A Conversation with Olivier Assayas (SUSPENDED TIME)

French writer/director Olivier Assayas (Clouds of Sils Maria) returns to the big screen with his latest feature, Suspended Time, a deeply personal meditation on life, love, art, and memory. The narrative is set during the initial COVID-19 lockdown, with Assayas’ characters—two brothers and their girlfriends—stuck at home. In fact, that rural space is the actual property of the director, where he and his real-life brother spent their childhoods. As such, the movie explores reflections and echoes within the world of an artist and his work, often blending the line between fact and fiction. Vincent Macaigne, Micha Lescot, Nora Hamzawi, and Nine d’Urso star as the isolated foursome. I just reviewed the film for Hammer to Nail, and I also had a chance to recently speak with Assayas via Zoom. What follows is a transcript of that conversation, edited for length and clarity. Assayas speaks excellent English; any occasional changes made to match American idioms are my own.

Hammer to Nail: How would you describe the relationship of cinema to time? How do they interact?

Olivier Assayas: I think that art is about time, in general, at least the art I relate to. And I’m saying that in the sense that things are transient and art somehow freezes them in time. But you can also put it in a different way, saying that it captures the effects of time. I think time is what transforms us, and it’s what transforms the world around us. And I’ve always been fascinated by the capacity that filmmaking has in capturing it and somehow unveiling the complexities of it. It’s exactly what the Georges Brassens song at the end of Suspended Time says. It’s this beautiful poem by François Villon, which is about how things fade in time.

HtN: So how then does Suspended Time fit into these ideas of cinematic use of time?

OA: Well, it’s a movie that I always hoped that one day I would have the opportunity to make, but I was not sure it was going to happen, although I’ve been doing movies that are autobiographical. Many of the movies I’ve made are autobiographical. But also, I was aware that you can’t be completely autobiographical in movies. I mean, you can play with some sort of autobiography, but ultimately it becomes something else, with actors, different places. What I wanted to experiment with—and I genuinely think that the world “experiment” applies to this film—is what if it were the real places? What if it were the real words? What if I set it in a moment in time, which everyone is aware of and everybody has an experience of, so it can echo with the experience of other people.

It involved exposing myself, it involved being realistic, being truthful in ways. As much as I’ve tried, I haven’t really completely succeeded, but no one really completely succeeds. But at least I tried one more step in the direction of autobiography. And I was touching at things that were extremely intimate, like having a portrait of my grandfather, whom I never knew. He died in 1936, and I never knew my grandmother, either. They were Hungarian, but they were there watching, they were looking at me; the paintings were there on the wall, and there was a portrait of my mother as a little girl painted by her father, my grandfather.

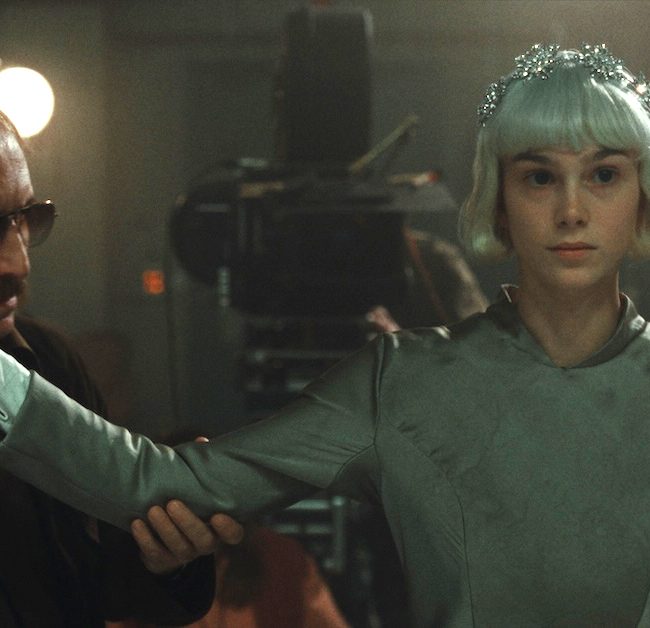

Olivier Assayas, on set

It’s the easy way, of course, to say that they’re ghosts, but it’s not exactly ghosts. It’s more like how time moves and how time stands still at the same time, because I could make a perfect case of explaining why time is at a standstill in this film, but I can also say that it’s also very much in the present tense. And it’s one of the beauties of cinema to be able to look at time at a standstill, freezing time.

HtN: Did you always expect that you would speak your own voiceover in this film rather than, let’s say, having the actor Vincent Macaigne do it?

OA: It’s just the way I wrote it when I was writing it. I said, “OK, it’ll be my voice if it works. I don’t know if it will work.” But ultimately I knew that there had to be a narrator, and the narrator could be myself. And I was surprised how easy it was. I mean, when we recorded the voice, we did it in two takes and it was done. And to me, the inspiration was Guy Debord, the French philosopher who made a movie called In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni [Latin for “We Go Round and Round in the Night, and Are Consumed by Fire”], which is a palindrome, and it’s a semi-autobiographical movie, and he uses his own voice. And I’ve always been a great admirer of Debord. And I suppose that when I started writing, even if it was not that crystal clear in my mind, I was inspired by Debord to use my own voiceover.

HtN: I think it adds a really interesting element to the film, and I’m glad you did that. So, you talked about ghosts, but I also find it fascinating in your film how you returned time and again to this notion of duality—doppelgangers—and mirrored lives. I was looking over my review of your 2018 film Doubles Vies [“Double Lives”], which in English was called Non-Fiction, and I was reminded of how often you use this idea of duality. And here in Suspended Time, we have you narrating and Macaigne playing you. You have the two brothers, the two girlfriends … What draws you, do you think, to this notion of rippling echoes throughout the universe, doubling doppelgängers? You return to this quite frequently in your work.

OA: I think you’re perfectly right. It just happens to me. I suppose that it’s the way I write, but in Suspended Time, it’s very different because it’s a case of reality outdoing fiction, because I represented what I lived. So, this is not a dramatic creation. This is a reconstruction of facts that happened to real-life characters, and that’s the way it went: I was there with my girlfriend, and my brother was there with his girlfriend, and it was not going to be some kind of comedy, some kind of adultery comedy like Non-Fiction.

It’s about a double duality, in a certain sense, because it’s two couples that we see blooming. We see two couples at the very beginning, and it’s still fragile. I mean, love is there, but it could be gone. And so, you have these two middle-aged men who both are in a situation of having a new relationship with slightly younger women. So, I think that there is duality in the sense that it’s two couples, but there’s duality also within the evolution of the couples. But then I didn’t want in this film to have anything dramatic or artificial or exaggerated. So, I wanted to have something very subdued, very quiet in terms of narrative.

Assayas on set with Vincent Macaigne,

I mean, there’s hardly any narrative. It’s just four people, one set. We shot it in four weeks. I just wanted to capture the stillness of time. But I was also constantly aware of what was going on underneath the stillness because I think it was a time of fear and anxieties, but you had to repress them in a way, because what was going on was extremely scary. And my brother reacted with anger. He hated it. He hated the fact that he was locked down, that anybody dared to question his freedom of movement. I was anxious, I was scared, and I was not angry. I was happy we were in a lockdown. I thought it was the only way to deal with the pandemic. But as quiet as the movie is, it still echoes the pain, the anxiety, the anger that was.

HtN: So, you wanted something very gentle. There’s sort of a minimalist plot. It’s very like Éric Rohmer in that sense. But you have made all different kinds of films, from action thrillers like Carlos and Demonlover to more dramatic material. You’ve really tackled quite a lot of different genres. What’s pushed you towards one genre or the other as you’ve gone along? Or does the story just push you in one direction vs. another?

OA: To me, it’s always about exploring something that I have not done. When I finish a film, whatever it is, I feel that I can’t go one step further in that direction, so I have to reinvent myself. And I think that in art, it’s extremely important to be able to have the capacity to reinvent yourself because otherwise you repeat yourself, which is the worst crime. And also, I get that question once in a while because obviously that’s the way I function and it’s different from other filmmakers.

The thing is that you have a lot of filmmakers who recreate the world in a specific environment, Aki Kaurismäki in Finland, Ken Loach in England, and others. They make movies, but they recreate the whole complexity of the human experience within a specific space. I think that I do things the other way around. I mean, there is at the center something that is the complexity and the diversity of reality. And sometimes I film it from this angle, and sometimes I film it from that angle. And ultimately, with every movie, I try to use an angle that I haven’t used before, which forces me to reinvent myself, which forces me not to rely on my old tricks.

But I think it’s the accumulation of the movies I’ve been making. I mean, they communicate with each other. I genuinely think that it’s the diversity of the movies I’m making that is ultimately what drives me. What makes me want to move on and keep on making movies is the fact that there are movies that I have not made yet in an environment that I’m hardly aware of.

HtN: Well, that seems like a wonderful philosophy of life, as well. I want to thank you very much for speaking to me.

OA: Thank you so much. It was a pleasure.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)