BUTTER ON THE LATCH

(Distributed by Cinelicious Pics, Butter on the Latch releases theatrically and on VOD on Friday, November 14, 2014, as part of a double-bill with Thou Wast Mild and Lovely. It first screened publicly at the 2013 Maryland Film Festival before officially premiering at the 2014 Berlinale in the Forum section. Visit the film’s Facebook page and the Cinelicious site to learn more. NOTE: This review was first posted on February 12, 2014.)

Josephine Decker’s Butter on the Latch is a work of frayed edges and starkly showing seams. It wears its scant means and “do it yourself” aesthetic like a badge of honor, yet these inhibiting factors are completely ineffectual in restraining the ambition and artistry of Decker’s imagination. It’s loaded with ideas: nightmarish images, visceral, shocking cuts, explorations of female friendship, and probably most uniquely, a hypnotic study of Balkan folklore. In spite of, or because of this litany of distinctive themes, Latch remains a cohesive work that could’ve only sprung from the mind of its director.

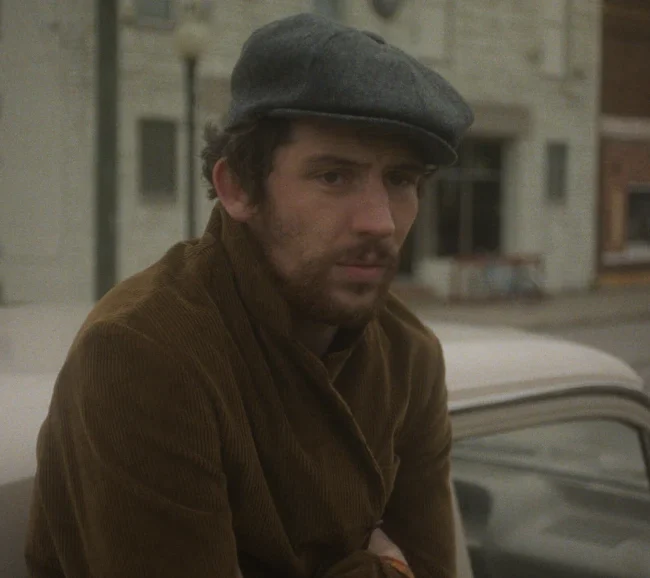

A kaleidoscopic prologue finds young New Yorker Sarah (Sarah Small) and her best friend Isolde (Isolde Chae-Lawrence) embarking on a trip to a forested Balkan cultural camp (a real establishment in Mendocino, California, appearing as itself) in an effort to outrun their own lack of self-control, which seems to continually land them in dangerous situations. The camp appears to offer courses in folklore and traditional music, but for Sarah and Isolde it seems more an excuse to drink, dance, gallivant through the trees and passively compete for the affections of Steph (Charlie Hewson), a young, banjo-slinging camper who resembles both an American Benedict Cumberbatch and an adorable, musically inclined woodland creature. While this would seem far more debaucherous and lively than you would assume a Balkan cultural camp would be, unfortunately for Sarah the murky atmosphere is more rife with unsettling peril than a simple Wet Hot Eastern European Summer, though the summer camp setting does well to visually expose the stunted, floundering nature of the two young women: all of the campers appear to be either much older, or young children.

Chilling moments, such as an expertly tense late night excursion that lands a drunk Sarah and Isolde lost in the woods, sporadically accumulate before culminating in hallucinatory daydreams and, finally, outright violence. All of this seems tied, albeit in typically mysterious fashion, to a folk hymn that Sarah sings to Isolde on their first night about a dragon that falls in love with a woman and becomes entangled in her hair, burning down the forest as he flies away with her.

Chilling moments, such as an expertly tense late night excursion that lands a drunk Sarah and Isolde lost in the woods, sporadically accumulate before culminating in hallucinatory daydreams and, finally, outright violence. All of this seems tied, albeit in typically mysterious fashion, to a folk hymn that Sarah sings to Isolde on their first night about a dragon that falls in love with a woman and becomes entangled in her hair, burning down the forest as he flies away with her.

The moody murk through which the story churns is abetted impressively by cinematographer Ashley Connor, who manages to inventively incorporate the flaws of the irascible Canon 5D into the film’s visual tapestry. The usually unseemly digital grain added by the camera’s lack of low light sensitivity adds a gloomy, degraded feel that heightens a scene lit only by a flashlight on the forest floor. Similar, she utilizes the finicky shallow depth of field to great effect by woozily keeping entire shots out of focus before suddenly racking sharply to minute details. Mike Frank’s sound design is equally exacting: incorporating wind rustle into a disorienting haze in the film’s darker moments before jolting the viewer back into consciousness with precise, eerie sounds—a door creak, the beat of a drum circle—that match Decker’s hyperactive, kinetic editing style jab for jab.

Too quick, violent, and messy to be mistaken for Kelly Reichardt and too ebulliently concocted to be mumblecore in spite of the improvised script, the internal loops of logic that keep audiences and critics hunting for similar movies or points of reference are totally irrelevant in this case: this is—incredibly, given that it’s her first narrative feature—a Josephine Decker film, through and through. The closest point of familiarity I could find was in the devilish, abstract montages that reminded me of Godard’s similarly dark and dreamy picaresque Weekend. Decker seems more interested in performance art than pre-existing cinema, anyway: her preoccupation is with using human bodies and physical forms to evoke insular feelings, from jealousy to loneliness to psychosexual longing.

This detachment from familiarity is both freeing and totally disorienting. At one point in the film, one of the teachers at the camp explains to Sarah that in Balkan folklore, even the most safe and familiar of images, such as doves and trees, can be possessed by dark and lethal spirits. Such wary advice pretty much sums up the tumultuous experience of watching Butter on the Latch. I was putty in Decker’s hands, without anything recognizable to latch onto. I don’t think I’ve ever felt less in control while watching a movie, which is an exhilarating experience in itself.

— Mark E. Lukenbill