A Conversation with Visar Morina (SHAME AND MONEY)

Visar Morina was born in Pristina, Kosovo in 1979, when the region was still part of Yugoslavia. At 15, his family fled as refugees during the turmoil that would eventually lead to the Kosovo War, and he has lived in Germany ever since. Between 2000 and 2004, he worked on various film and theater projects, including as an assistant director at the Volksbühne Berlin. He then studied directing and screenwriting at the Academy of Media Arts Cologne, where his graduation film premiered at the Max Ophüls Festival and was broadcast on ARTE. His 2013 short Von Hunden und Tapeten screened in the international competition at Locarno and was nominated for the German Short Film Award.

Morina made his feature debut in 2015 with Babai (“Father”), a father-son story set in pre-war Kosovo that drew heavily from his own experiences. The film won Best Director at the Karlovy Vary Film Festival, multiple prizes at Munich, and was selected as Kosovo’s entry for the Academy Awards—only the country’s second-ever submission. His sophomore feature, Exile (2020), starred Mišel Matičević and Sandra Hüller as a couple grappling with identity, integration, and workplace alienation. The film premiered at Sundance before screening at the Berlinale, and its screenplay won the German Film Academy Award. Exile was also selected as Kosovo’s Oscar submission.

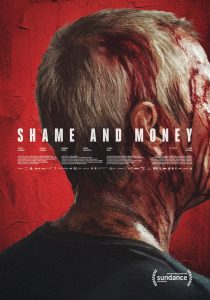

His third feature, Shame and Money (which Chris Reed reviewed here), marks his second premiere in the World Cinema Dramatic Competition at Sundance. Co-written with Doruntina Basha, the film stars Astrit Kabashi as Shaban and Flonja Kodheli as Hatixhe, a Kosovar couple forced to leave their rural farm and move to Pristina after their livelihood collapses. As they take odd jobs to survive—she as a caregiver, he as a day laborer—they find themselves navigating a transactional world at odds with their values and dignity. The film took home the World Cinema Dramatic Grand Jury Prize at the 2026 Sundance Film Festival. I spoke with Morina about several key sequences in this interview, which has been edited for length and clarity.

SPOILERS BELOW

Hammer to Nail: At the 12-minute mark, we get this dinner sequence where Liridon and Labino get into a fight. It is all done in one take behind Mother. Liridon explains that he only needs 1,800. Labinot tells Mother that he is trying to get together with Agron who brought a knife to school. Apparently Liridon wants to team up with this supposed gangster to “Take care of old people in Germany.” Liridon responds, “at least I ask, At least I don’t hide the money from the family.” Labinot taunts him saying, “do you know how much I make, of course you do, you have stolen it many times.” Liridon threatens to punch Labinot. Labinot slaps him three times and he stands up from the table. Mother forces him to apologize. This is such a great introductory sequence, can you talk about what was important to you?

Visar Morina: This was the very first scene I wrote. I was working on something completely different, and it is funny because it has stayed exactly as I wrote it the first time. What was important for me there was actually what they are dealing with. Kosovo is such a small country, and they are so accustomed to not having a state—or let me put it differently, not having the chance to call the police if you need help, because over many years, the state was the enemy. So it was very important how your reputation is. For example, if your neighbors like you, they will help you in case you need help. This reputation thing is very important. I do not think it is just in Kosovo.

I like very much the fact that they are both accusing each other of the same thing. The older brother is telling him, “You have stolen,” and the younger brother is telling him, “You are stealing.” I was very much looking forward to shooting it. I was very lucky. There is no other scene that I rehearsed longer. We were rehearsing for three days before we shot. But it was also a great introduction for the actors to the film. Then I did something on set. I asked the younger brother to hit back once, and he did. I knew the next take would be the best, and it was. That take is in the film. I really wanted this tension and this feeling that at any moment it could explode.

HTN: The performances there are so great, and I love the framing of that scene. At the 24-minute mark, we get this scene where Shaban is mucking out the cow shed. Hatixhe comes in and says, “What are you doing, for God’s sake?” Shaban proposes they plant some peppers. She responds that it is only 80 cents a kilo. “How many kilos do you want to plant?” He goes back to mucking out the shed. We cut to him sitting in the shed alone and then we cut to black.

This song, which I believe is repeated throughout the film, plays over a black screen and we find ourselves in the city where the rest of the story will be told. Why was this the last scene you wanted to show in their hometown? And can you talk about the intended effect of the cuts to black that separate time for us in many instances throughout the film?

VM: The song actually happened when I was with my girlfriend in my flat. We were listening to Albanian music and this song appeared, and I thought it might be great for this part. I connect the song very much with my mom. I think my mom would too. I wrote the script, especially the first part, for the house I grew up in. I grew up with my brothers. The field he is referring to and the village he is referring to, it was all real.

The whole idea was basically a very simple question. I once did a photo of the main characters, Astrit and Flonja, and somehow I got reminded of my parents. My parents left Kosovo 30 years ago, and I just asked myself how it would be if they would leave today. Since I wanted to make it very fast and very intimate, I thought it was best if I wrote it for the house where I grew up. I did not end up shooting there, but it felt very natural for me to find a dead end. Being in the barn, I very much liked it. Also the fact that he keeps working. I just finished my film now, and I do not know what to do tomorrow. When you get used to things, you just keep doing them. It felt very natural.

HTN: I really love that scene, and I also loved returning to it on my second time watching the film. At the 53-minute mark, we have this confrontation between Shaban and the landlord. He wants to get back his mother’s lira, which was used as a deposit and has sentimental value for the family. The landlord mixed up that the lira was for the deposit and the money was for the rent. Shaban asks for it and the landlord explains that he sold it. Shaban asks him to take him to the place that he sold it and the landlord says, “It’s done, man,” and asks him to leave.

Shaban gets in the way and says he will not leave without the lira. The landlord says, “You seem like a good guy. Don’t screw it up now.” The landlord opens the door and Shaban, in frustration, grabs him and gets punched in the face. The scene ends in a long shot of him on the floor as the landlord looks over him. This is the first outburst we see from Shaban. Can you just talk about crafting this moment and what was important to you?

VM: Your questions are interesting because I also become aware of how many things just happened by accident. This lira thing, for example, my mom has a lira for each of us. In my case, she lost it, and then she bought a new one. After she bought a new one and gave it to me, she told me about the stress she had and how bad she felt not having a lira for me. The lira is some kind of security. It was a security in old times, but even now—gold is very expensive. The more insecure people feel, the more they go back to gold. Since Kosovo went through a long period of very insecure times, the gold and lira were important things. Over time, they also gained sentimental value.

The scene for me has also a tiny bit of humor in a weird way, because he ends up in a very bad position. But what was very important for me was thinking of Shaban as a person who gets political awareness throughout the film—being aware of where you are standing and how people are looking at you. On the script level, it was very important to me because he is basically trying throughout the film to know where to put a fence for himself. Where he is being used and where not. This scene was one of his first attempts to make boundaries.

HTN: At the hour and five-minute mark, Lina gives Hatixhe a jacket and says, “I knew it would be nice on you.” Hatixhe looks reluctant in accepting the jacket as she says, “I feel a bit strange. I don’t know how to say it, but it feels like you’re buying me. My sister, I’m happy to help you. You don’t owe me anything.” The scene ends with the sister explaining that she asked her husband if she could give this to her, and he said yes. This is a smaller moment in the film, but one that really stuck with me. Can you talk about your thinking?

VM: I do not know if you have seen a film called Ali: Fear Eats the Soul. I watched it many years ago, and there was one strange tiny scene. Ali comes home and tells Emmi he worked today and had put money into the kitchen shelf. Emmi says, “But why are you doing this?” And he says, “But I am living here.” And she says, “I am enjoying you being here.” The scene stayed with me because within a few seconds, the question of prostitution came in. What am I benefiting from you and what are you benefiting from me? That scene had a very big impact on me. I do not think without that scene I would have come up with this scene here.

For me, there is no scene on a script level that clarifies more the heart of the film, at least how I saw it. There is this boundary, this line between empathy and profit. The scene ends with her having to go to the doctor and asking Hatixhe to make dinner for her in-laws. I felt the scene was trying to explore this very thin line: when am I being used? When do I become a servant? When am I just a human? When am I just an idiot or an asshole?

HTN: I really love that moment. I think it has such great subtle acting in it. At the hour and 26-minute mark, we have this sequence where after being told off again by Alban, we find ourselves back with Shaban as he is cutting down a bush. He plucks at the leaves from the bush in a normal way until his employer comes in behind him and says, “How much do you normally make?” Shaban responds 20 and the employer leaves him 30 euros, saying, “You seem like a good guy.” This obviously calls back to the exchange with the landlord, and Shaban responds, “What does this ‘good guy’ mean?” The man does not respond as Shaban begins to chop into the bush recklessly. The man grabs him and they struggle. He rips away the garden tool and pins his face to the ground and says, “Are you out of your mind?” Shaban, out of breath, simply says, “I’m sorry.” Can you talk about crafting this moment?

VM: I like this line very much, “You’re a good guy.” It is much used in Kosovo. A friend of mine who is a theater director reminded me of Woyzeck, this play by Büchner, where the same term is also used—”a good guy” or “a nice guy.” Sometimes as a child, I felt it is also used as a ticket to fuck someone over. “You are a good guy”—meaning there is no danger coming out of you.

Astrit Kabashi and Flonja Kodheli appear in Shame and Money by Visar Morina, an official selection of the 2026 Sundance Film Festival. Courtesy of Sundance Institute | photo by Janis Mazuch.

Also, the translation is not perfect. I realized yesterday in the dinner scene, the brothers also refer to him as “the good guy.” “He’s the good guy. That’s why you’re doing this.” If you think about this political awareness thing and being aware of classes—”Oh, you are the good guy. That’s why I can do this.” I like the effect of him reacting but at the same time feeling very sorry and feeling very stupid that he has done it. I think he really means it when he says, “I’m sorry.” He said it like three times. Then he stands up and starts cutting again.

HTN: At the hour and 40-minute mark, we probably get my favorite sequence in the film—this incredible moment with the Clinton statue. It starts in the sky and we find Shaban sitting in line waiting for work. Someone offers him water repeatedly. He is completely despondent but finally responds, “No, thank you.” The camera drifts across the line, slowly making its way and hovers over the ground. As the theme of the film grows more intense, the camera from a distance spots this statue and makes its way over to it.

We find the statue framed behind an American flag as well as the blue sky until we find ourselves enveloped by this wedding party. Then the music cuts out as we find ourselves in silence—we see the people celebrate this joyous occasion. Was this a moment that was originally in the script? Can you just discuss crafting it generally?

VM: This was written in the script and very important for me. You have to know that Kosovo went through an awful time with Milosevic. The war in Bosnia and Croatia started, and the situation in Kosovo—actually, all the Yugoslavian wars started basically in Kosovo. People were there waiting for the war to come. It was a really awful, very harsh time. Then the war came, and when NATO interfered, for many people it was a huge thing. If you see images of the first NATO soldiers entering the country, people were going crazy, bringing flowers. That is why there is a huge admiration for Clinton, because he was the president at the time, and also for the US.

The biggest street in Pristina, when you enter the city, is named Bill Clinton. There is the statue. Funny enough, this street where the workers stand and wait every day to find a job is next to it. When we did research and saw the streets, there was Bill Clinton. While writing, I just ended up being there, and I thought it would be a very long sequence. It is. It was also really fun to shoot. The funny thing was people took it for real—you see a hundred-dollar bill on the head of the musician. This comes from a man approaching, thinking it was real, going to the musician, putting the money, and leaving.

HTN: That moment really feels so alive, and that is why I was wondering if it was originally in the script—it just feels so spontaneous and amazing. At the hour and 52-minute mark, Shaban is back at the same employer’s house where he got into the fight. He is hammering away at something when the man asks him if he wants any food. Shaban, as always, says “No thank you” and goes back to his work.

After a minute of working further, something snaps and he stands up with the hammer, enters the house, and framed entirely outside of the door, we slightly see and hear the commotion go down. The glass of the door breaks. Shaban jams open the door and, covered in blood, he begins to walk and walk and walk, framed right behind his neck as we often see him throughout the film. Was this shot towards the end of filming? Can you talk about your decision to not show the violence, only the aftermath?

VM: I like, on a conceptual level, the idea of violence when it comes to describing things. I experience many things in our everyday life as very violent. But it is very hard for me to find a way to get the idea of violence into the film without making it graphic, without making it concrete. Then it gets only shocking, and I feel it misses the point.

While preparing this film, just before I was about to write the script, I ended up by accident reading a book about violence—about different forms of violence, also violence we do not see. For example, that time was Corona and we had the lockdown, but the people who delivered the food did not have it. In Germany, people who do jobs like this get terrible pay for it. Very often there is one company hiring another company so that they are free of any legal responsibility. This thing works only if I am threatening them with, “I will get you out of the system if you do not do what I tell you.” This is also a form of violence. If I believe in physics, and I do believe, I need some reaction to push this. Thinking in these terms, how much violence we actually experience every day, I feel that humankind is way more peaceful than you would think.

I think people take shit to a certain extent. At some point, it does not work anymore. It is always a question of the character. I feel we are heading in a direction that scares me. When you compare, for example, how the middle class in Germany is disappearing—how people who had a normal job, how much they could afford 30 years ago and how much they can afford now—it is crazy. I think this has an end to it, also in terms of violence.

I liked not showing it. Violence easily becomes pornographic. I really wanted to avoid that. I liked very much the fact of him walking through the street covered in blood and everyday life continuing around him. I feel very often people walk through life—they are not covered in blood, but they eat shit alone. Very often silently. And very often unseen by many people.

– Jack Schenker (@YUNGOCUPOTIS)