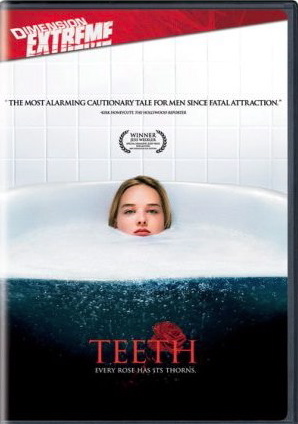

(Buy Teeth at Amazon.)

In the movies, there is no more dangerous balance to strike than between comedy and horror. One false step in the direction of camp and the ability to truly frighten the audience is sacrificed. Too heavy-handed with the horror and any comic touches will seem completely out of context. When the balance is just right, horror and humor are a near-perfect delivery mechanism for social criticism; laughter can be a wonderful companion for nail-biting fear. Mitchell Lichtenstein’s Teeth, recently released on DVD by Dimension Films, is a case study for the triumph of balance, a darkly comic story that strikes a primal chord in the most private of places.

Dawn (Jess Weixler) is your typical suburban teenager; raised in the shadow of the local nuclear power plant, her high school dream is to fall in love, get married and break her vow of abstinence with the man of her dreams. But the suburbs have a different plan for Dawn. After heading down to the local watering hole with her dashing boyfriend Tobey (Hale Appleman), one thing leads to another and soon, against her will, Dawn finds herself in the grips of one of the great, tragic (and, in reality, far too frequent) nightmares of American girlhood; Tobey won’t take no for an answer and rapes Dawn under the waterfall.

But Dawn, alienated from her own body because, the film implies, of her obsession with her own sexual innocence, is by no means powerless in the moment; her vagina takes control and, using a long dormant set of vagina dentata (or internal vaginal teeth), castrates Tobey in the middle of his crime. Lichtenstein handles the moment with an almost unbelievable sense of humor and horror; using a series of close ups of the teenagers faces and their bodies, he delivers Dawn’s knockout bite with the righteous justice of female vengeance and sexual power set loose from a Pandora’s box. But just when the power of the moment threatens to shift empathy from the victim of a sexual crime to the mortally wounded jerk who perpetrated it, Lichtenstein cuts to the castrated penis itself, dismembered, lying on the ground as a crab (a wicked pun in and of itself) threatens to carry it away. In this moment, an entire theater full of men will inevitably cross their legs and women will snicker with a little tinge of satisfaction. The genre conventions of sexual power, so often geared toward male sexual fantasy, get an instant reversal that cuts to the bone.

Body horror and castration fears are not new to the horror genre; low-budget exploitation films like I Spit On Your Grave have always shared the video store shelf with the work of masters like David Cronenberg (who always seems willing to stick an oozing, semi-organic device under the skin of his characters). What separates Teeth from these obvious predecessors is Lichtenstein’s masterful balance of tone, complimented by Jess Weixler’s fearless portrayal of Dawn. As Dawn grows in experience, she begins to harness and understand her body’s power, becoming an avenging angel who metes out punishment to everyone from her obnoxious gynecologist to Brad (a creepy John Hensley), her nasty little asshole of a step-brother. Weixler captures every mode of Dawn’s empowerment from naïve school-girl to sexually aware young woman with the same sense of bewilderment and horror that the ripples through the audience. As Lichtenstein builds toward his bloody finale, Weixler keeps the story on a knife’s edge with her uncanny ability to marry innocence and murderous intent in a single, unforgiving twitch of her pursed lips.

Body horror and castration fears are not new to the horror genre; low-budget exploitation films like I Spit On Your Grave have always shared the video store shelf with the work of masters like David Cronenberg (who always seems willing to stick an oozing, semi-organic device under the skin of his characters). What separates Teeth from these obvious predecessors is Lichtenstein’s masterful balance of tone, complimented by Jess Weixler’s fearless portrayal of Dawn. As Dawn grows in experience, she begins to harness and understand her body’s power, becoming an avenging angel who metes out punishment to everyone from her obnoxious gynecologist to Brad (a creepy John Hensley), her nasty little asshole of a step-brother. Weixler captures every mode of Dawn’s empowerment from naïve school-girl to sexually aware young woman with the same sense of bewilderment and horror that the ripples through the audience. As Lichtenstein builds toward his bloody finale, Weixler keeps the story on a knife’s edge with her uncanny ability to marry innocence and murderous intent in a single, unforgiving twitch of her pursed lips.

Teenage girls have never had it easy in horror films; the sexually available teenage girl as defacto victim is one of the genre’s most dependable (and troubling) tropes. But as films like Teeth and the Ginger Snaps series continue to show, the terrors of female adolescence are fertile ground for revolutionizing the genre. Killers, once a source of existential dread, become justified, even empathetic, in the adolescent moment; bodies are changing, hormones are running wild and the fresh, bloody uncertainty of fertility provides a window into understanding deadly motivations. Couple that change with a character like Dawn’s obvious victimization at the hands of greedy, dirty young men and you have built-in empathy for what would otherwise be unconscionable. There is a profound intelligence behind Teeth, a sense that American values are a source of deep denial about the power of female sexuality and the film’s winking pleasures are to be found in Lichtenstein’s ability to put the audience squarely on Dawn’s side, against their own potentially hypocritical self-interest. But while Lichtenstein’s argument in favor of female power is clear, Teeth is never didactic; it’s a movie with blood on its hands and a delicious twinkle in its eye.

— Tom Hall