From REPO MAN to DEAD SOULS: A Lifetime in the Cinema of Alex Cox

REPO MAN (1984)

[the latest edition in an ongoing Curbside Criterion saga]

or

From REPO MAN to DEAD SOULS: A Lifetime in the Cinema of Alex Cox

“Lattice of coincidence… all part of the cosmic unconsciousness…”

In the pantheon of debut feature-lengths, Repo Man should be considered the Citizen Kane of 1980s punk rock films. Dare you to disagree? Like Kane, writer / director / occasional actor Alex Cox assembled a courageous crew of new-to-filmmaking individuals (along with an old-hand cinematographer, Robby Müller, as his Gregg Toland) combined with a memorable cast and made an astonishingly inventive film that continues to inspire audiences many decades later. Also like Kane, Repo Man follows the progression of its titular-ish protagonist from boyhood to manhood, albeit within a shorter time-span and with [spoiler] the bodies of extraterrestrials in the trunk of an automobile as an ersatz… Rosebud? Not precisely.

From its opening moments, authority-figures still haven’t deduced that the times have changed (or, at least, continue a-changin’). A traffic cop pulls over a Chevy Malibu with New Mexico plates driven by shifty J. Frank Parnell [Fox Harris].

“What’ya got in the trunk?”

“You don’t want to look in there.”

He shouldn’t. But he does.

Meanwhile, sex and drugs and rock-and-roll are made manifest amongst the aimless teenagers on the fringe of Los Angeles. Otto Maddox [Emilio Estevez], all of eighteen but passing for twenty-one, loses his job at the local supermarket. He pitches his inattentive parents about returning to higher education but they’ve given all of his promised tuition to a televangelist. A chance encounter with Bud [Harry Dean Stanton] lures him into his first automobile repossession. Back at the repo lot, Otto meets an assortment of oddballs under its employ, including Marlene [Vonetta McGee], seemingly the only sane member of the staff, and outcast / quasi-prophet Miller [Tracey Walter]. Otto reluctantly becomes a repo man as well, learning the trade from Bud (who seems to relish his new role as mentor of a wayward youth). In the midst of one of Otto’s subsequent repos, he unexpectedly meets Leila [Olivia Barash], on-the-run from Agents B, E, S and T, and she flees with Otto to the United Fruitcake Outlets. UFO, nudge, nudge! They pair-up, casual-romantically, but Leila then pairs-up, pseudo-professionally, with Agent Rogersz [Susan Barnes], a mysterious governmental operative with a metal hand.

Everyone wants the Malibu and the contents of its trunk. The repos eventually find it. A rival duo of repos steals it. A few folks are tortured in an effort to get the automobile back. All in all, though, why do they want this vehicle and its glowing contraband? What do they hope to achieve by getting it? Whatever their intentions, they’re about to become very disappointed with the price of their desires and an outcome… out of this world!

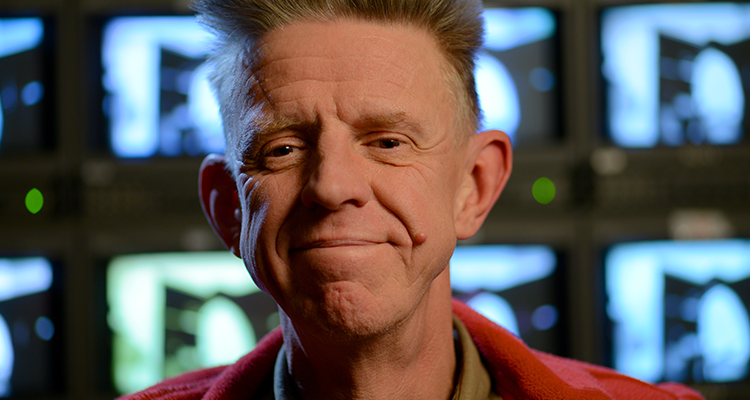

A still from REPO MAN

Admittedly, nothing about Repo Man is customary. Ice cubes fall from the sky! An irradiated vehicle glows negative in a positive-space! Even the end-credits go top-to-bottom! Plus that soundtrack… that glorious soundtrack!

With a new 4K transfer and a Criterion Blu-ray / UHD reissue on the day-after-Labour-Day, writer / composer / occasional filmmaker Jonathan Marlow spoke to Cox about his first feature and, coincidentally, his forthcoming “last” aka My Last Movie or Dead Souls or whatever it happens to be called when it is released.

[Bracketed commentary and embellishments below are the handiwork of the interviewer.]

Hammer to Nail: Appropriately enough (for a conversation ostensibly regarding Repo Man), I am ringing you from a parked car in the middle of nowhere (since there is no signal out in the wilderness). We’ll also discuss your forthcoming opus, your—supposedly—last. Beginnings and endings, potentially! You’re done, then? You’re finished with this pesky business?

Alex Cox: Or is it finished with me? I mean, the day I die [is the end].

HtN: As I’d figured. As for the opposite swing of that proverbial pendulum, I am pleased with the existence of this Criterion release, cobbled together from earlier editions…

AC: It is largely the same as the previous one, as far as I know. It is a different transfer! They’ve done a higher-resolution transfer.

HtN: What was your process for pulling everyone together to make Repo Man? You came to Los Angeles and, quite some time later, you assembled a miraculous team in terms of casting and crew and getting cinematographer Robbie Müller to shoot your debut feature-length. It seems as if lightning struck, poetically, for all of these things to occur at that one particular and peculiar moment.

AC: I was just lucky with the producers, Peter McCarthy and Jonathan Wacks. We had met at UCLA as graduate students. Obviously, everybody at UCLA wanted to be a director but I had to persuade them that they could be producers and we could do a film together. It was really their brilliance and perseverance that enabled it to happen… and also the discovery of [Executive Producer / ex-Monkee] Michael Nesmith, who took the film to Universal and managed to get the money to make it.

HtN: Right. [In the wake of the self-produced Elephant Parts “video-album” and its subsequent success, Nesmith became involved in a handful of unusual films throughout the 1980s. See also: Tapeheads.] Was the involvement of Universal at all contingent on getting a recognisable actor such as Harry Dean Stanton in the film? Or was much of the cast already pulled together by that point?

AC: It wasn’t contingent on Harry Dean. There was a lot of resistance to Harry Dean because he was viewed as merely a character actor. At one point, I went to meet Harry Dean’s agent at CAA (or wherever it was) and the guy says to me, “Harry Dean’s passé! You don’t want to use Harry Dean. How about Mick Jagger? I represent him, too!” Nobody wanted Harry Dean except for me and Peter and Jonathan. But we were very supportive of Harry and really wanted him to get his name above the title. It was the first lead-role he ever had! Then, as a result of Robbie Müller meeting him, Robbie called Wim Wenders on the telephone and said, “You know that you’ve been thinking about Dean Stockwell to play the lead in this movie you’re going to make…

HtN: Paris, Texas.

AC: They were going to start shooting just a few weeks after we finished Repo Man. Robbie said, “Maybe you should check out this actor, Harry Dean Stanton.” Indeed, he did. Wim gave Harry Dean the lead in Paris, Texas and relegated poor Dean Stockwell to a supporting role.

HtN: You wrote the script while you were in Los Angeles. Did you start it while you were still in school…

AC: Oh, no. I was done with school. It was a few years later…

HtN: Of the many directors who have been working since the 1980s to the present, you—far more than most—have a sincere and expansive knowledge of film. A real appreciation and fascination with a diverse assortment of films. All kinds of films, from the earliest to the latest. Westerns, films noir and all the rest. I’ve always adored the time-folding aspect of Repo Man beginning where Kiss Me Deadly ends. The mysterious, irradiated MacGuffin and the transformations of the characters surrounding it. It is fairly fascinating.

AC: There were a lot of cinephiles in Los Angeles at the time. I remember I went to see Kiss Me Deadly on a double-bill or something and Kareem Abdul Jabbar was in the line outside to see it. You know, a lot of people in L.A. were very film-literate. Really into movies. Of course, there was the Fox and the Nuart. There were all of these art houses in the city back then.

HtN: There is a feeling in the air of that period, not just in Southern California but in every corner of the world, of the then-latest manifestation of a nihilistic youthful viewpoint. In this case, it surfaces in the punk rock scene of Los Angeles. [I am biased, of course. In a parallel universe, perhaps there exists a version of the film set in the Bay Area of that era instead.] It seems as if you really tapped into a moment that few other films were really grasping at that time, seemingly in a lingering shockwave of an earlier expression of nihilism in Easy Rider. There are a handful, all of which have more or less became cult favorites—Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains or Suburbia or The Return of the Living Dead, perhaps—but I always think of Repo Man as being a primary catalyst for a convergence [even if it premiered a year-or-two after two-of-those-three], because the Otto Maddox character is an otherwise stereotypical teenager-transitioning-into-adulthood. Despite the corrosion of the usual pathways of conformity, circumstances push him to end-up taking a [air quotes] “serious job” by becoming a repo, learning the ropes from his considerably older colleagues, all rather jaded.

A still from REPO MAN

AC:…and it is all in the context of the likelihood of a nuclear war. It was in people’s minds at the time. There was that television mini-series called The Day After and then there was Miracle Mile, made around the same time [or a couple of years later than Repo Man], about the last moments before the bombs land. There was definitely a kind of a real concern that [Margaret] Thatcher and [Ronald] Reagan were going to get us in a nuclear war with Russia. Ironically, though, Reagan had a moral sense. Amazingly, in retrospect, you look back at Reagan and he knew that nuclear weapons were a great evil (as opposed to the clown-crew that now run the show). All of that was the context for the film.

HtN: Was the design for the credit sequence—a faux-computerized grid of the Los Angeles area—something that happened after everything else was shot? Or was that already thought-out?

AC: That was all done after the film was shot. It was the idea of Bob [Robert] Dawson who designed the credits and later became a major credit-designer. I think that was his first credit sequence. [It was!] Maybe he’d done credits on the student film before but that was the first feature where he did the credits.

HtN: How did you find much of the cast? The thing that remains remarkable after all these years is how there are no incidental characters in the film. Everyone has a well-defined and thorough personality. Every role is brought back into the fold at some point. There are no disposable characterisations anywhere throughout the film.

AC: The casting director was a woman called Vickie [Victoria] Thomas. She had been at UCLA and it was her first feature. She said, “What am I going to do on your film, Al?” I said, “Well, I’ve already got a director. Why don’t you be the casting director?” She cast the movie and then, of course, she became a notable Hollywood casting director who had done many, many films [and television].

HtN: It was largely an open-casting process to find folks like Olivia Barash?

AC: I think we put an ad in the Hollywood Reporter or something for auditions. There was no internet, right! I saw who showed-up.

HtN: Were the repeatedly resurfacing Pik-‘n-Pay generic products in the original script?

AC: That wasn’t in the screenplay. We tried to get product-placement for beer. We thought that we’d get a whole bunch of Mickey’s Big Mouths for free and feature them in the film. When they turned us down, it was like an act of rebellion against product-placement. Generic, it was!

HtN: It has aged very well.

AC: Ironic, too, as it ended-up being product-placement for Ralphs supermarket. They came up with their generic products at exactly the same time. They did it. We were impressed! The only things that we had to create were the cans that said “Food” and the cans that said “Drink” but everything else…

HtN: The rest were actual off-the-shelf products?

AC: They were real. They’re all from Ralphs! The “Food” and the “Drink” cans were Harry Dean’s idea.

HtN: It makes sense. After their various repossessions, he kept saying, “Let’s go get a Drink.” In your mind, how does “Drink” taste? What flavor is it?

AC: Whatever flavor you want! It’s some kind of canned-cocktail, isn’t it? It might be a Mai Tai or… I don’t know. It’s some sort of alcohol and chemicals.

HtN: Some flavoured chemicals. Definitely. There are many lovely little touches throughout the film. Obviously, a disproportionately substantial amount of clever dialogue as well. Very quotable moments. “I know a life of crime led me to this sorry fate… and yet, I blame society. Society made me what I am.” It seems like a script that you would have truly enjoyed writing.

AC: Many of these were things people actually said to me. All of the stuff that Harry Dean’s character [Bud] said to Otto was said to me by various repo-men. The Tracy Walters speech about alternate realities and the stuff about going to John Wayne’s house and installing two-way mirrors, a guy told me he’d done that. A guy who was at a glass company in Ocean Park insisted that he’d been to John Wayne’s house to install two-way mirrors and that John Wayne came to the door in a dress.

HtN: I had not imagined that there was a basis of reality in that conversation.

A still from REPO MAN

AC: That’s what he told me! He insisted it was true and there were other witnesses present. A lot of it was just things that people had said to me when I was in the repo car and stuck in my head. I would write down everything that repo had said.

HtN: Is the location for the repo lot something you’d found during your research?

AC: We just found [through Mark Anderson, Location Scout] a nice lot in the city of Vernon, south of downtown, where most of the film was shot.

HtN: A passing bus has an Edge City* moniker on it. Is the idea that this is all taking place in this speculative zone of Los Angeles? *[Edge City aka Sleep is for Sissies is the name of Cox’s first film, a short made while he was still a student at UCLA.]

AC: I think Otto lived in the Valley and I believe we shot that scene [with the bus] in the valley. I think that is the only thing that we shot in the valley. Everything else is almost all downtown or near downtown.

HtN: You can see downtown L.A. in the distance in several scenes. It sets a mood for the mid-‘80s Los Angeles. Obviously, downtown is a bit different these days…

AC: There were four or six skyscrapers. Now there are more!

HtN: Repo Man is a film that is placing itself firmly on the fringe of civilization.

AC: The Los Angeles River was definitely a choice location because it is in Point Blank and it is right there.

HtN: It is a great, great location.

AC: It is beautiful. You can’t not do that!

HtN: It serves as a great set-up for the scene with the Rodriguez brothers. Meanwhile, when Fox Harris first appears [as on-the-run Malibu driver J. Frank Parnell], there is an aspect of his performance that reminded me of Dennis Hopper.

AC: They knew each other. They were all part of the same circle. Harry [Dean Stanton] was part of a big, wide circle as well. He was from the Actors Studio and, of course, Dennis was supportive of the Actors Studio and Harry Dean. I knew Fox because I’d been a caretaker of the Actors Studio in Los Angeles. A woman called Nancy Richardson [film editor and, later, professor at UCLA] and I were caretakers there for a while and the actors were really mean to us. They wouldn’t talk to us and they stole our food. We put a padlock on the fridge and they broke the padlock to steal our food. The only person who didn’t steal our food and talked to us was Fox Harris. You remember these things and then, later in life, you get to reward the good behaviour.

HtN: It seems very forward-thinking to have already imagined that a natural progression for this “out there” music would be its eventual commodification. It was inspired to have one of the bands play a lounge-version of themselves. I imagine that Keith Morris and the rest of the Circle Jerks were happy to satirize themselves in that way?

AC: Oh, yes. They’ve got a very good sense of humor…

HtN: How did you connect with them? How did you connect with any of these bands?

AC: I went to see a lot of punk shows. I often went with Dick Rude [who stars as Duke in Repo Man and resurfaces in other roles throughout Cox’s career]. We’d go see them all. We’d go see the Weirdos and Suicidal Tendencies and Fear and other acts.

HtN: What was the initial appeal of the U.S. prior to attending university?

AC: I wanted to work in the film industry and the British film industry was very small and very domestic. You really couldn’t get a card to work or to be in the union unless your father was in the industry. Or if you went to the National Film [and Television] School [NFTS] in Beaconsfield for three years. Beaconsfield is on the outskirts of London and I didn’t like London. I didn’t want to spend three years there. Instead, I got a full-ride to go to UCLA for a year. I just stayed.

HtN: Which was a good idea in the end.

AC: It worked-out okay! I mean, the English film industry probably hasn’t changed much at all but it is interesting how much more nepotistic the American industry is now. Probably, inevitably, because of the limited number of jobs that are actually available and the fact that wealthy people tend to have children.

HtN: It has become very incestuous in that way.

AC: Much more so than it used to be. The Mexican industry, too. Crews get bigger but they don’t get more efficient. They get bigger to accommodate all of the extra children that people have had but they don’t get more efficient!

HtN: After the many-year slog of working within the confinements of “traditional Hollywood cinema” (if you’d even consider it that way)…

AC: I was never in the “traditional Hollywood cinema” because the only films I made for studios were made as negative pick-ups. The studio read the script but they didn’t have any involvement until you delivered the finished film. Then, if the finished film was a fair facsimile of the screenplay, they had to pay. You just had to find some wealthy person who could take out a bank-loan to cover the production until the studio bought the picture at the end of the production.

HtN: There is not much of that happening these days.

AC: I don’t think it is done anymore. I’m not aware of it being done anymore. What the studios were doing in those days—in the ‘70s and the ‘80s—they were learning how to make independent films. They were learning how it was done because they wanted to get around the craft-guilds. Once the studios figured-out how an independent film was made, they created their own faux-independent companies, like Focus Features. They made their own.

HtN: More recently, many of the streaming companies did something relatively similar. They were acquiring films that were made on spec for a few years until they built-up their own in-house facilities to do the same work. It is unfortunate (since we’re right back where we started).

AC: It is interesting. Also, for independent films, COVID was a very big problem because it added additional difficulty and expense. Protocols that had to be observed. The doctors and nurses. You had to be very careful on set. All of that stuff added a considerable amount of money to the budget. If you’re making a very low budget film, it was very difficult.

HtN: Given our mutual love for The Prisoner—yours, more evident, because you wrote a book about the series—I find that Repo Man and your other films evoke many identical concerns. One of the details that captured my imagination as a child was the notion that the opening sequence of The Prisoner tells you much of what you need to know and more than you’re immediately aware. In particular, the notion of “information” as the “in-formation” of obedience. That falling-into-line. I find Repo Man to be an ‘80s theme-and-variation of a ‘60s television show, existing within the forces at-play to persuade individuals to conform to whatever society wants them to become. The whole film (and all of The Prisoner) is rebelling against that direction, even to the very end.

AC: I am sure you’re right. The Prisoner was the most amazing thing I ever saw on television. I’m sure that it stuck in my mind. I’m sure that it was always there.

HtN: The concerns that Patrick McGoohan had for creating the series are concerns which are shared by anyone upset and disturbed by the direction of society at any particular moment. Where the powers-that-be are trying to push society in one direction or another for the benefit of the few. The ease, for instance, at which individuals are willing to go to war or engage in conflicts. These people who make those decisions do not generally suffer consequences directly.

AC: It is easy for them to fund conflicts very far away as long as we don’t have to go and get killed in them. The U.S. government or the U.K. or the European Union… Not that anyone is paying the bills for the war in Vietnam or the war in Iraq or Afghanistan or the war in Ukraine or the war in Gaza. They just pass it on to Lockheed Martin.

HtN: There are far too many corporations benefiting from never-ending wars. [Granted, more-than-one is already too many.] Connecting Repo Man to your forthcoming film, Dead Souls or My Last Movie or whatever it will be called…

AC: My Last Movie is the name of the campaign to raise the money. The film will have a different name.

HtN: That is what I’d suspected. Title to-be-determined!

AC: We’ll see what it is called when it’s done.

HtN: Does that the same sense of frustration with society permeate the new project? As it seems to be a subtext in all of your films that I have seen (which is, essentially, all of them).

AC: I was talking to one of the actors last week and he said that he thought that the theme—or what united all the characters in the script—was desperation. That is actually a good observation because certainly the protagonist is motivated by desperation but it hadn’t occurred to me that all the other characters were as well. It is a little different from the book in that sense because not all of the characters are desperate. I mean, [Pavel Ivanovich] Chichikov in the book is desperate. He wants to acquire a whole load of serfs to advance himself in society. [spoiler] He is going to conceal the fact that they’re dead, though. All of the people in the script are kind of past the idea that they’re going to advance in society. It is a more existential struggle and they’re engaged in that.

HtN: What are the advantages of taking the novel Dead Souls and putting it in the milieu of the Western? Not that I’m disagreeing with the notion.

AC: It is interesting because the author [Nikolai Gogol] was considering it as the first part of a trilogy. There were supposed to be three Dead Souls books. The first one was about bad people. The second was about good people. The third one was to be about paradise. But he only ever wrote the first one. He had two attempts of writing the second and tore them up and burned them. Only fragments remain. He never started the third book at all. It is obviously easier to write about bad people than good people! Naturally, it lends itself to a cynical tale told in the American Southwest in 1890. It is also an excuse for me to go to those locations. I love those locations! I love to go to Arizona. I love to go to southern Spain and be in that desert. Making a film affords you the opportunity to do that.

HtN: You’re saying that you write your scripts based on where you want to be?

AC: Definitely. That is why I made Walker. I wanted to make a film in Nicaragua! We made Repo Man because we were in Los Angeles. We had to make a film in L. A., you know?

HtN: Not Antarctica, presumably.

AC: No. I’m not going to Antarctica. No. I’ll leave that for others.

HtN: This experience of crowdfunding [full disclosure: these two fellows collaborated on Tombstone Rashomon not quite a decade ago, although the contributions of the interviewer were of modest proportion compared to the efforts of the interviewee], how has it been for you overall? Do you feel like these nontraditional routes of film-funding have given you a considerable amount of freedom?

AC: It has been the most amazing response. We made more money than we expected and I think everybody was surprised. Even Kickstarter seemed surprised. They weren’t expecting that we would get as good a response as we did. It was very encouraging!

HtN: To what do you necessarily attribute that success? The common routine is that recent crowdfunding campaigns have found it harder to generate comparable interest than in the past. Early-on, many people had great successes and then found it more difficult to go back to that well in subsequent campaigns.

[Though the campaign ended, you can still belatedly support here.]

AC: Surprisingly enough, we’ve inverted it. I think it has to do with people being cineastes, like Kareem standing in that that queue to see Kiss Me Deadly. They want to see what they want to see. For the Kickstarter campaign, more people wanted the DVD or a Blu-ray than wanted a streaming film. A lot more people are interested in the physical-good itself.

HtN: It is a pleasant change that folks see the value in having access to something when they want rather than relying on some third-party to provide it.

AC: Relying on some corporation to host the thing online or having to pay a monthly fee just to be able to access films that you like. Why not go and buy the Repo Man DVD?

HtN: Exactly right. For this production, you’ve brought some of the usual suspects back together, like Phil Tippett and so forth.

AC: Many people. Some of the actors from Repo Man. Some of the actors from Tombstone Rashomon. Crew from all over the place. One crew in Spain and another crew in Arizona. The Spanish crew is all firmed-up. We shoot in October. The Arizona crew is still coming together because people in the industry are hoping that some big projects will suddenly happen in the fall. We have some time, though. We will be shooting there towards the end of November. We don’t need to be crewed-up yet.

HtN: You should have a firm grasp on the direction of things after the Spain shoot.

AC: Once all that is in the can, so to speak. That should make everything clear.

HtN: In the meantime, everyone can buy Repo Man again after having already bought it in the past. Just as late-stage capitalism intended.

AC: If they just bought a new 95-inch television set…

HtN:…this would be just the film for a test-drive.

REPO MAN (1984)

dir. Alex Cox [92min.] Edge City Productions | Universal Pictures | Criterion Collection

– Jonathan Marlow (@aliasMarlow)