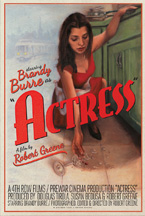

(Actress world premiered at the 2014 True/False Film Fest. Distributed by Cinema Guild, it opened theatrically on November 7th. Visit the film’s official website to learn more and find out about upcoming screenings.)

A character in a fictional film is created through the marriage of actor and director. Together, with two minds and one body, a third being is created, a person with fears and desires, weighed down by problems, buoyed by hope. In the realm of non-fiction—an increasingly precarious term in film as elsewhere—it is implied that the character and the person are one and the same, that there is no difference between the individual within and beyond the reaches of the frame. And yet, it is evident that the camera’s presence transforms that person into a character, that the subject becomes both hero and author of its own story. Robert Greene’s deft, meditative new film Actress questions the nature of performance—at its core, it’s a rumination on what performance means in a work of non-fiction—to seamlessly blend author and hero. And what better conduit to explore this through than an actor.

Brandy Burre, once an actor on The Wire, then a mother of two in Beacon, New York, now stands at a precipice. She finds herself with a life she cherishes yet all too often scarcely recognizes. Burre loves her children but feels stifled by the seeming finality of her imposed domesticity. Within the same scene, the same shot, Burre glows while looking down at her children, then looks off, confused at who just did that. Each look in the mirror, of which there are many, reveals a different self, a self searching for a different one. Part of her behavior, her need to perform, lies in the fact that there are secrets, ones that sustain her but come to bring everything crashing down.

Early on, Burre speeds into the city, relishing her newfound freedom (her kids are traveling with their dad). Greene stays at a distance as she saunters across a bridge with a light step. She’s with someone. She leans in close, but the other person is just off-screen. The camera slowly pans away taking in the skyline, and lingers there. Whoever that is, whatever is going on, is just beyond the reaches of this story. He’s in another movie.

Early on, Burre speeds into the city, relishing her newfound freedom (her kids are traveling with their dad). Greene stays at a distance as she saunters across a bridge with a light step. She’s with someone. She leans in close, but the other person is just off-screen. The camera slowly pans away taking in the skyline, and lingers there. Whoever that is, whatever is going on, is just beyond the reaches of this story. He’s in another movie.

Despite Greene’s efforts, this relationship finds its way into the narrative. Brandy’s partner Tim finds out about it (the “it” never explicitly stated) and leaves. “It’s an inevitable situation, but it’s not going to be easy, so (…) Everything… everything is tied in to one thing (…) Right now I’m standing in the fire and I need to step through the fire, not go back,” she confides to the camera. As the film wears on, and Brandy is worn down, it becomes increasingly apparent that she is performing for herself, the camera as mirror, trying to actualize a narrative she believes she is supposed to be in. She wants to choose her own story and uses the camera as a sounding board. She cannot figure out which one she is: mother, actress, homemaker, careerist. Most frustratingly—and justly so—she does not understand why she cannot be all at once.

But Greene, with his camera, is not simply a mirror. Actress has a levity, a grace, that lifts Burre above her problems, if only for a moment. In a particularly inspired sequence, Burre saunters through the house in slo-mo (an approach used again and again in the film, to great success), checks the chicken, moves past the TV and sees her daughter on the stairs holding a hanger. We don’t see Burre’s face but her body is open, thankful. Her daughter holds the hanger out to her, a meaningless gesture and yet it feels like the key to the city, the key to her heart. Burre lovingly accepts it and continues down the hall holding it up, a trophy, a testament to every decision that’s brought her to this point.

But Greene, with his camera, is not simply a mirror. Actress has a levity, a grace, that lifts Burre above her problems, if only for a moment. In a particularly inspired sequence, Burre saunters through the house in slo-mo (an approach used again and again in the film, to great success), checks the chicken, moves past the TV and sees her daughter on the stairs holding a hanger. We don’t see Burre’s face but her body is open, thankful. Her daughter holds the hanger out to her, a meaningless gesture and yet it feels like the key to the city, the key to her heart. Burre lovingly accepts it and continues down the hall holding it up, a trophy, a testament to every decision that’s brought her to this point.

Brandy is going to choose her own life, and she does. She tells her friends about her upcoming meeting in the city with her new love interest, but seems as though she is trying to convince herself as much as them of its significance. When dropping off her kids at Tim’s before going, she loiters, as if wanting Tim to wish her a bon voyage on her new life and love. It’s these seeming tone-deaf decisions that make Brandy so vulnerable, so relatable, so winning. Her life is messy; massive decisions are made with haste, ego and empathy constantly battle for control. In one breath, maybe a little drunk, Brandy brags about a new bathtub, legitimizes her fledgling career and makes a joke about her children drowning, all with the same cadence. She’s unsure what to say, so she says everything. She’s unsure what to do, so is left with no recourse other than to give it her best guess and run full speed in that direction. What else is there?

What makes Brandy, and Actress, so moving is that Greene lets us witness her transformation, the effort in each small step. Brandy’s myriad uncertainties, her roadblocks and dead ends, put her down but never break her. She is committed: to being a mom, to being an actress, to being an honest person. “I guess I’m clumsy, perhaps not very graceful,” she says at the end, explaining an accidental fall that left her face cut and bruised. It’s perhaps the only lie told in the movie; Brandy is not clumsy, she is graceful, and she knows it. Sometimes you fall flat on your face. With Greene’s help, Brandy Burre shows the truth, the beauty, in admitting defeat, looking at yourself in the mirror, and then moving on.

— Jesse Klein