A Conversation with David Shadrack Smith & Jake Fogelnest (PUBLIC ACCESS)

Director David Shadrack Smith just premiered his feature-documentary debut, Public Access, at the 2026 Sundance Film Festival (where I reviewed it). The film showcases all the wild, vibrant, and very weird content that proliferated on New York City’s Manhattan Cable channel in the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s. Thanks to a state law that required big media companies to fund the public’s right to use at least a small chunk of the airwaves, Manhattan Cable offered everything one could not see on mainstream television, including porn. I spoke with Smith, as well as with Jake Fogelnest—who appears in the film as his teenage self, hosting Squirt TV—during the festival via Zoom. What follows is that conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: I know you have some information about this in the film, but can either of you explain, as you understand it, the New York state law in the 1970s that required broadcast companies to maintain public-access cable channels?

David Shadrack Smith: I’m going to turn this one over to Jake Fogelnest, who is not just the original influencer kid, who had his own TV show on public access at 14, but also sort of an unofficial historian of New York.

Jake Fogelnest: It’s really interesting. They wanted to create this thing, cable television, which would give you better reception and more channels, channels like HBO and basic cable. And in order to do that, they had to dig up the street and run wires underneath the street. And some media activists and people said, “Now hold on a second. If you’re going to mess up our neighborhoods and do all this construction, if you’re going to lay this cable, you need to allocate a certain number of channels to be used by the public for whatever the public wants to do.” And it being cable, it was not mandated by the FCC. So they agreed. They said, “Yeah, we’ll do that.” And when they did it, they thought, “OK, people will talk about their school-board meetings and they will talk about community affairs.” But they found themselves very quickly surprised at what they were legally required to put on television.

DSS: Which was anything and everything. And it really was this sudden space that opened up. The great glitch in the media universe opened up this space for the public—first come, first served—with no editorial control. And it was very quickly found by New York’s wildest people.

HtN: As your film makes amply clear, because you have some amazing archival from that time. Your film also makes clear at the end that the rise of the internet basically wiped out the demand for public-access cable. But do any such channels still exist in New York or elsewhere that you know of? And is anybody watching them?

DSS: Absolutely. They’re still, to me, a vital alternative to mainstream media. They exist all around the country. Look for yours in your locality. They’ve changed a little. They function a little bit more like networks now. I think there’s more editorial control and a certain sense that maybe not everything can be on cable access the way it was back then.

JF: Basically, the cable companies at a certain point said, “We’re going to turn this over to a nonprofit and they’re going to be the arbiters of what goes on the air.” And I know of people with public-access shows in Manhattan today where they’re not allowed in the offices because they’ve threatened people with physical violence, but they still broadcast their tapes on TV.

DSS: The mission is still carried on. BRIC, in Brooklyn, where I live, is a great network. Our story ends when the internet starts because I think it was kind of a handoff and an idea that all new technologies and revolutions are going to be replaced one day by the next technology and that we start this cycle over and over again of what are we going to do with this space, this technology, this opportunity? How come it keeps defaulting to the crazy and wild and what are we okay with? And the story of Public Access is an encapsulated metaphor for what is happening in social media and the internet at large, and who knows what the next one will be?

HtN: So, yours is not the first documentary I’ve seen where you don’t show your interview subjects and just use audio. But why did you decide to do that, to just have the voices speaking rather than cutting to talking heads?

DSS: It’s a great question. We actually started filming some of our subjects when we were developing the film and early interviews. I have to give credit to one of our executive producers, Benny Safdie, who saw an earlier trailer cut and said, “Don’t include that; you don’t need it. We don’t need to see the people. We want to stay immersed in the world. We want to live in the archive, make the experience as much as possible like you were there at the time watching public access, stumbling on these shows. Live it as an experience.” And I think we were nervous about the fact that some of the archive is old, it’s grainy, it’s glitchy, and maybe the talking heads would give us a break from that. But I think, in the end, that idea of immersion in this world, in this time, really worked. And I can’t take credit for it.

JF: One of my favorite things about the movie is that David doesn’t use as much of the interviews, so that some people who have never seen the archive can really see it. And the way that David just artfully uses the interview audio as a storytelling device, it’s awesome. And in the process, you also saved so many tapes that would otherwise have disintegrated into dust, which have been digitized and archived.

HtN: How did David approach you, Jake, to be in the film? What was his pitch?

JF: He sent me an email.

DSS: By the way, this was also because of Benny Safdie, who was a fan of your show. Benny said, “You’ve got to talk to Jake Fogelnest.”

JF: Yeah, Benny and Ronnie Bronstein.

DSS: And Josh. Josh Safdie.

David Shadrack Smith and Jake Folgenest attend the premiere of Public Access by David Shadrack Smith, an official selection of the 2026 Sundance Film Festival. © 2026 Sundance Institute | photo by Gabriel Mayberry.

JF: So these guys knew my show, and I think we have a mutual friend in the great Tom Scharpling. But I was thinking about this time of public access concurrently with David. David reached out and I said, “Oh, so have you talked to this person? Do you have this footage?” And everything that David was saying about the way that he wanted to make this movie was spot on and right. I’ve always felt that this story needed to be told. And over the years, lots of people have reached out to me about my footage or doing a documentary about myself, and that could happen at some point. But really I said, “I’m a small part of this much larger story.”

And David just really had the whole story and he had the big picture of it. And it was very, very easy to say, “OK, here is the footage.” And then David said, “Do you have anything else?” And I found things that I didn’t even know I had, footage that my mother had shot on a video camera of me as a very little kid. I was like, “All right, David, I will give it to you for the greater good of telling this story.” This was a couple years ago now, but it was just sort of an instantaneous, great collaboration with David and his entire crew.

DSS: And we’re so grateful to all the producers who not only made their shows but saved their tapes and trusted me with the archive.

HtN: And your inclusion, Jake, was an interesting element because it shows how we have this alternative form of media, but then you go mainstream from that, and then it goes even more mainstream. And David draws a direct line between Wayne’s World and you.

JF: Wayne’s World was a sketch on SNL and a movie, and the great joke of the movie is that they rebuild Wayne’s basement in a studio. So what happened with me is I’m doing this public-access show out of my bedroom, and I’m very aware of Wayne’s World. And I say to MTV, “We have to still shoot this out of my bedroom. Otherwise, it’s the joke from Wayne’s World. It’s going to look like a corporation came in and co-opted it. ” And amazingly, MTV said, “Yes, we can shoot it in your bedroom.” Now to anyone, I say, “Don’t film in your apartment if you can avoid it. It’s a huge pain in the ass.” But I was able to keep the authenticity and stuff while using all the resources of the MTV machine, which was about an extra, I don’t know, $500 or $600 because it was MTV in the ‘90s. But basically, Wayne’s World happened to me in real life.

DSS: It’s really hard to quantify the impact of public-access television, but when you see shows like Wayne’s World, it’s New York in the ‘80s and ‘90s, SNL, David Letterman, MTV itself … the aesthetics of public access were really seeping out into the world.

JF: I started to notice it in commercials where people were doing a shaky cam or a fisheye lens. And I was like, “Oh, this is from public access and this is from skate videos.” It’s that ‘90s underground culture which became the mainstream for better and for worse.

HtN: It sounds like you approached people and you got footage, with Benny Safdie helping you. Were there any areas of difficulty in terms of obtaining access either to people or to footage?

DSS: Sure. Yes, absolutely. Not everyone wanted to relive that time. Some people wanted to make documentaries of their own and wanted to hold their footage back. For many of the creators, this was a big moment of their lives and they have been sitting with it for a long time and would like to tell their own story.

JF: Which is probably why they did a public-access show in the first place.

DSS: And those films will come out, too. In our story, our main character is the medium itself; every story in there could be its own film. And I hope one day you’ll see the Jake Fogelnest story or the full Al Goldstein story.

JF: Yeah, Al has had documentaries that he did, but it was important to me that I not be the main character in this story because I had to grapple with the fact that I am a character in this larger story. And that’s what I really connected with David about, that he wanted to make a film that was representative of the whole medium. How did this happen? How did it get to where it was? And he very artfully shows us and doesn’t tell us, “Oh, here are the parallels of how it exists in our world today.”

DSS: A lot of other footage, especially from the early days, is gone. And that would be hard when we’d hear about a story and you couldn’t find it. It just didn’t exist anymore. But then there were these wonderful surprises that you would find along the way. Somebody said, “I remember when somebody filmed a live birth and put it on public-access TV and we have to find that story.” And it led us to Bob Gruen, who was this legendary rock-and-roll photographer in New York hanging out with John Lennon, watching public-access TV from the Dakota.

JF: Filming the New York Dolls. He is a complete legend in rock. And I had no idea until I watched the film for the first time that, “Oh yeah, he had his wife’s birth. He just put it on TV.” Incredible.

DSS: And he had the tapes and it’s just like, “All right, that’s great. That’s what we’re here for.”

HtN: It’s pretty incredible, especially if you know the history of early broadcast television, with the challenges that Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball faced in just having her be pregnant on TV, and then to think that this guy filmed his wife giving birth. It sort of blows your mind. It really does.

DSS: And that was very early on, within a year or so of public access launching. 1973 or something.

HtN: It’s pretty incredible. So, have any of the Supreme Court issues discussed in the film that allowed Manhattan Cable to continue to broadcast sex and nudity affected what is happening today on the internet or in broadcast? How do you see changes in law, or free speech, still being allowed, and how are we being limited, or not, today?

DSS: The story we tell in Public Access is one that keeps enlarging as it goes along. So it starts out with this kind of local version where New York City and Time Warner, which own the cable lines, are battling it out and whenever they try to control the creators or censor something, they have a little lawsuit or maybe they work it out in the back room. And then it goes up further and further and as cable grows, you get the first Cable Act by the FCC that mandates that these channels should exist around the country. Those challenges come in a new form later on with, I won’t go into all the complexities, but they try to do an opt-in, opt-out version that sort of leads to the Cable Act of 1992 that protects the space, and then they further refine that with the Cable Act of 1996.

And what is precedential about these for the world we live in now is they became what we call the carriage laws. So they sort of delineated the line between, “OK, you’re the provider, you’re the utility, and these are the content makers, and your utility is not necessarily responsible for the content.” And that was a line that was drawn in public access that protected both sides in a funny way.

JF: A major precedent for so many things in the world today.

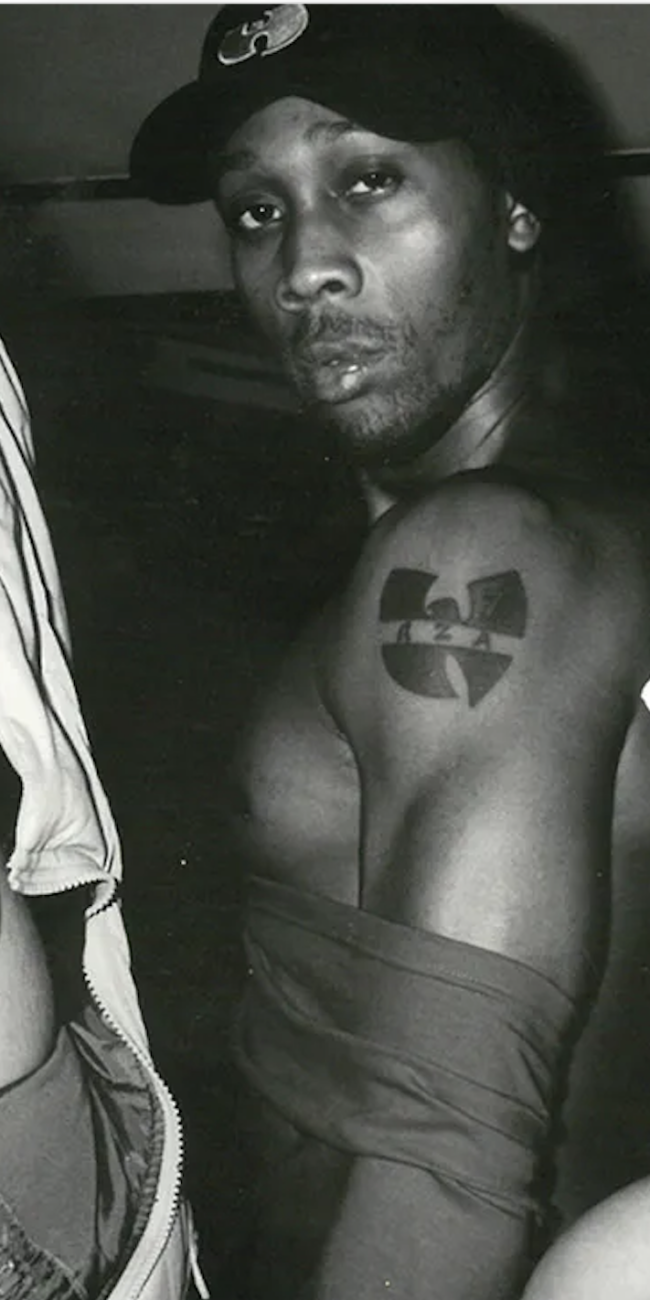

A still from Public Access by David Shadrack Smith, an official selection of the 2026 Sundance Film Festival. Courtesy of Sundance Institute | photo by David Shadrack Smith.

DSS: And where are we today? I wonder what would happen, and we will see because it’s happening, when these kinds of free-speech First Amendment cases reach today’s Supreme Court. Will they still believe and enshrine the opportunities that are created by the First Amendment? It doesn’t feel like we’re entirely in that environment. And we’re now seeing states all across the country trying again this sort of opt-in, opt-out version where you have to provide an ID to access certain sites. I get it, protecting children, all the reasons are there, community standards, but the line becomes super fuzzy and you’ve now got your driver’s license attached to Pornhub, for example.

JF: Is that good?

DSS: We’re really right back in those stories and the courts in those days were willing to take a very First Amendment-forward position. I don’t know that that’s where we are today.

HtN: Well, I think your film definitely raises a lot of important issues and will hopefully get people to think about all of this in a new way. So, gentlemen, I want to thank you so much for chatting with me.

DSS/JF: Thank you!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)