(Invisible Girlfriend is now out on DVD through David Redmon and Ashley Sabin’s homegrown label, Carnivalesque Films. Buy it there, or at Amazon.)

(Invisible Girlfriend is now out on DVD through David Redmon and Ashley Sabin’s homegrown label, Carnivalesque Films. Buy it there, or at Amazon.)

The first time I saw David Redmon and Ashley Sabin’s Invisible Girlfriend, until the film reached its truly unbelievable sideswipe of a climax (and by that I mean literally not believable), I simply thought Redmon and Sabin were doing what they do best: shining their nonjudgmental light on another marginalized figure who would almost certainly be used as a preaching point in the hands of a more pompously misguided director. Whether revealing the humbling love between a young Mexican family (Intimidad) or chronicling the efforts of a New Orleans couple to shelter homeless residents in a post-Katrina New Orleans backyard (Kamp Katrina), Redmon and Sabin have a special knack for embedding themselves fully in complicated environments, removing even the tiniest political and sociological shards, and delivering bracingly intimate portraits that respire with pure, unfiltered humanity.

But here comes Invisible Girlfriend and that devastating climax, with a narrative twist so implausible that it would feel forced and phony in even the most convincing of fictional features. When that moment arrives, Redmon and Sabin’s latest transforms itself into something altogether different, a documentary film that has more of a spiritual kinship with the most celebrated Southern literature (William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, John Kennedy Toole, Carson McCullers). Shot on a consumer-based DV camera, it nonetheless features startlingly vibrant cinematography and is loaded with symbols that didn’t fully reveal themselves to this viewer until a third go ‘round (sparking the immediate desire for a fourth), buzzing with the bizarre, almost supernatural energy that is coursing through the bloodstream of the Deep American South. In the process, it raises some heavy questions about faith, sanity, dreams, and the cruel hand of fate.

To describe the plot of Invisible Girlfriend is to make it sound like a riff on The Wizard of Oz written by a children’s book author with an extremely dark edge . In many ways, that’s exactly what it is, for this story is indeed the stuff of strange fairytales (the only difference being that it is 100% real). Charles Filhiol, a man suffering from schizophrenia, lives with his parents and children in the small Louisiana town of Monroe. Charles has a girlfriend, only as he explains it to a couple along the way: “My girlfriend has a complexion problem. She has no complexion.” Charles’ girlfriend is none other than Joan of Arc. Yet though he considers Joanie to be his one true love, he believes that a kindhearted New Orleans bartender, Dee Dee, might be the earthly, physical representation of that love. In order to find out if this is, in fact, the case, Charles hops on a bright red bicycle and starts pedaling on a 400-mile journey, through a hauntingly ravishing Louisiana landscape, to rendezvous with Dee Dee in New Orleans.

To describe the plot of Invisible Girlfriend is to make it sound like a riff on The Wizard of Oz written by a children’s book author with an extremely dark edge . In many ways, that’s exactly what it is, for this story is indeed the stuff of strange fairytales (the only difference being that it is 100% real). Charles Filhiol, a man suffering from schizophrenia, lives with his parents and children in the small Louisiana town of Monroe. Charles has a girlfriend, only as he explains it to a couple along the way: “My girlfriend has a complexion problem. She has no complexion.” Charles’ girlfriend is none other than Joan of Arc. Yet though he considers Joanie to be his one true love, he believes that a kindhearted New Orleans bartender, Dee Dee, might be the earthly, physical representation of that love. In order to find out if this is, in fact, the case, Charles hops on a bright red bicycle and starts pedaling on a 400-mile journey, through a hauntingly ravishing Louisiana landscape, to rendezvous with Dee Dee in New Orleans.

Redmon and Sabin establish Charles’ condition at the outset by presenting him years earlier, in Kamp Katrina-era New Orleans (Charles plays a minor, but memorable, role in that film), in what appears to be a manic state, as he plays catch with a ball at the Maid of Orleans statue, explaining how and when this relationship was born. We then quickly return to present day Monroe and see a much more seemingly stable Charles in a much more seemingly stable environment. His mother explains that Charles was diagnosed by one doctor as a bipolar schizophrenic; his father doesn’t remember the technical jargon, but says that Joanie appeared six years ago; and his adolescent son hilariously and sweetly acknowledges that his dad is kooky but also great. The tears he sheds when Charles is about to leave shows just how great he thinks he is. Perhaps most importantly, the filmmakers allow Charles to speak from his own ferociously first-person perspective. It’s a credit to their uncritical approach that at times Charles’ statements seem so insightful and sane that it made me wonder about just how “sick” he actually was. This hands-off approach to mental illness allows us to immerse ourselves in a journey that, on all rational grounds, is an inarguably ridiculous, cockeyed venture.

Along the way, Charles encounters many different individuals, who express amused disbelief at his crazy mission but welcome him (and the filmmakers) into their homes nonetheless. The highlight of these encounters—not to mention the most subtly brilliant—takes place at a house where Charles stops to admire a small tin man that’s hanging from a wire on a the front fence. When the old man who lives there comes out to investigate, he reveals himself to be an absolute kook, calling Dorothy “Mildrew” and when corrected by Charles, says, “Dorothy? That bitch. Boy she makes me mad. Hoo!” Later, after eating shrimp cakes, Charles sits down at the kitchen table to talk to the woman. When she asks him about his girlfriend and Charles explains that she’s invisible, this causes a moment of cringe-worthy discomfort for a viewer. Yet her response is another sideswipe: she casually informs Charles that her daughter is a witch. On the surface, this scene is a humorous, sweet-natured interplay between two kindly strangers. But subconsciously, it does something deeper: it makes Charles seem normal and sane.

Visually, the film is swimming with symbols. On a first viewing, these images might feel like spicy ingredients tossed into Redmon and Sabin’s pot of gumbo to add flavor. But after a second or third viewing, when one has the foresight of that too-impossible-to-believe ending, these moments attain a mystical weight. A cow struggling to give birth to a posterior set calf, freshly killed animals on the side of the road, a museum dedicated to the memory of fallen American soldiers, water in many permutations. Again, it’s a credit to Redmon and Sabin’s unforced presentation that one might not grasp these hidden signs until the film has ended, that we simply think we’re taking a breezy ride. If only that were the case.

It’s offensive to me as a supporter of groundbreaking, genre-transcending cinema that Invisible Girlfriend didn’t receive its proper due—and I’m just talking about with regards to the piddly film festival circuit. The more discomfiting realization is that what I find to be so exhilarating about Invisible Girlfriend is what will most likely make many people dismiss it. The film takes Charles at his word and doesn’t probe his schizophrenic condition more deeply (i.e., thank God). The filmmakers don’t insert themselves into the story, raising ethical questions for some viewers about a filmmaker’s responsibility to his subject (i.e., get over it). Redmon and Sabin don’t hit us over the head with their film’s loaded symbolism, allowing us to put the pieces together in whatever fashion we see fit (i.e., hallelujah). I would go so far as to say that in American cinema of the very moment, David Redmon and Ashley Sabin are coming the closest to achieving Werner Herzog’s state of “ecstatic truth.” You won’t believe Invisible Girlfriend when you see it for a first time, and you’ll believe it even less when you see it again. It’s one of 2009’s most remarkable films.

— Michael Tully

Pingback: Hammer to Nail » Blog Archive » NORWEGIAN DOCUMENTARY FILM FESTIVAL 2010

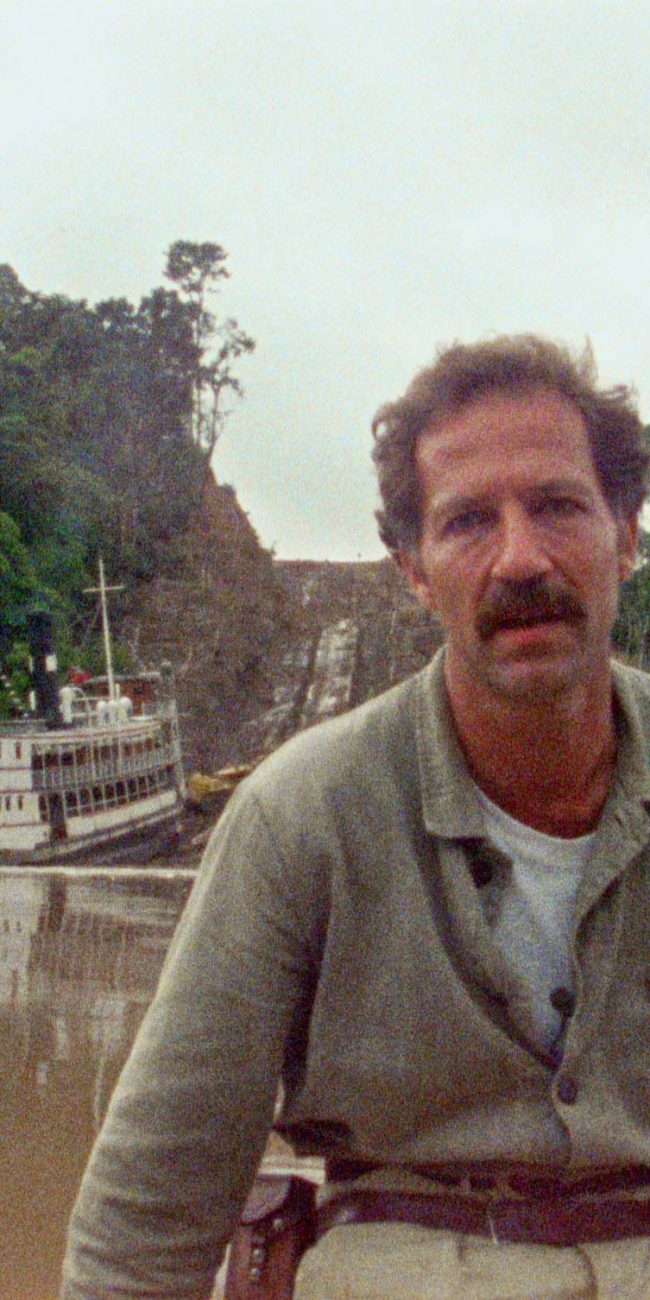

Charles Filhiol

What a wonderful review! How did I miss this one before? You get it, Mr. Tully. You truly do.