As a primer for those unfamiliar with the work of Austria’s other cinematic provocateur (no, not you, Mr. Haneke), Anthology Film Archives has assembled a weeklong mini-retrospective—The Films of Ulrich Seidl (July 24-30, 2009)—that will culminate with the New York City theatrical run of Seidl’s Import/Export on July 31st. In preparing to write this piece, I held a Seidl mini-retrospective of my own over the course of a long weekend. I emerged on the other side, smeared with grease and caked in dirt, craving a steaming hot shower—both literal and metaphorical—and worrying that Seidl had permanently scarred my opinion of that nook of the world.

These films aren’t for everyone. Case in point: I would call myself an admirer and I’m not sure they’re for me. With a tar-blackly comical spirit, Seidl depicts a modern universe that is bleak, crude, confrontational, mundane, explicit, and bracingly real. This content will surely be easier to swallow for some, but even taking that into account, one must give credit where credit is due. For Seidl doesn’t just blur the line between documentary and narrative. He erases it. He does this so confoundingly well, in fact, that the question of “is it fact or fiction?” becomes utterly irrelevant when discussing his work. While many filmmakers also toe this line, no one does it with nearly quite the same subtly demonic gusto.

Though he is greatly interested in the line between Eastern and Western Europe and how that invisible divide manages to maintain such rigid cultural differences, Seidl’s overarching directorial mission is to present a nearly hellish vision of modern life at its most grotesquely mundane. Rather than setting up more traditionally artificial climaxes and confrontations, he chooses instead to depict scenes from everyday life—some dramatic, most not—in which characters resort to depraved behavior out of what appears to be either boredom or a historically ingrained sense of purposelessness. If this all sounds pretentious and punishing, it isn’t. For Seidl’s ace in the whole is his acerbic sense of humor, which keeps his films from tumbling down a drain of complete and utter hopelessness (though for many, this splash of irreverence will only add to the distaste).

Though he is greatly interested in the line between Eastern and Western Europe and how that invisible divide manages to maintain such rigid cultural differences, Seidl’s overarching directorial mission is to present a nearly hellish vision of modern life at its most grotesquely mundane. Rather than setting up more traditionally artificial climaxes and confrontations, he chooses instead to depict scenes from everyday life—some dramatic, most not—in which characters resort to depraved behavior out of what appears to be either boredom or a historically ingrained sense of purposelessness. If this all sounds pretentious and punishing, it isn’t. For Seidl’s ace in the whole is his acerbic sense of humor, which keeps his films from tumbling down a drain of complete and utter hopelessness (though for many, this splash of irreverence will only add to the distaste).

Taking all of that into account, it seems impossible to say this, but it’s true: Ulrich Seidl is a humanist. His work is more Dostoevsky than Von Trier. For as punishing and cruel as many of his scenes get, there exists a feeling that he isn’t out to simply punish viewers and make them feel miserable. He’s out to elicit a reaction, yes, but he appears to be more jovially amused his characters than anything else (he certainly doesn’t hate them). Watching these films, with their strange mix of the stylized and hyper-realistic, the sorrowful and the humorous, one cannot deny Seidl’s rightful place in the upper tiers of the world cinema canon.

Here, in order of production year, are the films screening at Anthology this week:

Losses Are To Be Expected (1992) — (Unseen by me.)

Animal Love (1995) — Fellow fiction/nonfiction line mutilator Werner Herzog is famously quoted on the DVD box cover for this film saying: “Never have I looked so directly into hell.” He’s right. Animal Love features Seidl’s now signature style of inserting portraiture-like chapter breaks of subjects staring into the camera within his film’s casually unfolding “narrative”. In Animal Love, that narrative consists of watching several different pet owners trudge through their increasingly dour daily lives. At the beginning, even for someone familiar with Seidl’s work, one might innocently mistake this for a sweet-natured tribute to humans and their pets. Yeah, right. It isn’t long before Seidl’s disturbing reality emerges. When I think back on Animal Love, a nightmarish image springs to mind: a dingy room jam-packed with the film’s subjects—both humans and animals—all piled on top of one another, engaged in an obscenely disgusting orgy. Though this image never actually occurs in the film, it’s the best way I can describe how Animal Love made me feel. You have been warned.

Animal Love (1995) — Fellow fiction/nonfiction line mutilator Werner Herzog is famously quoted on the DVD box cover for this film saying: “Never have I looked so directly into hell.” He’s right. Animal Love features Seidl’s now signature style of inserting portraiture-like chapter breaks of subjects staring into the camera within his film’s casually unfolding “narrative”. In Animal Love, that narrative consists of watching several different pet owners trudge through their increasingly dour daily lives. At the beginning, even for someone familiar with Seidl’s work, one might innocently mistake this for a sweet-natured tribute to humans and their pets. Yeah, right. It isn’t long before Seidl’s disturbing reality emerges. When I think back on Animal Love, a nightmarish image springs to mind: a dingy room jam-packed with the film’s subjects—both humans and animals—all piled on top of one another, engaged in an obscenely disgusting orgy. Though this image never actually occurs in the film, it’s the best way I can describe how Animal Love made me feel. You have been warned.

Pictures At An Exhibition (1996)/The Bosom Friend (1997) (Unseen by me.)

Models (1998) — The modeling industry is disgusting enough as it is. The idea of Seidl focusing on it for an entire feature sounds like a dangerous proposition (as in: two dirties makes a way too dirty?). Though he doesn’t pull any punches in exposing the more repulsive aspects of this lifestyle, Seidl’s particular brand of artistry produces something fascinating nonetheless (kind of like watching a pretty girl projectile vomit). Models follows a gaggle of young women who suffer through an excruciating routine of fashion shoots, nighttime debauchery, morning recovery, more fashion shoots, and much more nighttime debauchery. Cocaine, bulimia, sleeping with sleazy photographers, smoking, drinking, contemplating liposuction, considering boob and lip injections, cheesy European club music… don’t worry, it’s all here. By the time the credits roll, you might want to enter rehab yourself.

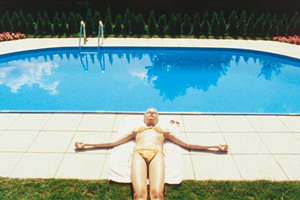

Dog Days (2001) — Dog Days is widely regarded as Seidl’s first true fictional feature, but to my eyes, its approach is utterly indistinguishable from Models and Animal Love. Whatever the case, this film finds Seidl abandoning the purgatorial winter for the more literally hellish summer (he even went so far as to only shoot above a certain temperature over the course of three years to make things even hotter). Seidl retains his pattern of following several characters over the course of a few days, not worrying about crossing paths along the way (though some do). Characters include: a mildly retarded woman who hitches rides from strangers, only to drive them mad with her constant asking of inappropriately personal questions; a grieving couple who still live together but who don’t speak to one another as the woman embarks on a series of relentless sexual escapades; an abused woman whose husband’s friend feels remorse for brutalizing her one night so he decides to abuse her husband instead; a traveling security system salesman whose desire to quiet his clients leads him to commit a very cruel act of deception; and a young girl whose boyfriend’s jealously ruins their relationship. Dog Days plays like an Austrian variation on American Beauty, minus the Hollywood cheese and infused with a sense of grimy artistry that makes it impossible to ignore.

Dog Days (2001) — Dog Days is widely regarded as Seidl’s first true fictional feature, but to my eyes, its approach is utterly indistinguishable from Models and Animal Love. Whatever the case, this film finds Seidl abandoning the purgatorial winter for the more literally hellish summer (he even went so far as to only shoot above a certain temperature over the course of three years to make things even hotter). Seidl retains his pattern of following several characters over the course of a few days, not worrying about crossing paths along the way (though some do). Characters include: a mildly retarded woman who hitches rides from strangers, only to drive them mad with her constant asking of inappropriately personal questions; a grieving couple who still live together but who don’t speak to one another as the woman embarks on a series of relentless sexual escapades; an abused woman whose husband’s friend feels remorse for brutalizing her one night so he decides to abuse her husband instead; a traveling security system salesman whose desire to quiet his clients leads him to commit a very cruel act of deception; and a young girl whose boyfriend’s jealously ruins their relationship. Dog Days plays like an Austrian variation on American Beauty, minus the Hollywood cheese and infused with a sense of grimy artistry that makes it impossible to ignore.

Jesus, You Know (2003) — This film is pretty much guaranteed to elicit passionate reactions from viewers on both sides of the religious divide. Seidl’s ingenious premise is to film individuals praying aloud to Jesus, confessing their innermost wants and desires. As we listen to each new confessor, the whole thing starts to sound like these people are talking to Santa Claus or gossiping with their best friends. After a while, though, I started to question Seidl’s mission. I wish he had found at least one person who actually had nothing to complain about, who was simply thankful for their life and attended church for purely spiritual reasons. Though I guess that wasn’t his point. Still, hearing these distorted minds express themselves with such embarrassing candor didn’t make me critical of religion. It made me critical of these poor, sad people.

— Michael Tully