(The Headless Woman is now available on DVD through Strand Releasing. It opened theatrically in New York City at the Film Forum on Wednesday, August 19th, 2009. Visit the film’s page at Strand’s website to learn more.)

Lucrecia Martel’s The Headless Woman is a big, thick head scratcher of a foreign film. Is it a thriller? A comedy? A satire? A drama? A biting social commentary? Is it all of those things at once? Yes? No? Maybe? Maybe not? Martel is so evasive in her presentation that it becomes difficult to know if we’re putting in an unnecessary amount of mental work or if she has, in fact, provided us with all of the pieces necessary to complete this gorgeously cinematic—and utterly confounding—puzzle.

It is perhaps a credit to Martel that I find myself having such difficulty writing about The Headless Woman with even some semblance of coherence, as it’s so open to interpretation. But in this particular case, I can’t shake the feeling that this openness is somehow too open, that Martel’s detachment is too detached. I can’t deny that my brain was engaged in a novel way throughout the film, and I certainly can’t deny the allure of Martel’s distinct meshing of image and sound, but I also can’t deny that I never fully connected with The Headless Woman at any point, that it always felt like it was occurring out there somewhere.

Which brings up an even more confusing dilemma: if one considers the film’s subject matter and Martel’s goal of making us feel her character’s sense of foggy detachment, then she has certainly succeeded. So why have I seen the film twice, taken many worthwhile notes, and yet still find it hard to give in to The Headless Woman? Why do I admire Martel’s film and appreciate it but still feel underwhelmed by it?

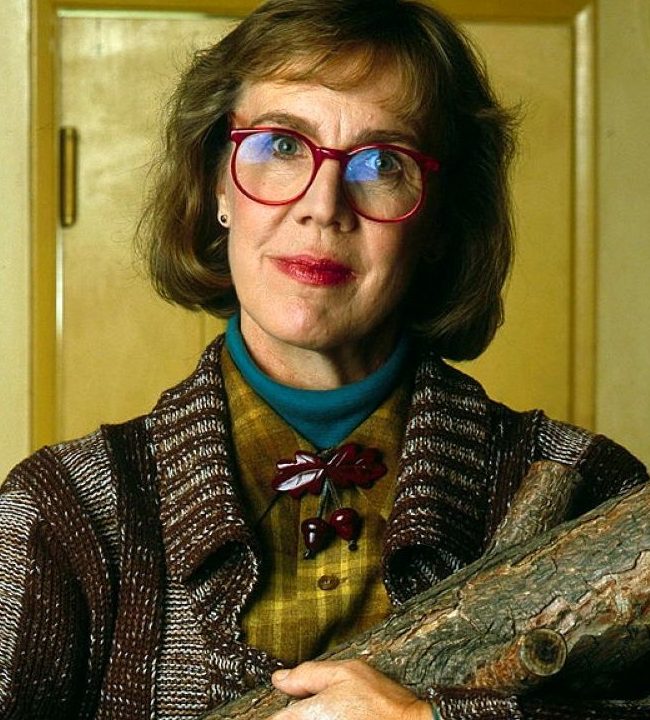

Maria Onetto is Veronica, a beautiful, wealthy Argentinian dentist who, one afternoon, runs over something with her car on an abandoned road and subsequently begins to act like she was the one the one who was hit. In her rearview mirror, we catch a glimpse of the object—a dog, not a boy, we see this—but as Veronica continues to worry and Martel begins to stir dangerous hints into the mix, one wonders if this shot was actually a moment of wishful thinking on Veronica’s part in which we were actually viewing the world through her own warped perspective. Over the course of the next week, Veronica exists in a state of paralysis, unable to do much, if anything, fully dependent on those around her—family, friends, and especially the much poorer house help—to do her work for her.

Maria Onetto is Veronica, a beautiful, wealthy Argentinian dentist who, one afternoon, runs over something with her car on an abandoned road and subsequently begins to act like she was the one the one who was hit. In her rearview mirror, we catch a glimpse of the object—a dog, not a boy, we see this—but as Veronica continues to worry and Martel begins to stir dangerous hints into the mix, one wonders if this shot was actually a moment of wishful thinking on Veronica’s part in which we were actually viewing the world through her own warped perspective. Over the course of the next week, Veronica exists in a state of paralysis, unable to do much, if anything, fully dependent on those around her—family, friends, and especially the much poorer house help—to do her work for her.

Whatever one thinks of The Headless Woman, that opening scene cannot be denied. It’s a masterpiece of tension, shot predominantly in shallow focus extreme close-ups by Barbara Alvarez and tautly edited by Miguel Schverdfinger, whose cross cutting between a group of adolescent boys (dark-skinned and poor) playing on the side of the road and Veronica driving in a distracted state, make us feel the impending accident. When it happens, Martel quiets the soundtrack and holds on an extended shot as a powerful rainstorm arrives, another symbol in a film that is loaded with them.

Unfolding at a somnambulistic pace, The Headless Woman plays like a Post Traumatic Stress Thriller, a Narco Mystery, or an Extremely Arid Satire. It’s obvious that Martel is commenting on the harsh class divide that plagues Argentina, but adding the mystery element to her film complicates matters and makes the constant obscuring of peripheral characters—namely, the poor, “insignificant” help—less of a political maneuver and more of a personal one, as this blurry state appears to be a direct response to the accident itself. Or is it supposed to speak of a more permanent fogginess when it comes to Veronica’s dealings with the underclass?

It might be a stretch to compare The Headless Woman to David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, but in trying to pinpoint why Martel’s film left me feeling so empty, it might actually explain something. Both films are atmospheric mysteries that place us inside the minds of troubled (artificially) blonde women using lush cinematography and haunting sound design (and which are admitted nudges to Vertigo). Yet whereas Lynch is reaching into his stomach and delivering something that, however “illogical,” still throbs with heartfelt emotion, Martel is critical of her characters to the point of draining her story of even the tiniest drop of feeling. And while I realize that Martel and Lynch are doing completely different things—a clear case of apples and tow trucks—I still can’t shake the feeling that while watching The Headless Woman, I’m never quite “getting it” or am “missing something.”

— Michael Tully