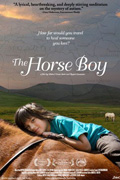

NOTE: After being bought, the film’s title was changed from Over the Hills and Far Away to The Horse Boy. We have updated Pamela Cohn’s original review to reflect this change.

NOTE: After being bought, the film’s title was changed from Over the Hills and Far Away to The Horse Boy. We have updated Pamela Cohn’s original review to reflect this change.

(The Horse Boy is distributed by Zeitgeist Films. It opened at the IFC Center on Wednesday, September 30th, 2009, and is now available on DVD. Visit the film and book’s official website for more detailed information.)

I’m going to preface this review by revealing that I have a gorgeous little cousin, intelligent, sweet and very, very funny—an adorable and loving child. She was diagnosed with autism at the age of three. So, needless to say, sitting and watching Michel Orion Scott’s The Horse Boy was a resonant, and highly emotional, experience for me in many ways. To say that this nonfiction film surpasses your average “case study of an affliction” flick would be a gross understatement, for it is both a thrillingly cinematic and rollicking adventure story, as well as an intimate journey into a family’s most private and tormented moments.

Director and cinematographer Scott, and producer, author, and activist Rupert Issacson, both reside in Texas: Scott in Austin and Issacson in nearby Elgin, where he has a horse farm. They came together over a mutual passion for studying, documenting and understanding the world through a connection with indigenous, tribal cultures around the world. Both men possess a desire to connect with humanity by going to the source. And this is exactly what they do when they travel to Mongolia in search of a powerful shaman to heal Issacson’s son, Rowan, an autistic boy who has an inexplicably profound connection with the animal world.

The film, narrated with humor and fervent transparency by Issacson, is graceful, fluid, and transcendent, both in its storytelling and in its cinematic language. It obviously speaks to Scott’s background in dance in the way he moves his camera, placing himself in the center of an emotional maelstrom, waiting patiently for the impending miracle which may—or may not—happen. The miracle, however, is not the literal one that takes place between the boy and the shaman; it is the miracle of the connection with the unseen world around us. And our guide into that world is the boy, Rowan. As he works his way towards the universe the rest of us inhabit, we work our way into his, alongside his mother and father.

What we learn from the various experts interspersed throughout the film is that autism, whether labeled so or not, has always been with us, and that we should be grateful for that. As Temple Grandin, a brilliant animal scientist and an autistic herself, explains, our world would not have any of its amazing inventions without the people who traverse this kind of internal universe. As researchers, clinicians, psychologists, and other experts parse the ways and means of this “affliction,” and how we can cope with those so “afflicted,” the theories of the whys and wherefores only seem to multiply, the mysteries only to deepen. This story, infused with raucous humor, deep pathos and brutal honesty, allows the magic of miracles to stand on their own and we find that we really don’t need any other explanation than that of a loving family searching for some peace and connection between themselves and their child. The various ways in which they get there are a sight to behold. And it all starts with a horse named Betsy.

What we learn from the various experts interspersed throughout the film is that autism, whether labeled so or not, has always been with us, and that we should be grateful for that. As Temple Grandin, a brilliant animal scientist and an autistic herself, explains, our world would not have any of its amazing inventions without the people who traverse this kind of internal universe. As researchers, clinicians, psychologists, and other experts parse the ways and means of this “affliction,” and how we can cope with those so “afflicted,” the theories of the whys and wherefores only seem to multiply, the mysteries only to deepen. This story, infused with raucous humor, deep pathos and brutal honesty, allows the magic of miracles to stand on their own and we find that we really don’t need any other explanation than that of a loving family searching for some peace and connection between themselves and their child. The various ways in which they get there are a sight to behold. And it all starts with a horse named Betsy.

In that same year when Rupert and his wife, Kristin, a wise and serene psychology professor, are trying to deal with, and find solutions for, Rowan’s violent displays of psychic pain, an extraordinary thing occurs when Rupert notices unusual behaviors in his horse, Betsy: she displays submissive body language towards the boy whenever he wanders into her pasture, limbs flailing, wailing loudly in an incomprehensible babble. (If you’ve ever been around horses, you would know that they do spook quite easily.) When Rupert puts the boy up on the mare’s back, Rowan immediately becomes blissfully calm and, astoundingly, begins to talk in full sentences, where before he could only scream and cry and stutter.

Also in that same year, as part of his human rights work, Rupert brings some San Bushman hunter-gatherers from Southern Africa to America to speak out about the loss of their land to diamond mining. Rowan and Kristin both went along on this journey, joining a gathering of healers, elders and shamans from around the world. While there, some of the healers brought the small boy into their ceremonies and his autistic symptoms began to fall away. His father, desperate to reach his son, then starts to brainstorm about where there might be a place where both horses and shamanic healing are culturally intertwined. That’s how they get to their journey in Mongolia, traversing the Steppe and forests for several days on horseback to where one of the most powerful healers in the world dwells—among the Reindeer People. And it is, truly, a magical place: calm, gentle, and located smack up against the heavens.

The Horse Boy chronicles their journey, simultaneously delving into the mysterious worlds of autism, the relationship between humans and animals, and the relationships between seemingly disparate cultures. Scott, along with editor Rita K. Sanders, cameraman Jeremy Bailey, sound recordist Justin Hennard, and musicians Lili Haydn and Kim Carroll, bring together a richness and emotional heft to this already heady piece. What could have been an overwrought soap opera instead displays a calm transcendence that is very much in line with the dignity and serenity of the Mongolian people, and also the openness of Rupert and Kristin and Rowan as they find their way into one another’s separate worlds to form a singular one of their own.

— Pamela Cohn

(One final note: there is a companion book called The Horse Boy, A Father’s Quest to Heal His Son written by Rupert Isaccson, currently only available in the UK. It will be available in North America by Little Brown, Spring 2009, released internationally, Summer/Fall 2009.)