BERNSTEIN’S WALL/THE CONDUCTOR

(The 2021 Tribeca Film Festival opened Wednesday, Jun 9, 2021 and ran all the way through Sunday, Jun 20. hammer to Nail has you covered with tons of coverage, coming your way! Like what you see here on Hammer to Nail? Why not pay just $1.00 per month via Patreon to help keep us going?)

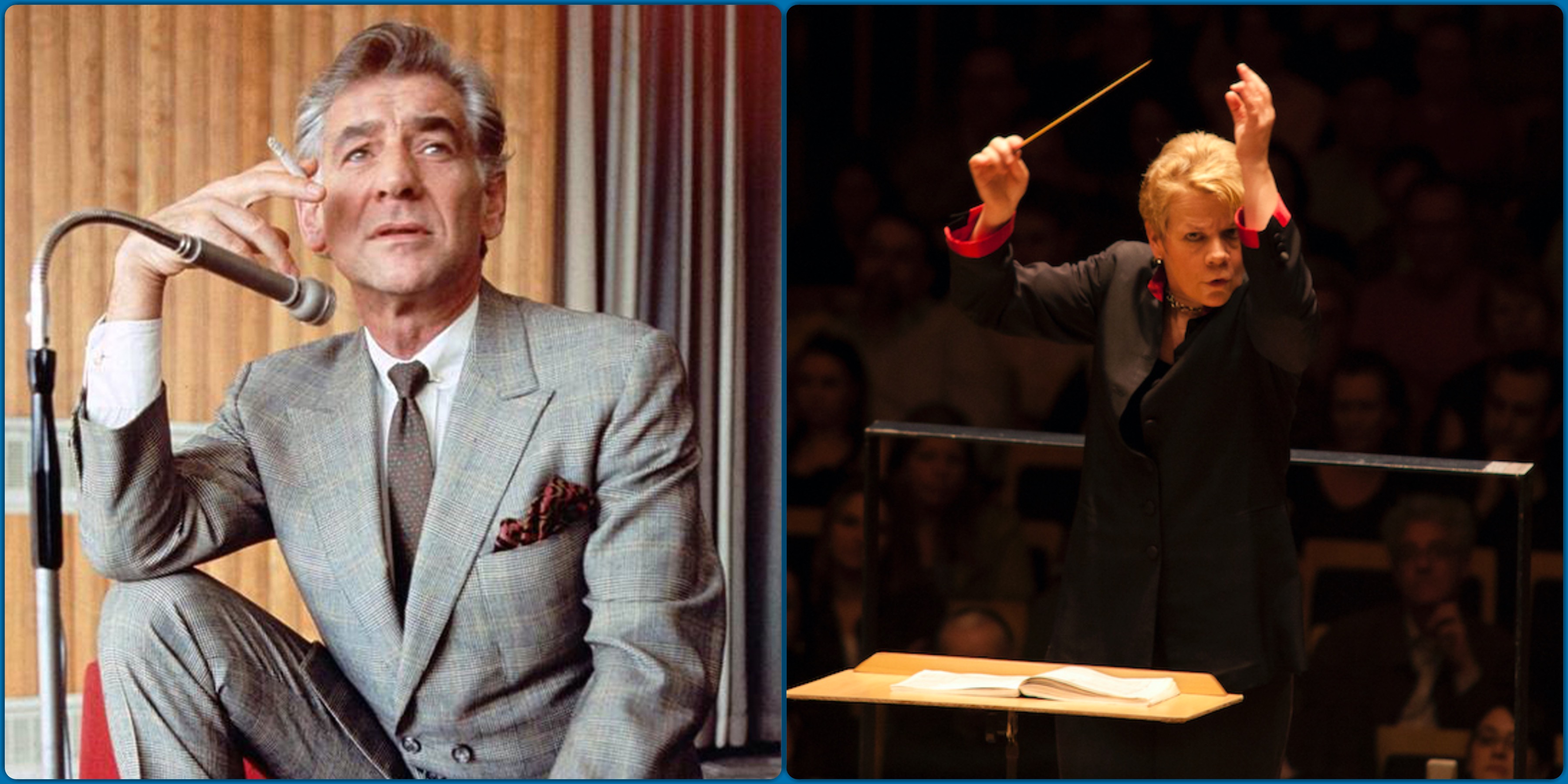

Born in 1918, Leonard Bernstein became many things, among them a musician, composer, educator and, perhaps most important of all, a conductor (from which most of the rest flowed). He matured at a momentous time in American history. Just as the nation was emerging from the doldrums of the Great Depression, the economic impetus of the World War II-generated industrial machine added to the New Deal’s successes to make the United States the powerhouse of mid-20th-century military, diplomatic and cultural might, for better or for worse. As a rising star of the classical-music universe, Bernstein therefore became an influential and inspirational figure to many, both here and abroad. As a Jewish man trying to break into leading one of the top symphony orchestras, he was considered ethnically unfit, until his rise to prominence opened doors for others to follow. In his new documentary Bernstein’s Wall, director Douglas Tirola (Drunk, Stoned, Brilliant, Dead: The Story of the National Lampoon) explores the life, career and legacy of his subject, who died in 1990, allowing him to speak directly to us via copious archival interviews. It’s a stirring, comprehensive portrait.

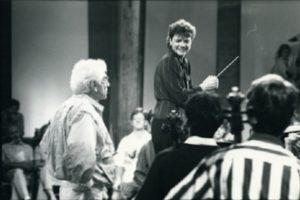

As is Bernadette Wegenstein’s The Conductor, which offers a similarly exhaustive (but hardly exhausting) profile of Marin Alsop. Both films have just played at the 2021 Tribeca Film Festival, and they are linked by more than their musical topics. As a young girl, Alsop attended one of Bernstein’s celebrated Young People’s Concerts, given with the New York Philharmonic, and it inspired her future choice of profession. Like him, she found barriers in her way, though for her they were far greater, since no woman had ever been appointed to lead a major American orchestra. Then, in the 1980s, Alsop studied with Bernstein, and still looks to him as a foundational mentor, even to this day. When, in 2007, she became Music Director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra (BSO), she was the first of her kind, breaking a glass ceiling that so far, sadly, no one else has broken. Through her own significant pedagogical efforts (another connection to Bernstein), however, she is likely ensuring that one day, other women may also reach that level. Wegenstein (The Good Breast) offers a lively, wholly engaging look at what makes this accomplished, electrifying titan of the music world tick.

Leonard Bernstein and Marin Alsop, Schleswig-Holstein, 1987

Bernstein’s Wall most likely takes its title (though this is never directly explained) from the 1989 Berlin performance of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” (from the Ninth Symphony), conducted by Bernstein in honor of the destruction of the wall dividing Germany’s once and future unified capital. He reworded the famous melody to read “Ode to Freedom,” instead, and given that he would pass away less than a year later, the footage of this event proves especially moving. By then, we have journeyed through the ups and downs of his then 71 years, including his big break at the age of 25 when a guest conductor at the New York Philharmonic, where he was assistant conductor, fell ill, giving him the chance to lead the orchestra for a live radio broadcast. An instant sensation, he never really looked back, going on to many accolades and opportunities. Most people today probably know him best as the composer of On the Town and West Side Story, though he wrote a far greater variety of music than that. And, as we learn from Alsop, his ability to make the classical-music scene appealing to mass audiences was unparalleled.

We also discover the challenges he faced as a gay man of his time. His sexuality did not prevent him, however, from marrying a woman named Felicia Montealegre, an actress, with whom he shared as much family time as his manic schedule would allow, and together they had three children, all of whom are still alive. We see, in superimposed images, the letters the spouses shared, including those that touch upon Bernstein’s homosexual desires (we see letters he wrote to others, as well). Theirs was a complicated, if loving, relationship, and Tirola presents plenty of home-movie and news material to document their life together (which ended when she died in 1978). Given Bernstein’s dedication to his art and teaching, it’s a wonder he had any time for anyone else at all. But beyond all else, one thing is abundantly clear here, which is that he had untold reserves of warmth, compassion and humanity which he tried his best to spread as widely as possible. Tirola, and his movie, do him justice.

Wegenstein is no less capable, and her protagonist no less worthy. Each movie allows its subject to narrate the story, Bernstein from beyond the grave and Alsop in her recent past and present. We join her in medias res, as she prepares to walk on stage at Baltimore’s Meyerhoff Symphony Hall (which, full disclosure, I have seen many times, just as I have seen Alsop, as I am a resident of that fair city). Conducting to herself, seemingly lost in thought, she nevertheless strides to her place, ready to go, focused, full of the charisma that has made her such a presence not only at the BSO, but in São Paulo, Brazil, where for 7 years she was also the music director of that city’s symphony orchestra. As we discover, despite her huge workload, Alsop has, in addition, found the time to manage the BSO’s OrchKids program for young people in the Baltimore area, as well as to teach classes at our Peabody Institute, with special emphasis on increasing access to classical (and all) music for traditionally excluded populations. Beyond her work training the next generation of female conductors, Alsop also empowers her students of color, as well as anyone who seeks her mentorship.

And, like Bernstein, she has a family, though unlike him, she has not had to hide her sexuality, and we meet her wife Kristin Jurkscheit and, from a distance, their son. Speaking of family, Wegenstein takes us back to Alsop’s childhood and early education, along with the negativity and pushback she encountered whenever she expressed a desire to conduct. Thanks to a mentor other than Bernstein, Japanese businessman Tomio Taki, Alsop, after being denied entry into Juilliard’s conducting program, was able to form the Concordia Orchestra and refine her craft there. Even then, once selected for the BSO in the mid-2000s, she had to weather criticism of her appointment, with the former conductor, Yuri Temirkanov, even publicly expressing doubts about a woman’s ability to manage an orchestra. Nevertheless, at all times she persevered and won the day, and now, in 2021, has finally stepped away from the BSO, though other gigs and opportunities continue to propel her into the future. Like Bernstein, she is deservedly one of the great celebrity conductors of her generation, her fame and recognition well deserved.

Together, then, these two movies make quite the pair, the one an inadvertent setup for the other. Directors Tirola and Wegenstein have each crafted rousing tributes to their main characters, filling the frame with a multitude of voices testifying to why we should celebrate both people. From Bernstein to Alsop and, we hope, long after, may outsiders prevail and lead others like them to the same (or even better) results. Let the superlative Bernstein’s Wall and The Conductor show you how it’s done.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)