(Julia opened Friday, May 8th, in New York City and Los Angeles. It is now available on home video. Buy the DVD at Amazon, and visit the film’s official page at Magnolia Pictures to learn more.)

About two years ago, I had written off Erick Zonca as a casualty of the film business. The director of the seminal The Dreamlife Of Angels, a film that still towers over much of the “social realist” cinema that thrives on art house screens today, Zonca’s career was stalled by seemingly interminable financing problems for his projects. Then, as if from out of the blue, Zonca unleashed Julia on an unsuspecting Berlinale last year, instantly dividing audiences and critics who were not prepared for the director’s gritty vision. In this day and age, American moviegoers might have seen this coming; Julia was released overseas last spring but languished for months here in the USA before Magnolia Pictures picked the film up during Toronto with little fanfare and, recognizing its greatness, prepared it for its impending May 8 theatrical release. Buckle up.

Building on his work in Seule (Alone) and Le Petit Voleur (The Little Thief), two great and tragically underseen films from the late 1990s, Julia marks Zonca’s return to the life of the petty criminal. But while most critics have fixated on comparisons to John Cassavetes’ Gloria and The Killing Of A Chinese Bookie (influences which are certainly there), it is clear that Zonca is following through on themes that have always existed in his work, from the botched robbery of a taxi cab in his own “girl and a gun” short Seule, to the violent culture of criminal ambition in Le Petit Voleur, through to the tragic consequences of class ambition in The Dreamlife of Angels. In all of Zonca’s films, economic circumstances drive our protagonists into acts of violence and cultures of crime for which they are wholly unprepared, and so it is with Julia Harris (Tilda Swinton), a lower-level corporate drone and major league drinker who loses her job when her alcoholism gets in the way of her work.

When her neighbor offers to bring Julia into a kidnapping scheme with a guaranteed payday, a life spent among the big talkers and barstool hustlers at the local dive is suddenly transformed into action; Julia decides on a double cross and soon, in over her head and now responsible for the safety of Tom, the small boy she’s kidnapped, she heads down to Mexico to get the heat off of her back. But Julia can’t escape herself or her own shortcomings; a night of revelry among the locals turns into a tragic miscalculation and, instead of cutting and running, Julia must confront her own sense of responsibility and needs in order to make things right.

When her neighbor offers to bring Julia into a kidnapping scheme with a guaranteed payday, a life spent among the big talkers and barstool hustlers at the local dive is suddenly transformed into action; Julia decides on a double cross and soon, in over her head and now responsible for the safety of Tom, the small boy she’s kidnapped, she heads down to Mexico to get the heat off of her back. But Julia can’t escape herself or her own shortcomings; a night of revelry among the locals turns into a tragic miscalculation and, instead of cutting and running, Julia must confront her own sense of responsibility and needs in order to make things right.

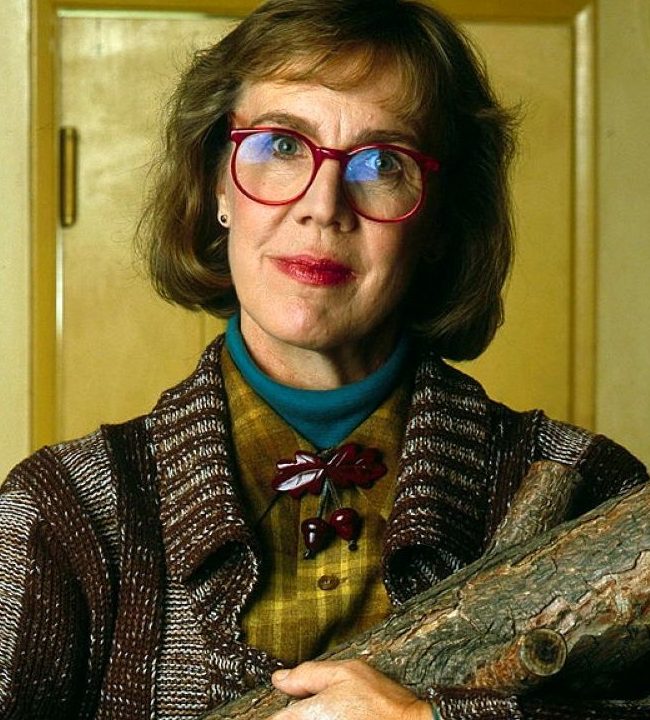

Is there anyone working in front of a camera lens today that has more courage than Tilda Swinton? Swinton has been a fixture on art house screens the past few years, living on Hollywood paychecks to fund a whirlwind mission to work with some of the most compelling filmmakers in the world. And while that has meant supporting roles with filmmakers as diverse as Béla Tarr, Andrew Adamson, Jim Jarmusch and David Fincher, there is not a frame of Julia that is not totally alight with Swinton’s provocative and moving performance. The hot-breathed, terrifying desperation that she brought to her Oscar-winning performance as Karen Crowder in Michael Clayton is on full display here, but tempered with a boozy naiveté that is both frustrating and heartbreaking, moving and deeply troubling. It is by far her juiciest role and Swinton responds to the opportunity with a brilliant performance that I still cannot get out of my head.

That Julia herself, this unlovable drunkard, is so compelling is testament to both Swinton and Zonca; it is their harmonious collaboration that keeps the tension pulsating. Zonca’s film has the look of a permanent hangover (grainy and bright, the dimly lit bars and interiors the only respite from the torment of the sunlight) but it moves with tremendous dexterity and purpose, twisting and turning, bringing Julia and the audience into the full realization of her character, never letting up until the flaring lights of anonymous cars pass gently by, without comment or recognition.

— Tom Hall