A Conversation with John Sayles (LONE STAR)

John Sayles is one of the great American filmmakers. Graduating from Williams college in 1972, Sayles moved to east Boston to work a factory job. During that time he wrote short stories, submitting them to various magazines. These short stories would be compiled into a full novel in 1975 called Pride of the Bimbos. In the late 1970s, following in the footsteps of many great filmmakers, Sayles worked for Roger Corman as a screenwriter. Saving up money he made from that job, in 1980, Sayles grabbed his friends and in 25 days made the monumental Return of the Secaucus Seven. Many attribute this film as the kickoff of the American independent movement of the 1980s. For the next 20 years, Sayles would rise to the top ranks of American filmmakers. He not only served as writer, director and editor on The Brother From Another Planet, The Secret of Roan Inish, Passion Fish, and, City of Hope, he also was an actor in Malcolm X, Something Wild, and, Matinee. This status was fully solidified by his 1996 masterpiece Lone Star. The film has been recently restored by Criterion and the sentiments ring just as true today as they did in the 90s. It was an honor to speak with John Sayles about the film in the following conversation edited for length and clarity.

Hammer To Nail: Mr. Sayles, Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. I am a huge fan of your films and so is my dad. Also, as someone who studied urban studies at the University of Pennsylvania you may be surprised to find out your films and novels are heavily involved in the curriculum. My introduction to you was City of Hope, however, I will not waste anymore time, I would love to talk about this terrific film. The criterion edition of Lone Star looks amazing. Talk about the restoration process. What went into it? And why now?

John Sayles: First off, Criterion told me that they would like to restore the movie. They had already done a very good job with Matewan. The nice thing is to be able to go back and not only restore the film from what it once was, you can actually utilize digital techniques to make things even better! I sat with Stuart Dryburgh the cinematographer and approved the whole process.

For example, the first scene, it was 95 degrees out in this desert, however, it was overcast, so we never quite got it to look as hot as we wanted it to. This time around we were able to bring up the color and mess around with the saturation to make it look like a hotter sequence! There are little tweaks like that you can do to make things even better. The other great thing about restoring digitally is, that is how it will always be. As great as film is, the prints can degenerate. The chemicals begin to do their work and can go pink or fade a little bit. It can get scratched up if its been played in a projector many times. It was great to be able to sit down and repair certain shots as well as make them better with newfound technology.

HTN: Well, the film looks great. You began your career as a storyteller writing short stories and eventually a novel, you also throughout your career dabbled in production, editing, acting. How has being a part of many different aspects of the storytelling process impacted you as a filmmaker?

JS: People have asked me if writing novels and short stories influenced my career as a filmmaker, however, being an actor influenced me majorly. I acted a little in college, and had done some roles in other people’s films as well as my own. As an actor, what you do when you play a character is you take the text, what you see in the script, but then you have to think about where this person comes from. Are they rich? Are they poor? Are they educated? Do they have certain prejudices? What do they know? You have to ask all of these questions.

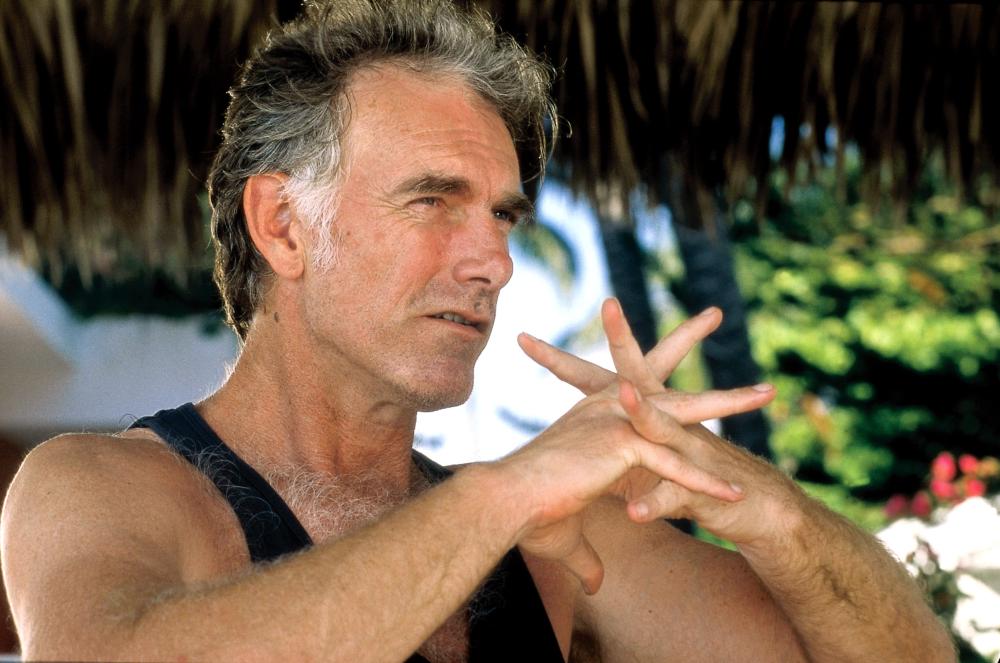

Filmmaker John Sayles

When you are writing a character, you do the same thing. Having been an actor has been very useful to my fictional writing as well as my screenwriting. When I write a screenplay, or characters in fiction, I read them out loud as if I had to play them. Not that I would cast myself to play these roles, but, it is valuable to think about it as an actor to see if there is enough there. Is my voice and diction consistent?

Having been a novelist I was spoiled because when you write a novel you write the first, second, third and final draft. When it came to movie making I wanted that kind of control. For me, serving as an editor is just the last draft of the story. I have worked with very good editors a couple times but, finally, I felt like it is just so much fun for me to edit and I am going to be in the room anyway so I might as well just sit at the machine and do the editing myself. I edit while I write because I have to consider the budget. I am also editing when I am shooting. Mentally I am saying to myself things like “Ok, I got enough from this angle to be happy in the editing room.” Actors will tell me that they blew a line every take and as long as it is a different line then I have got what I need. For me it is all part of the storytelling. I would never hand over one of my novels to someone and say, “Ok, you see what I have done here, finish it for me.” I ask their opinion of it like I ask audience members but, I would never ask them to actually sit down and move things around.

HTN: I think you can feel that total control, especially in a film like this one, Lone Star, and your films in general, are always entrenched in the location they take place in. In Lone Star, this Texas Border town serves as the main character, what led you to this location, this story and what research tactics did you deploy to so accurately depict it.

JS: I had hitch hiked along the Texas border a couple of times. The main thing I realized is that there is this border separating Mexico and America, yet, everyone on the American side speaks Spanish at home. That is their first language. They have cousins on the other side and every day they cross over to the other side and vice versa. The fluidity I knew something about.

As a kid, I was fascinated by the story of the Alamo. It is one of the basic Texas legends but it is also an American legend of these freedom fighters. I got to come down to Texas to do a little part in this movie Piranha I had written. I had a day off and I took a bus to San Antonio to actually see the Alamo. The day I was there, there was a protest march on the Alamo with Chicano people saying, “why don’t you tell the whole story?” I knew some of the story, but decided to do a little more research and realized it was a much more complex and interesting story than the one in the legend.

One of the major things was that there were Mexicans inside of the Alamo like Santa Ana, and they never get mentioned. The other thing is that one of the main freedoms the Texans were fighting for was the freedom to own slaves. Mexico had outlawed slavery. Their friends in Louisiana were getting rich growing cotton and they thought they could do that in Texas. That is a major complication in the legend and it is not part of the story that we were told. So I thought that this was a great place to talk about how the legend part of history can be destructive. We tell legends because it is how we define who we are based on where we are from. Well, what if when you look at it, it is not something to be that proud of or it is just so complex that it is not nearly what happened. Culture and history are a battlefield and it was back then when I made the movie. Still today, states like Texas and Florida tell their schools they cannot teach parts of history in certain ways. Whether it is the truth or not, teachers must teach certain things or they can lose their jobs.

HTN: The film is still timely that is for sure. I think one of the most fascinating elements of this masterful script is how every character seems to cross paths at some point except Chris Cooper and Joe Morton’s character. Why did you decide to do that?

Chris Cooper in LONE STAR

JS: There are these communities in the southwest that have always had an army base. Fort San Houston and San Antonio these places are where the buffalo soldiers were stationed. There were black soldiers who were so badly treated by white Texans. The Brownsville incident was why there were no combat soldiers in America for years until after World War 2. They got so sick of it that they went to Brownsville, Texas and started shooting at Klans people. Teddy Roosevelt, who was the president at the time, deemed it too dangerous to have black people in the army in possession of weapons. That is a pretty heavy thing for the legacy of our country. People who wanted to serve their country, fight in wars and maybe get killed couldn’t because of their race? They had proven time and time again that they were perfectly good soldiers. I wanted to deal with that. These places have their official history and then there’s the real history. This has created divisions in these towns where people stick to their kind. Mexicans, whites, the army people, they all think they have nothing to do with each other. In actuality in the past you did and in the present you do, whether you want to admit it or not.

HTN: A moment I find fascinating is between Sam Deeds (Cooper) and Hollis (Clifton James) on the fishing dock. Hollis says to Sam “look at all of this will ya! Tackle, boat, all just to catch a little old fish minding his own business down at the bottom of the lake. Hardly seems worth the effort, does it?” I think this is a fantastic line and in retrospect knowing how it ends is even more fascinating, talk about your thinking behind this line?

JS: This is something that is part of film noir. The detective comes in and the chief of police says you’re off the case. It’s Chinatown, you know? Do not go there! We make decisions like that all the time. District attorneys absolutely know someone is guilty but what will it cost me politically or what will it cost in terms of money? They consider these things and think we may not have enough of a case because they are so powerful or so many people do not want to believe that that is true so they just do not get into it. They tell their assistant DAs not to spend any more time on that. It is a cold case that is going to remain cold. That is basically what Hollis is saying. He’s saying that Deeds is only going to make trouble poking his head around this case. You are also not going to be happy with what you find. He’s suggesting we put our hands over our eyes and forget about it. It is the way that very often we choose to live.

HTN: At around the hour and 20 minute mark we get this gut wrenching sequence in which Enrique (Richard Coca) is murdered. Talk about the way you depicted the violence in this scene and what you hoped to accomplish by stripping the moment of any music or flashy camera angles.

JS: What I wanted there was a lack of subtlety. He literally winks at the deputy when he shoots the guy. It is a situation of Kris Kristofferson’s character realizing that Enrique is not playing by his rules. He has to make an example every once in a while. The word is going to get out that he did it and he wants it in that community. He also thinks that is genuinely what he has been elected for. To hold the line against these people!

There is this long history between the Texas Rangers, who historically are depicted in a historic light and the Mexicans. It was a guerilla war. Some of it was racial and some of it was them realizing that they had land they wanted so they decided to make life very difficult for the Mexicans in the area. If you go to a lot of, mostly African-American, neighborhoods, there is a guerilla war going on between the people who live there and the local police force. There have been worse times, Like Chicago in 1968 when they killed Freddie Hampton. There was then this killing war and cops were getting killed just because people hated cops. If someone was wearing the uniform they were the enemy. There had been that on the Texas Border for years and years and there is still a little residue from it. Charlie Wade, at the time that this film takes place feels like he is just doing what his people have always done. That is how you hold the line in their book. Every once in a while you have to waste someone so they take you seriously! Jail time means nothing to these people, but if you kill someone they will sit up and pay attention. That is his mentality.

HTN: The violence is handled in a very matter of fact way. As you’re talking, it is clear that the film feels more inspired by real life situations than it does any specific film, however, I am wondering, since you are working in a Western genre in a sense, did you watch any of those films to prepare to shoot this film?

JS: It’s funny, Matewan is honestly more of a western even though people wear cowboy hats and boots in Lone Star. Whenever you shoot anywhere near a genre you have to understand that people are coming into the film with certain history and expectations. The movie Unforgiven works because it is Clint Eastwood. He is a guy who can barely sit on his horse or shoot straight for 80% of the movie. At the end, when he kicks ass, and blows away everyone at the bar, the audience accepts it because he is Clint Eastwood and we have that history with him. He knows that as a director and that’s why he cast himself. While he is getting the shit kicked out of him by Gene Hackman, the audience is thinking, oh god do not do that. Don’t you know that is Clint Eastwood? You know what is going to happen. You have to be aware of those things to the point where when you go against expectations you must have laid some groundwork for that.

Then people will begin to realize it is a different kind of western. There is some nuance and some complexity here. There is a sheriff who doesn’t even want to be a sheriff. He is bound to ask some questions, and go through situations that are not standard for the genre. He is opening a cold case that he has got some personal involvement in. You would think he would want to cover it up, actually he wants it to be his father who did the murder. He wants his father to end up being the bad guy. As he goes along he learns that it is even more complicated than he previously thought. The first movie I thought of was the punchline of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. I also thought of One Eyed Jacks because it is a father/son situation. The personal, political and racial all in the same story. I was also aware of the Oedipus story. The searcher who finds the answer to the murder and realizes it is not what they hoped it would be. Sam can deal with the truth, he wont gauge his eyes out, but he is certainly turning that badge in.

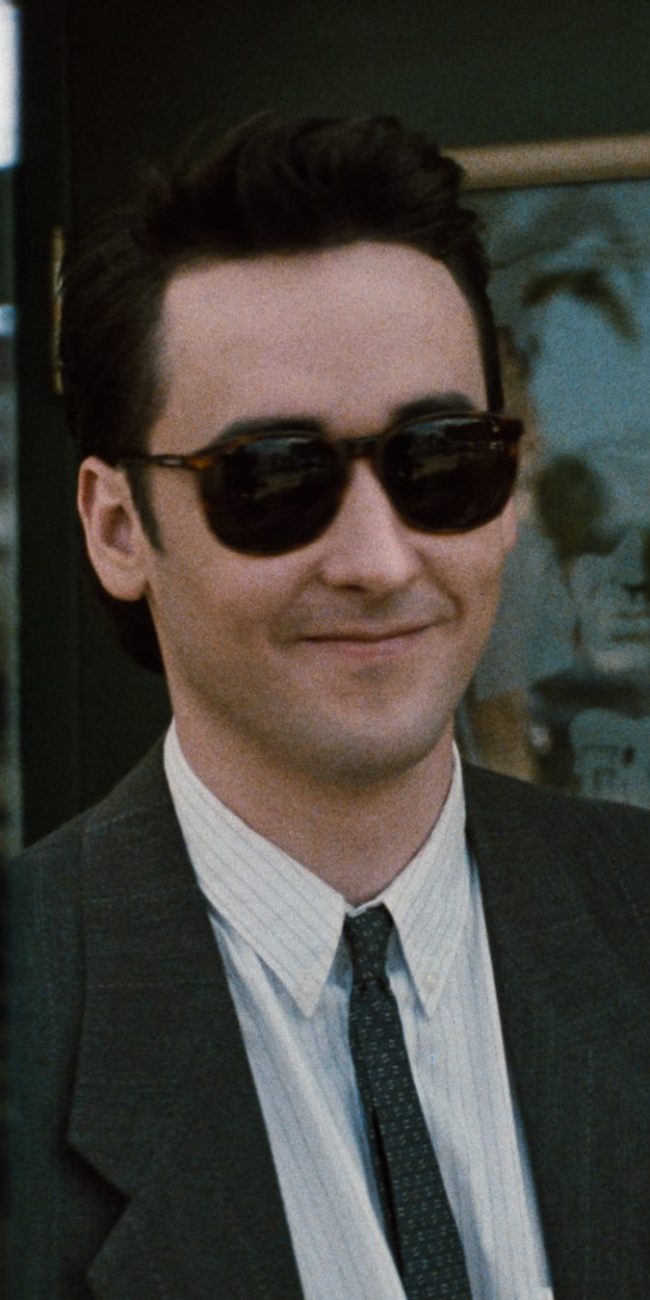

Matthew McConaughey in LONE STAR

HTN: I only have time for one more question so I must ask you about this line. in a conversation between Montoya (Tony Amendola) and Sam. Montoya says to him “step across this line. You’re not the sheriff of nothing anymore, just some Tejano with a lot of questions I don’t have to answer. A bird flying south, you think he sees this line? Rattlesnake? Javelina? Whatever you got. You think halfway across that line they start thinking different? Why should a man?” Absolutely brilliant line: what made you think of it?

JS: Having crossed borders where they are not monitored and then going to the sections that are monitored it’s a strange feeling. Animals obviously do not recognize these lines. Animals can create their own territories, for example dogs when they pee, these are not natural constructs much like the borders are human constructs. I did some publicity in Berlin when it was a walled city. Two hours into a foreign country and you get to this city with a wall and barbed wire all around it. All of a sudden you are in West Germany. That human construct of cement and barbed wire is a physical wall but it is also symbolic. In this case it is symbolic of the Cold War.

Our wall is getting bigger and bigger because the symbolism is important, not because these Texas border towns want to be separated. They were fine when you paid a dime and you went through a turnstile. There was a bar with great margaritas that our crew went to every day and they would have to pass that turnstile. The people on the other side were fine when you paid a dime and went to the other side for a Walmart because it was cheaper shopping for certain things!

The Anglo dentists had their practices on the other side because they did not have to pay the insurance for malpractice that is on the US side so they could charge less! Nobody would go to a dentist on the Anglo side because you are paying the insurance companies. The people in these towns do not need that line. It is people elsewhere who do. Some of it is for a real reason, everybody cannot just come here, the border cannot be that poor but, it is also symbolic of a proxy war of your either with America or you are a traitor. So they put up a wall so they would not come, but, guess what, they are still coming. I was just at the wall. It is billions of dollars of metal sunk into the ground and going up. People are still somehow getting through. We are still pouring money into it because of how important that symbolism is to certain people politically.

So with this line, I really wanted that idea of what are the things that we as human beings allow to separate us. Is it age? Is it sex? Is it religion? Is it ethnicity? Is it Nationality? When do we do that? When do we ignore it? When a war happens, for example, all of the sudden, Japanese Americans, we do not trust them. Sometimes, politicians think, we want everyone to be white in this area or everyone who can vote in this area must be white so let’s change the laws. The black laws in Virginia for example. Every 3-4 years there would be a new black law restricting what free people of color could do! When you see these laws you realize that a person was behind all of it. One of the first black laws is, if you have an illegitimate child with one of your enslaved people, you cannot leave the land to them or you cannot give them your name. That is against the law because people were doing that! People on a human level said, “I am not going to let that line separate me from my son or daughter anymore.” In order to stop these people they had to put up a symbolic law to keep them separated. This is a question that we live with as a society and as a world constantly. What are we going to allow to separate us?

HTN: It was really such an honor to sit down with you today Mr. Sayles, I think Lone Star is such a masterpiece because it is so specific to its town but also serves as a microcosm for America generally and yeah, they are not making them like that anymore. I am going to tell all of my friends to check it out.

JS: Thank you so much!

– Jack Schenker (@YUNGOCUPOTIS)

Mike Mejia

Thanks for posting this, great interview! I will make one minor correction as someone who has seen Lone Star probably more than anyone: the person Charlie Wade kills onscreen is Eladio, not Enrique. Enrique is the present day restaurant worker who tries to do the same thing as Eladio, smuggle people from Mexico to the United States. However, Enrique is not killed in the film. Very astute observation that Joe Morton’s and Chris Cooper’s characters never have a scene together, and I believe it is because they have parallel journeys to come to grip with their fathers’ pasts.