BEST WORST MOVIE / TROLL 2

(Best Worst Movie is now available on DVD through New Video Group. For those of you anywhere on Earth with a connection to the internet—if you’re reading this, that is—you can watch Troll 2 for free on Hulu right now.)

I might as well begin with the story of when I experienced Troll 2 for the very first time. Rather than having stumbled upon it myself, I was shown the light by a generous group of already converted worshippers. The year was 1995. The season was spring. I was visiting my sister at her college in Salisbury, Maryland, where I had befriended her male neighbors, who listened to pop punk, drank malt liquor, and watched endless hours of useless television. Sitting on the front porch during a Sunday afternoon thundershower, our discussion turned to cinema. We rattled off our personal favorites, a who’s who of independent films and ’70s classics, but eventually they stumped me when one of them said Troll 2. My confused reaction caused Dave, the spirited leader, to grab me by my shirt collar (yes, literally), drag me off the porch into the rain, and hurriedly drive us to the nearest video store, where Troll 2 awaited us.

Returning home, the lights were dimmed, the rain began to fall more steadily, and the alcohol began to flow more profusely. Ninety-four minutes and thirty-three seconds later (well, actually it was probably another twenty-five minutes after that, taking into account the necessary pauses, rewinds, and re-rewinds), my life was forever altered. No longer did I think the same way when processing and critiquing films. My previous conception of the world shattered and I began to see things in a new and different way. I felt like I had dropped an egregious amount of acid. I forgot how to spell my name.

For the next eighteen days, everything seemed like a dream. At work, at home, hanging out with friends, I couldn’t decide what was real, what was serious, and what was a morphed Troll 2-inspired delusion. I debated checking into a psychiatric hospital, but my ability to accomplish simple day-to-day tasks convinced me that this step wasn’t necessary. I would eventually snap out of it, and the world would once again return to its normal predictability. Eventually, it did, yet the memory of that initial viewing never fully faded; it continued to affect my every thought and action, however subtly. It still does.

The above three paragraphs are taken from the introduction of a book I began writing in 1998 called The Ethics of Troll 2. Although I only managed to complete a few chapters, my intentions were dead serious. This movie deserved to have a book written about it, as Troll 2 wasn’t a just a case of a movie being so bad it was good. Troll 2 was so bad it was uniquely, defiantly, utterly, indescribably, insanely, dangerously, exhilaratingly brilliant.

What is it about Troll 2 that makes it so “special” (in the inappropriate Special Olympics sense of the term, that is)? Let’s start with these two inconsistencies:

1) Check out the thumbnail image of the home video box cover above. It’s fine, right? A little cheesy but not terrible. The only problem with it is that that little boy and that monster have absolutely nothing to do with Troll 2. It’s like the cover for a different movie accidentally got shipped to the printer and the studio didn’t have enough time or money (or energy) to fix it.

2) The town that the Waits family journeys to, in a city-country home exchange, is called Nilbog, which if spelled backwards… doesn’t spell TROLL. Or to put it another way: the word troll is never uttered in a movie that happens to be called Troll 2 and is jam-packed with references to goblins.

A plot synopsis is in order:

The Waits’ are a typical, seemingly well-adjusted nuclear family: Dad, Mom, Holly, and Joshua. Holly is a pretty teenager whose boyfriend, Elliott, can’t crawl into bed with her without bringing his dopey buddies along. This is the source of major friction, as Holly wants to bring Elliott on vacation but he seriously can’t seem to abandon his buddies for five minutes, let alone a week (begin: unintentional yet screaming undercurrent of homoeroticism). Joshua is a whiny adolescent who is visited by his bearded—and dead—Grandpa Seth every night, to the disappointment of his disturbed (or is that disturbing?) mother. The dad, Michael, is a kind-natured gentleman who has organized a city-country exchange as a fun family adventure. He’s hopeful and optimistic, like a dumb American dad should be.

On the drive to Nilbog, Holly spots Elliott and his cronies in a broken down camper off the road (as in, wayyy too far off the road for her to see them). She’s now convinced that he mustn’t really love her—or, to put it more appropriately, that he really loves them. Joshua keeps whining because that is what Joshua does. His mother, Diana—who we are already suspect of due to her pin-eyed, Stepfordian delivery (note to first-timers: this is just bad acting, not foreshadowing of a darker revelation to come)—convinces Joshua to sing his favorite song, “Row Your Boat,” which sparks one of the more atonal, Caucasoidal family renditions that have ever graced the interior of a rolling minivan. At one point, Joshua spots Grandpa Seth on the side of the road and gets his parents to pull over by feigning vomiting. Turns out, Grandpa Seth is just a scary, bearded bum. (Or is he? Let the illogical, unanswerable questions begin to pile.)

Upon rolling into downtown Nilbog, the family is surprised to discover that it appears to be abandoned. Michael, the wise patriarch that he is, suggests that it’s because of the late hour that everything is so quiet and still (note: it’s broad daylight). When they finally arrive at the home of the Presents, a menacing family that consists of a similar four-person dynamic, Joshua notices strange tattoos on their necks and is concerned that all is not what it seems. Moments later, when the Presents leave and Joshua and family wander inside, they discover a spread of food. Mom, Dad, and Holly are thrilled. Joshua appears to be the only one who notices the goopy green mold covering everything. When Grandpa Seth appears to warn Joshua that if his family eats this food, they will be chewing their lives goodbye, he snaps his fingers and freezes time for thirty seconds to allow Joshua to figure out a way to prevent this from happening (note: when things get very harried later in the film, neither Grandpa Seth nor Joshua seem to remember that Grandpa Seth has this potentially verrry helpful trick in his arsenal). Joshua’s way of keeping them from eating is to… you know what, I should stop there.

One can explain what happens in Troll 2 and perhaps do justice to the insanity, but it truly must be seen to truly grasp the levels of cinematic dysfunction on display. What inspired me to want to write a legitimate book about it is that all of these problems—the script, the story, the acting, the special effects, the music—all congeal into such a strange goblet that one can help but want to drink thirstily from its richly abundant thematic and metaphorical liquids. The aforementioned homoeroticism, the undeniable anti-carnivorous/pro-vegetarian stance, a child’s inability to reconcile the death of a loved one, the city folks’ paranoia of small-town life… it’s all there. That all of these hearty issues are like the garnishes on a retarded sandwich only adds to the allure.

One can explain what happens in Troll 2 and perhaps do justice to the insanity, but it truly must be seen to truly grasp the levels of cinematic dysfunction on display. What inspired me to want to write a legitimate book about it is that all of these problems—the script, the story, the acting, the special effects, the music—all congeal into such a strange goblet that one can help but want to drink thirstily from its richly abundant thematic and metaphorical liquids. The aforementioned homoeroticism, the undeniable anti-carnivorous/pro-vegetarian stance, a child’s inability to reconcile the death of a loved one, the city folks’ paranoia of small-town life… it’s all there. That all of these hearty issues are like the garnishes on a retarded sandwich only adds to the allure.

At the time, I assumed my friends and I were the only ones who grasped the accidental genius that was Troll 2. Nobody else I knew ever talked about it. But thanks to the internet, I have come to learn that not only were we not alone in our devotion, but we were a part of something freakishly special. And thanks to Joshua himself, I now know how it all went so gloriously wrong.

Michael Stephenson’s Best Worst Movie is a remarkably thorough and engaging documentary that explains, in staggering detail, the Troll 2 phenomenon. So who is this Stephenson guy and why does he think it’s his duty to make the definitive film about Troll 2? How about this: he’s f-cking Joshua. Growing up the target of ridicule and shame, Stephenson gradually came to terms with his fate and turned his horrific negative into a genuine positive. I witnessed this at the film’s world premiere at the 2009 SXSW Film Festival. Even those who hadn’t seen Troll 2 were swept away by Best Worst Movie.

Some things are perhaps better left as unsolved mysteries (see: After Last Season), but after over a decade of watching and being utterly baffled by Troll 2, it comes as a real treat to see how it all went so gloriously wrong. I’m not lying when I confess to having seen Troll 2 as much as, or more than, any other movie that has ever been made. And I also wasn’t lying when I said that it made me approach cinema differently. I had my Troll 2 epiphany while in film school. During the week I watched movies by world cinema’s masters—Griffith, De Sica, Bergman, Kubrick—and on the weekend I returned to Salisbury and Troll 2 to study a different form of mastery. It really came down to this one loaded question, something I continue to contemplate to this day:

Which is a more miraculous feat to be studied, appreciated, and obsessed over: intentional or unintentional genius?

While Best Worst Movie might not answer that question, it at least answers an equally important personal one that I thought would plague me forever, which is: how in the hell did this happen? On the VHS box cover, the film’s director was listed as “Drago Floyd.” But it appeared in the film’s credits as “Drake Floyd.” Turns out, the director was an Italian named Claudio Fragasso, who wrote the film with Rossella Drudi. Automatically, this clarifies one of the film’s gaping problems, which is the head-cockingly strange dialogue. When one stops to consider that the script was written by non-English speakers who refused to let the actors deliver the lines in their own natural manners, well, one could call it a day right there.

But one can’t, because the insanity continues to pile. Next up is the acting. It turns out the dad, who was played by the congenial George Hardy, had dreams of becoming an actor before putting them to bed and settling into a life as a small-town dentist. On a lark, he answered a call and got the part. As for the mother, played by Margo Prey, those pin-headed eyes and robotic delivery didn’t lie. The most uncomfortable scene in Best Worst Movie is when Stephenson and Hardy show up at Prey’s home to try to convince her to drive with them to the Alamo Rolling Roadshow’s weekend long “Nilbog Invasion – The Troll 2 Celebration” in Utah in June of 2008. If Prey had a screw loose back in the ‘90s when the film was made, time has knocked loose the rest of them. This scene begins funny and turns very, very sad. Fortunately, Stephenson lets bygones be bygones and gets to the festivities of the weekend, when an arrogant Fragasso interrupts many of the panels by heckling his actors, who he refers to as dogs.

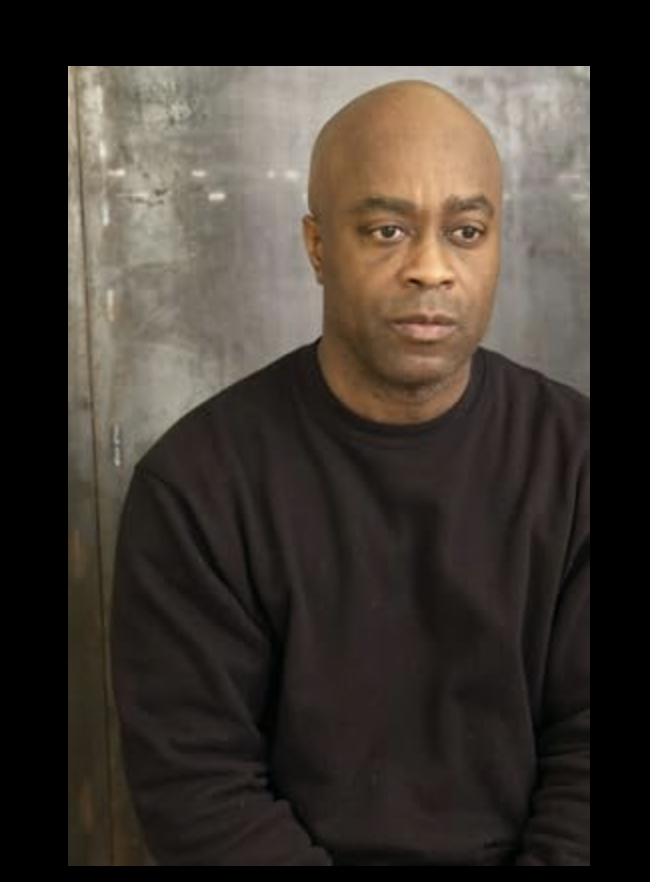

This casting magic is perhaps best exemplified by the portrayal of Nilbog’s shop owner by a terrifying man named Don Packard. Witness this:

Watching Troll 2, one can’t help but wonder: how could the leads be so catatonic and yet this peripheral character could deliver such a brief but unsettlingly creepy performance. In Best Worst Movie, Packard explains the situation that led to his being cast. He was in a mental institution and got out on weekends. One weekend, he auditioned. The next, he shot his scenes. As Packard refers to his own performance (this isn’t the exact quote), “That was not a sane man delivering those lines!” Once again, another mystery solved.

Best Worst Movie gleefully solves mystery after mystery for the initiated, but for those who are encountering it without any prior knowledge, it is worthy viewing nonetheless, as it explains how an under-the-radar work of pop garbage can become a genuinely world-renowned cultural phenomenon. It’s also an unexpectedly poignant portrait of a kind, sweet man—George Hardy—who is easily one of the most deserving accidental superstars that the cinema has produced.

Troll 2 is often referred to as the internet generation’s Rocky Horror Picture Show, and while there will always be new films that spark a similar fascination (After Last Season, The Room), what makes Troll 2 so special is that its myth was born as a grassroots phenomenon just before the internet had permeated the world. Further, as detailed by Stephenson in Best Worst Movie, while almost every movie has its flashes of ineptitude, Troll 2 takes the textbook of How To Make An Utterly Awful Movie and breaks all of those rules into a million glorious pieces. Against my better judgment, I would argue that the unintentional genius of Troll 2 is as rare, special, and astounding a force as The Birth of a Nation, as The Bicycle Thief, as Fanny and Alexander, as 2001.

— Michael Tully