denies us the comfort of seeing the totality of the deaths. Shock fades quickly, but The Honeymoon Killers goes for something far more discomfiting. The authenticity of the film rings such that every time it plays, Martha and Raymond live and breathe, and love and kill, again.

— Cullen Gallagher

(The Honeymoon Killers screens this weekend at the Walter Reade as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s series “Mavericks and Outsiders: Positif Celebrates American Culture.” Or if you are unable to catch it on the big screen, buy the Criterion Collection DVD at Amazon.)