A Conversation with Jafar Panahi (IT WAS JUST AN ACCIDENT)

Dissident Iranian director Jafar Panahi (3 Faces) just won the Palme d’Or at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival with his latest movie, It Was Just an Accident, which asks viewers to consider what they would do if offered a chance at retribution for harms done to them. When mechanic Vashid hears the telltale dragging step (from a prosthetic leg) of a man walking into his garage, he immediately recognizes him as his past torturer. Convinced he is right, he pursues his ostensible enemy into town, knocks him out, and prepares to bury him alive. But then he starts to have doubts and so seeks out other former political prisoners for confirmation. What then follows is a taut quasi-comedy of errors, where the very real stakes of authoritarianism mix with the absurdity of fate. I spoke in person with Panahi at the recent Middleburg Film Festival (where I also reviewed the film), and here is that conversation, edited for length and clarity. Since Panahi does not speak English, the interview was made possible with the assistance of interpreter Sheida Dayani, who translated from English to Farsi and back again.

Hammer to Nail: Your characters are often driving in cars in your films. What makes you want to make this a part of your stories?

Jafar Panahi: It’s not that all my films happen in cars, but rather that vehicles factor in because of the kind of work we do, the kinds of films we make. Because I was banned from making films, I had to work where I would not attract attention. Either I had to take refuge at home or somehow hide my camera if I went outside.

One of my films that happens entirely in the car is Taxi. I did not have permission to shoot or work but was trying to shoot on the streets. As soon as you bring your camera on the street, they’re going to come and arrest you. So filming this way has a security function, but this doesn’t mean that I don’t also try to work it into the story in a way that makes sense for the story.

If the film is about a taxi driver, there is no other way to show that world other than showing him driving a taxi. And, in this film, the subject is about a body that is being transported around a city, and there is no other way to do that than in a car. So I had to take refuge in the car. So I don’t understand this question of why there are cars in my films. There have to be cars.

HtN: This is true, but I have to note, nonetheless, that in your films, characters are frequently driving to a specific destination, except, of course, in the movie where you are in your apartment.

JP: Yes, they’re going places.

HtN: Despite the seriousness of your subject, your film has a lot of comedy; it’s a comedy of errors, in many ways. How did you manage this tone in your writing?

JP: There are elements in the film that are really not considered funny in my culture; they just seem very commonplace. But in another culture, they cause laughter. For instance, this same film causes laughter in one way in North America but in East Asia—Korea, for example—it causes laughter in a different way.

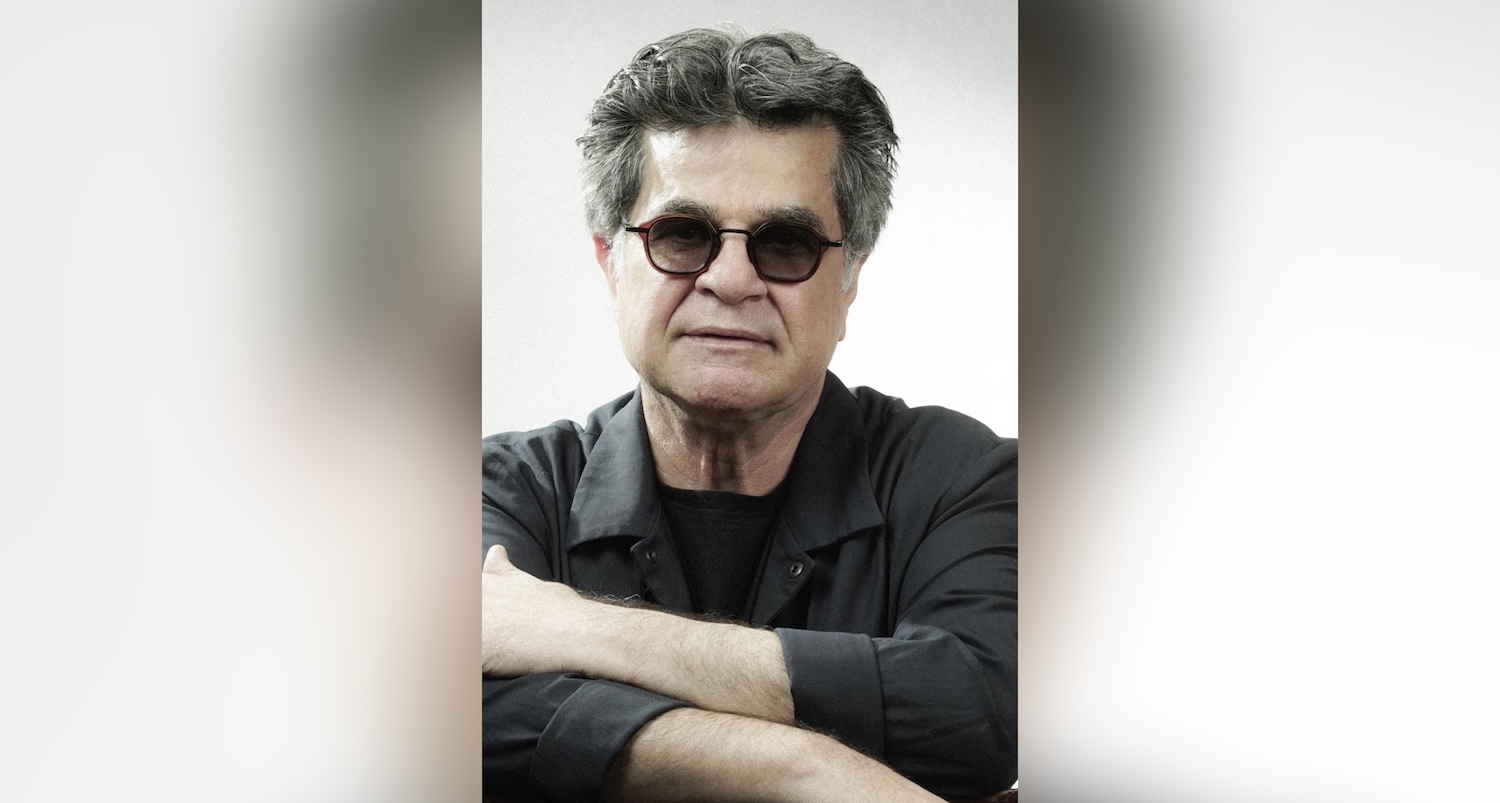

Filmmaker Jafar Panahi and our Chris Reed

Having said that, I did want the audience to have some kind of a bitter smile up until the last 20 minutes of the film. And then, in the last 20 minutes, I wanted to do something to the audience that would shock them. If I didn’t bring humor to the first part, the film would be monotonous and the audience, at the end, would not be shocked. Since the audience becomes accustomed to seeing every shot with its own comedy, when there is no humor at the end and they keep seeing that nothing is funny and everything’s getting more and more serious, they turn inward and their senses become heightened. When they leave the film, it is impossible for them not to be thinking about it.

HtN: It must be fascinating for you to travel with the film and see these different reactions. I didn’t think about that.

JP: Before I had all these problems with the ban on my films and being banned from traveling, I used to travel around with my films and see them with an audience.

HtN: I am very interested in the technical history of the movie and how you started editing in secret using proxy files and then completed post-production in France. Could you explain how that worked?

JP: The White Balloon was my first film, and nobody takes you seriously with your first film. I took the five reels of negative to the lab where I was going to do the sound design. The sound designer and I watched it together and then he told me that if I wanted to change anything in the film I had to do it before he started working on the sound, because if you change it after he started working, we’d have a problem. He said, “After I add sound, you can’t touch it.” I didn’t say anything; I just took all the negatives and left.

He asked me where I was going, and I said to him, “Until my film is released, if I feel that there is anything extra, I‘m going to cut it.” The editing process continues all the way until the film comes out. It’s only when you add sound to the film that you finally realize some things about it, such as if this shot needs to be longer or shorter. Or perhaps sound can help bring two shots together.

I didn’t go to France specifically to do the editing and post-production. The first sequence is such that I could not shoot it in the streets, because if I did shoot in the streets I would have to bring a large process trailer for Eghbal’s car, and with all that, everyone would see it and we would be exposed. So I did it instead with a green screen and then in France I added the background. I then continued with post-production sound and editing once I was there.

HtN: I really enjoyed the cast. I know you have your nephew, Majid, who was also in Taxi, as well as Vahid Mobasseri, who was in No Bears. How did you cast the other actors? I particularly like the actress playing Shiva the photographer, Mariam Afshari.

A still from IT WAS JUST AN ACCIDENT

JP: The most important thing, to me, when I’m casting, is the body and the face of an actor. The face has to match the character, and when it does match, you can get a performance out of anybody. You just have to find the way.

I was involved with a film—I had co-written the script and I was going to edit it—and sometimes visited the set to give advice. And Mariam Afshari, who plays Shiva, was the Assistant Director there. She was not an actor. But her face was exactly what I was looking for. And that’s why I chose her.

HtN: And where did you find the little girl?

JP: She’s a relative of the woman who plays the bride. I asked my crew if they knew of anyone with these characteristics, and the bride said she had someone. I told her to give the girl the song, have her memorize it, and then videotape her while she’s singing and dancing. And when she brought the film and I saw she was comfortable with the camera, I said, “Yes, that’s her.”

HtN: You are free to travel now, it seems. Are there any restrictions on your filmmaking? What is your personal situation in Iran like right now?

JP: As soon as we entered Cannes, I said that when the festival ends I’m going to return to Iran. And I did return, meaning that 24 hours after the ending ceremony, I was in Tehran. After a while, I went to the Sydney Film Festival, and that’s when the Twelve-Day War broke. The flights were canceled and I could not go back. As soon as the flights were resumed, I went back on the first or second plane that flew to Iran. I stayed some time and then again left for some festivals. I had to come to the United States six times and there is no American Embassy in Iran. Every time I want to come to the U.S., I have to get a visa because they only give me a single-entry visa, and it takes a lot of time. Given that I have to travel around the world, I don’t have much time to go back to Iran. (laughs) I’m just praying for the day that the U.S. rejects my visas so that I can go back to Iran and breathe a little.

HtN: Inshallah! Thank you so much for talking to me.

JP: Thank you.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)