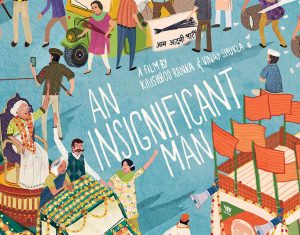

A Conversation with Vinay Shukla (AN INSIGNIFICANT MAN)

I met with documentary filmmaker Vinay Shukla, on Saturday, June 17, 2017, at AFI DOCS 2017, to discuss his feature debut, An Insignificant Man (which I also reviewed), co-directed by Khushboo Ranka (she did not attend the festival). The movie tells the story of Arvind Kejriwal, a populist politician in New Delhi, India, who rose to prominence, along with the party he founded, the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), in 2013. It’s a fascinating look at the intersection of passion and ideology, truth and power. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, which I recorded immediately after watching the film (I usually have more time – days, sometimes – to devise questions).

Hammer to Nail: Your film opens with a title card telling us that you made this film thanks to 782 crowdfunders. Who are these people?

Hammer to Nail: Your film opens with a title card telling us that you made this film thanks to 782 crowdfunders. Who are these people?

Vinay Shukla: They are people from all over the world, who are looking for alternative narratives in politics. They are young people, mostly, who want more voices in the media. As you know, this is a political film, following the journey of Arvind Kejriwal and the Aam Aadmi Party, who are activists who decided to come into politics and are today key figures in the Indian political arena. So, we were following them and trying to make a film. We ran out of money. We asked a lot of people for money, and they said, “You know, it’s a political film in India. Indian people won’t touch it.” So we finally went in for a crowdfunding campaign. We were very hesitant in setting our target, so we set a limit of $20,000.

HtN: Which crowdfunding site did you use?

VS: We set up our own website. So we basically said that we were looking to raise $20,000. We cut our own trailer, and we ended up raising $120,000.

HtN: Wow!

VS: And that should give you an idea of just how much people are seeking an alternative dialogue around politics in India right now.

HtN: But these funders weren’t all from India, you said…

VS: Yeah. From all over the world.

HtN: So let’s back up for a second. You said you were already filming when you ran out of money, with your co-director Khushboo Ranka. This is your first feature. Had she made a feature before?

VS: No, this is the first feature for both of us.

HtN: How did you two meet?

VS: We met on a previous film, called Ship of Theseus, on which she was the co-writer and in which I, for my sins, had acted. So, that’s where we met, and then this film happened as a collaboration.

HtN: Got it. So, what initially drew you to this subject?

VS: So, our subjects were very popular anti-corruption activists in India, and then they decided to form a political party, and it was a very divisive decision. People either thought it was a great idea or a pathetic idea, for activists to get into politics. And somewhere, both us – me and Khushboo – were also arguing about it, whether it was a good or bad decision. And we realized that there may be a story here. The conflict between the two of us made us realize that maybe more people want to know whether this will be a good or bad idea. And so we just moved to Delhi, with our cameras, and we started filming them and the project evolved from there.

HtN: And where are you from, originally?

VS: Bombay.

HtN: So since I have never been India, let me ask you about the languages in the film. There are at least two – Hindi and English – and there’s a fluidity between the two, as people go back and forth between one and the other. Are there any other languages that I’m not hearing?

VS: No, that’s mostly it, because Delhi is a predominantly Hindi-speaking region, and the language of Delhi politics definitely fluctuates between Hindi and English. There are more languages spoken within Delhi, but those are languages largely for personal use, within families, etc.

HtN: It reminds a little bit about how I’ve heard language used when watching documentaries set in the Philippines, where people go back and forth between English and Tagalog.

VS: Absolutely. Because language is about expression, and you employ all the tools that you have at hand. In India, there is also something – at least within my family and Khusboo’s – we gesticulate much more, in our hands and our faces, in expressing what we need to tell.

HtN: Well, I’m half-French, and the French gesticulate quite a lot, as well. And my mother has always gone back and forth between French and English in the same sentence, so I understand.

VS: (laughs) Exactly.

HtN: So, is that letter that Kejriwal reads, from Sheila Diksit [his political rival, and then the Chief Minister of Delhi], real? It almost feels like a political stunt. Was that an actual letter?

VS: Yeah, yeah! Absolutely! It’s a letter that they presented in court as evidence.

HtN: OK, so that was a genuine moment. I’m cynical, these days, after own 2016 election.

VS: As you should be. As every citizen-journalist should be.

HtN: Well, that was a really interesting moment. What does “Aam Aadmi” stand for?

VS: Common man.

HtN: So it’s the Common Man Party.

VS: Yeah.

HtN: What is the new party that the guy who is kicked out of Aam Aadmi, at the end, is now starting?

VS: Yogendra [Yadav] has started something called the Swaraj Abhiyan, which is the Swaraj Party, and their policies are about more decentralization of power. They believe that Aam Aadmi Party is not decentralizing power enough.

HtN: So, one of the things that is extremely impressive in your film is your level of access. Your camera is basically there, all the time. How did you get the trust of your main protagonist and of everyone else involved?

VS: So, when we started filming, there was really nobody interested in these guys. People thought that these activists forming a political party was career suicide. So, when we went in there and said we wanted to film them, they were more than happy that somebody showed up with a camera. And it started from there. After that, for the next year and a half, we would just turn up and make sure that we were as unnoticeable as the furniture. And, you know, as my co-director Khushboo says, at one point people started putting their bags next to us, because we did actually become the furniture, because they realized that we were going to be standing there all day. And as somebody in journalism will tell you, it’s also a daily struggle. On some days, you get great access; on some days, you don’t. And then you try, on the edit table, to stitch together your best moments and create the narrative that you want to.

HtN: I love how you say “edit table,” as if you’re cutting on film. Did you start, in your own career as a filmmaker, cutting actual film?

VS: No. I am a child of the digital age. The only reason I am able to make films is because cinema has gone digital. If it were still on film, I probably wouldn’t have access to the resources – the cameras, the edit machines – that I do.

HtN: Hear, hear! And yet, you still say “edit table.” (laughs) So, you shot over a number of years … how big was your crew? Was it just you and Khushboo, with one on camera and the other on sound?

VS: We started with just the two of us, and then we were joined by our associate director and cinematographer Vinay Rohira. So, inherently, in the beginning, it was just the three of us, doing as much as possible. We didn’t even have a sound mic – no audio equipment – just a camera with a mic on top of it, because we thought that was good enough. And then the political party started getting much bigger than we could have anticipated, and Khushboo realized that we needed to expand. So she went around to colleges, hiring people – young students – and training them on cameras. And then we bought sound equipment and trained these young students on sound equipment. So, by the time we got to the elections, we had 4 units – one person on camera, one on sound – and all of them were either self-trained or trained by us.

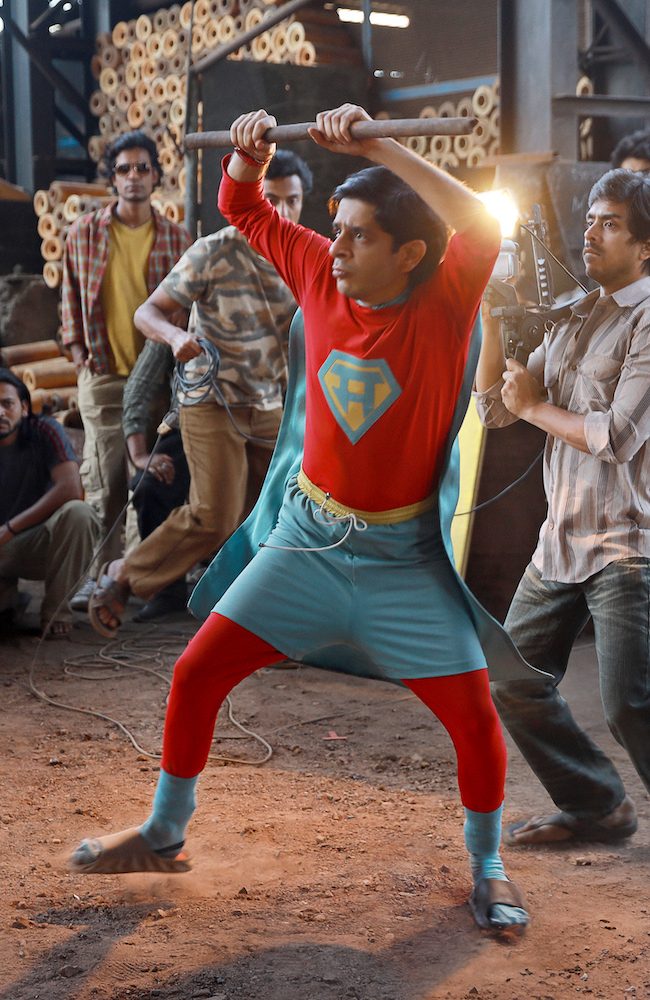

HtN: Interesting! And now a question about Indian cinema, which is incredibly vibrant, with all kinds of movies, from the great art cinema of people like Satyajit Ray to Bollywood cinema. I haven’t seen a lot of documentaries out of India, however. Is that a vibrant movement in India, as it is here?

VS: It’s becoming more vibrant right now. And that’s partly because of the access to digital cameras and resources. It’s becoming more accessible for people to tell their own stories. However, it’s important to remember that in India, documentaries are still not a viable career choice, and for good reason. There is not too much of a documentary-funding infrastructure; there’s not too much of a documentary-exhibition structure. We are a country that is still grappling with a lot of basic problems, and making documentaries is perceived as a certain luxury by most people.

Also, documentaries are seen as coming out of a kind of activism: unless you’re looking to change something, as an activist, you shouldn’t be making a documentary. Which is not entirely true. People also want to make very personal stories about, you know, relationships, which can be told through the medium of documentaries. But it would be very difficult for that person to get any sort of funding, even internationally, because personal stories attract much less funding than ones about societal change. And that should give you an idea about the economics of documentaries, even in America.

And so imagine applying that to India. If someone wants to make a personal film about, you know, their grandparents or their own struggle with alcoholism … unless you have a strong activist cause, it’s very difficult to get funding for documentaries. So there are challenges that Indian filmmakers face, but over the last two or three years, there has been a rising documentary current. More young filmmakers are coming out and taking greater risks than I have seen earlier, in terms of embedding themselves in really, really dangerous situations; embedding themselves in all sorts of set-ups; and coming out with new stories. So I think it is an exciting time.

HtN: Excellent! Well, thank you very much, Vinay, and congratulations on the film.

VS: Thank you so much.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)