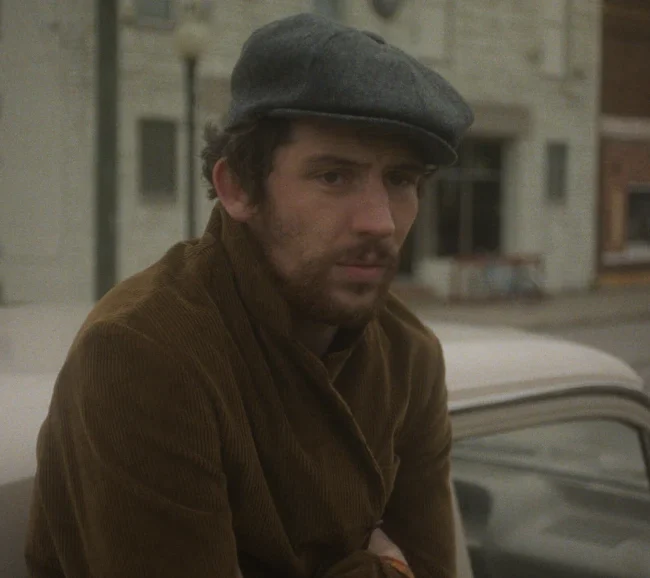

After only three features, Ramin Bahrani has quickly established himself as one of American independent cinema’s most accomplished new voices. His first two films, Man Push Cart and Chop Shop, were social realist tales featuring marginalized characters living in New York City—the type of characters that most movies ignore or brush off into the background. For his third, Goodbye Solo, Bahrani left New York City behind in order to return to his roots in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Goodbye Solo tells a bittersweet tale of a Senegalese cab driver and an aging Southerner whose paths cross unexpectedly, leading to a connection that neither one of them could have predicted. Goodbye Solo stands as one of 2009’s most affecting achievements, a story that is told with both clarity and simplicity. As Bahrani mentioned in our following conversation (though it unfortunately didn’t make the final cut), he wanted to make a movie that our moms would enjoy but that cinephiles would appreciate as well. He succeeded and then some. Days after a MoMA retrospective that featured a preview screening of Goodbye Solo just weeks before its official release (on Friday, March 27th), I sat down with Bahrani to discuss his filmmaking process, the inspiration for Solo, and the general state of the industry. (Visit the film’s official website to learn more.)

H2N: Having made two extremely well received low-budget features, and now on the cusp of the theatrical release of your third, how do you feel about your career trajectory at this very moment?

RB: Pretty lucky to some degree. I don’t think luck is everything but I think it’s always a part of something. There’s obviously a combination with a lot of hard work and great collaborators and selecting subjects that seem to reach someone, but I think part of it is also being fortunate that somehow the films struck a chord initially with festivals and then with critics, they got them enough support to get bought by a handful of distributors and seen by a handful of people. I also feel really lucky that the films were made so quickly. Looking back on it now, like you’re saying, if we were sitting here and talking about Man Push Cart, I really don’t know how I’d be able to make another film now, in this environment. And not just economic environment, in a cinematic environment where Ken Loach’s film isn’t necessarily guaranteed theatrical distribution. Who am I? This is the world we’re living in. We’re living in a world where Saraband played for like two weeks at the Film Forum. Ingmar Bergman! Two weeks! What?! And it’s actually a really good film. So, after each film I really could feel the door slamming on the back of my foot. Like, “That’s the last chance you’ll get! Behind you they’re not gonna have a chance anymore.” So, I’m extremely lucky that for some reason we made them so quickly.

H2N: Are you having any pre-release jitters with regards to Goodbye Solo, that impossible, but unavoidable, stress of “will the people come?” Is that something you’re troubled by, or are at least weighing, or do you have a handle on how crazy the world is right now and have a measured perspective with regards to how far out of your hands it actually is?

RB: Economically, or in just the world of cinema?

H2N: In the world of cinema. Just thinking about that opening weekend, March 27th.

RB: Of course I’m aware, I’m aware of what it should do, I’m aware of what we’re hoping it’s going to do. I’m understanding more by working with distributors on the three films. I’m in close contact with Dusty (Dustin Smith, Director of Acquisitions) at Roadside and trying to learn things from him, what they do just so I know better.

H2N: Dusty’s great.

RB: Really great. And I understand, he’s looking at what other films are coming the week before, the week after, and I’ve come to understand how important that can be also. I didn’t understand how much all the distributors are looking to make sure they don’t put similar films that may attract similar audiences or similar responses from critics at the same time, whenever possible. And I think that’s important for all the films. I haven’t seen Sugar yet and I’m looking forward to it and I’m sure it’s gonna be a really great film, and I think the audiences that like my film will like their film too. So it makes sense for us not to have an opening on the same weekend.

H2N: That would be a bad idea. They’re very different but it is the same audience.

RB: Cinephiles who have seen their first film or have seen my two films probably are gonna want to go see both. The critics, hopefully, are gonna support both. It’s interesting. I mean, you don’t think about it when you make a film. I think it’s important for filmmakers to know at least a little bit about these things. You just don’t want it to affect you creatively. Picasso’s always a great example of that. Great businessman, great at marketing himself, but he never let it impact his work and kept that separate.

H2N: It’s a corny question, but I always want to know how closely the finished film resembles the shooting script.

RB: It’s close. It is the closest of my three films. Man Push Cart, the assembly was two-and-a-half hours, and it’s an 80-some minute film. With Chop Shop, the assembly was like an hour and forty-five minutes and it’s an 80-minute film. But scenes were really rearranged at times. Like actions that I thought would happen in the first act happened in act two, or vice versa, and it changed the meaning of the film. Here, not much was rearranged. Certain things were just jettisoned. The girlfriend, Solo’s ex-girlfriend, actually was his girlfriend in the script. He was cheating on his wife during the course of the film, and he actually broke up with his girlfriend during the course of the film. She got cut out of the film and became an ex-girlfriend. But they’re still kind of flirting with each other, which we liked. The drug dealer character had a couple of scenes cut. Things like that. But basically it’s the same. Maybe there was something like where to express something in the script took two scenes but in the film one was enough. Solo cleans the room, William is moved by that somehow and he looks at Alex’s photo. In the script, he actually went to the Laundromat to see what Solo was doing in the Laundromat and started helping him study there. It wasn’t needed. When you see the film, it’s so clear: he’s been moved and he’s gonna quiz him later anyway. Better to be efficient. I edit the films and I’m the first to cut.

H2N: I wanted to talk about that as well. Whenever I see the edited by credit is the same as the writer/director, I flinch a bit. But with Solo especially, it’s always moving but it feels precise and lived-in. It breathes but it doesn’t feel indulgent. What kind of eyes do you get in the editing room? Just a few?

RB: Mike Simmonds and my co-writer (Azimi Bahareh) are the closest people. In Push Cart, Simmonds came to the apartment for like five days in a row all day. My co-writer would come from France for two weeks to look at the editing process. So these two are the closest. And then there are a handful of people that know me, that know the projects and that are watching.

It’s a long process. You may pick and then you may have to go back and pick again. I like to try all the possibilities. Everything’s open. I’m not affectionate about the footage. I’m quick to cut things that aren’t necessary, things that aren’t good.

H2N: Have you always been that way? Or is that something you learned?

RB: No, I was that way with Push Cart even. Better to make them as efficient as possible. But that doesn’t mean short, in terms of you can allow things to breathe. Editing is really strange. There was a time close to the end of the editing process in Solo that the last half was working perfect. Pacing, feeling. The first half wasn’t quite right. And it felt too long and too quick. So things got removed and what remained got lengthened. Made all the difference in the world.

H2N: Music’s another one I wanted to ask you about. Speaking specifically about Solo, you don’t have a score but you use source music in a creative way where it acts as such but it’s also rooted in the world on screen. So it provides variety, but in a way that is honest within the story. Beyond that, the fact that Solo is aware of his passengers’ musical tastes is such a great roundabout way to establish his character’s sensitivity and warmth.

RB: The guy that I spent six months driving around with in Winston, the cab driver, who was really charming and really friendly, he was all these things. He was also, like Solo in the film, good at matching the person in the cab. So if his drug-dealing buddy got in the cab he was quick to switch it to rap. If, sometimes an elderly African-American lady got in who was interested in R&B or gospel, he would change it to R&B or gospel for them.

The real guy, no one could leave his cab upset. I remember one story specifically where we picked up a middle-aged woman who had to work her second shift cleaning an office space. She was coming in for like the five o’clock shift to clean it up. And she was really agitated. We were a little bit late picking her up. She was very busy, tired, clearly, and was agitated. And, the guy I was with didn’t like to be known really. She was upset because he wasn’t her normal driver, and she claimed he was going the wrong way. And by the time we got there he had made her laugh, smile. Not only that but he kept charming her like, “You’re looking beautiful today, Honey,” or, “You’re lookin’ nice, Sugar,” weird things that we might think, “That’s not right! That’s sexist!” No, it really helps the situation for what’s going on, and he just kept knocking the price down. He was like, “Well, what do you normally pay?” “I normally pay this much.” “Great, you just pay me that, I can turn off the meter right now, or we can have the meter go and you can just pay me less, I don’t mind.” And she couldn’t believe it. And he kept kidding with her and before you know it she’s back there laughing. You just can’t be angry with him. And I’m like, “Who is this guy?”

H2N: Was there any thought that you couldn’t make the movie without him?

RB: I almost canceled when he told me he didn’t want to be in it. I remember having finished Chop Shop and going back in March to Winston. I had to do some retouches to the mix in Chop Shop. I was like, “I’ll just go back to North Carolina for six weeks and find Summer (Shelton, casting department) and get the casting process started so that I can come back to New York and finish Chop Shop,” and we ended up getting into Cannes so I was gone for longer. But I had then already started the ground team as far as casting. I had someone there going to the schools, videotaping little girls for the part of Alex, so that when I got back work had been done. I remember going back and he said, “I’m not gonna do it.” I was devastated, I was literally about to throw the film away. I didn’t want to make it anymore.

H2N: Had he implied that he was going to do it?

RB: He had always implied that he was going to, and he knew I was doing it for him. The reason I did not cancel was my friend, who the film is dedicated to—Sandra Trujillo de Moyano—a close childhood friend of mine who had been terminally ill with cancer, she had been struggling with cancer for about six years, and had come back to live in Winston-Salem, and wasn’t doing great. And I got there, she was so excited that I was there, she was happy that there was another friend in town. She and her husband had been living in Costa Rica and now she had come back to be with her parents for treatment. She started coming with me to look for actors. We would start driving around the Hispanic part of town ‘cause she could speak Spanish. She’s half Colombian and her husband’s Argentinian. And she would talk for me, ‘cause my Spanish isn’t very good. And it was just so much fun doing that with her and she saw how upset I’d gotten. I looked at her and I thought, “How can I give up, how can I be upset, how can I complain in this moment when she just keeps having so much life in the face of death?” Which is what the film is about! And I felt really ashamed with myself and I knew I had to make the film. I couldn’t look at her and tell her I wasn’t going to do it.

H2N: Getting back to what you said at the beginning, I want to get your take on the state of the film industry. Do you think it’s a freakish time and everything will settle down or are things changing irrevocably?

RB: You have to understand, in my opinion this question is about cinema connecting to a collective consciousness of culture. Let’s go specifically to cinema, and then that can be extracted to broader social things. If Jim Jarmusch were to be making his first film today, he would be as well known as me. By which I mean to say, he would be not one of five filmmakers, he would be one of 500 filmmakers. He would be one of 50 filmmakers that the critics like that year. Not one of five. So then, the attention that those films got in that time period gets divvied up into a lot of good filmmakers: Kelly Reichardt, So Yong Kim, Ira Sachs, Phil Morrisson, Craig Zobel, et cetera. There are so many of us now that are making quality films that we can’t all go to see the same one. And the one that we all do go to see is the one that has massive marketing behind it, which tends probably to be the film that we don’t want to talk about. I’m not gonna have a conversation with you here about Juno. I just don’t want to talk to you about it. And then there are a handful of good ones that we do want to talk about that everyone goes to see like There Will Be Blood, which was made by a mini-studio and cost 25 million dollars to make but it had 70 million dollars to market.

You can take that into a cultural setting by saying we’re not all gonna watch the same sporting event. We’re not all gonna read the same newspaper anymore. We’re not gonna all read the New York Times ‘cause now I want to read Hammer to Nail. “Oh, I don’t wanna read Hammer to Nail, I wanna read Eye on Cinema.” “I don’t wanna read Eye on Cinema, I wanna read the Austin Gay and Lesbian Film Guide.” And I’m not saying those things shouldn’t exist. I’m not here to say they should or shouldn’t be. They are. And that divides up where people go to seek information, divides up what they actually watch on television, what sporting events they watch, what films they see, what books they read. Everyone can’t watch the World Series anymore because someone wants to watch curling on channel 593. (H2N laughs) So that person’s not watching the World Series anymore. And that means there can’t be the same massive cultural dialogues anymore, without weird exceptions or massive campaigns. Slumdog Millionaire, would that film have been that film if it had not been distributed by that company with that massive machine around it? So, I think that’s part of it. The rest of it? I don’t know. Is cinema as important as it had been? I just don’t know.

H2N: Are you daunted in any way? Goodbye Solo is the type of film that made us start this site in the first place, but if the film comes out and doesn’t connect, is your spirit and commitment to being a filmmaker enough to keep you going?

BR: I don’t want to give a coy answer but I just don’t know what else to do. That’s one part of it, which I know a lot of artists and filmmakers say but it’s kind of true. What else am I gonna do? Plus, I have three things I want to get back to once we finish talking. Look, I deliberately made it hard on myself. It is not by accident that I haven’t worked with actors, that I picked these subjects. There are a lot of reasons why. I’m interested in them. I thought these voices had not been seen or heard before. I personally get excited learning about things I don’t know about, et cetera. Another reason is, just excluding the personal, emotional, philosophical, artistic reasons, as a craftsman, I wanted to make three films, and I did make three films, that have made you want to sit and talk me. The films are not about anybody famous, they do not star famous people, there is practically no music, the camera is not show-off-y, there is very little “cool style” to them, there’s just nothing. There’s a guy putting coffee and donuts in a cart, there’s a kid in a garage that you never heard of before, there are two guys that you’ve never heard of who had two working-class jobs and none of them are actors. And I don’t explain a lot of stuff. And you still want to talk.

H2N: When those three characters, near the end of Goodbye Solo, are ascending the pathway at Blowing Rock, at that moment the film just transcended for me. You managed to pull that off without any artifice whatsoever, which made it all the more exhilarating.

RB: One, two, three. Old, middle, young.

H2N: Yet you didn’t hit us over the head with that. Solo on the rock with the stick is technically the climax, but for me, that shot of them together was when everything came together. Mercifully, it didn’t feel like you were “talking” to me.

RB: The political and social statement of the three films is: a lead character is a Pakistani pushcart vendor, a lead character is a Latino street orphan, a lead character is a Senegalese cab driver. For me to then comment on it, and show you exotic food and cool culture and funny clothes, is to ruin it. And it’s to betray Edward Said and everything that he tried to do in his life. And we move beyond that. I’m not a visitor. My film is not about a visitor. I made an American film. And I have my right, the same as the characters in my films have their right. And what makes them outsiders is, first and foremost, their economic position—which now everyone is feeling like that—and their consciousness as people. Consciousness as a person makes you an outsider. It makes us an outsider to everything that surrounds us, in terms of the machine of the world, be that in any way you want to take it: religion, money, capitalism, commerce, whatever. Once you wake up and things change you become an outsider, and these three characters in all these films, even William is an outsider. William is more of an outsider than Solo in this film. He belongs less in his own hometown than Solo.

H2N: A last question, which struck me watching it a second time the other night. After the first viewing, I was left with not as much sadness, there was still a sense of hope and Solo’s smile is what remained with me two days later. And then watching it this time I thought, “This is a sad ending!” It was almost a totally different reaction. My appreciation of the achievement hadn’t changed, it may have even gotten stronger, but as for my visceral emotional reaction, it was quite different.

RB: Endings are weird. I’ve been thinking for months about the ending of Cool Hand Luke. A lot of times when you talk about the film, people are like, “Aw, Cool Hand Luke, the eggs!” and I’m like, “The dude got killed in the end!” And he became a legend and a myth, and everyone just went right back to their work. Nothing changed. It’s a really dark film. But you remember his smiling somehow.

The initial conception of Solo in the ending was that Solo would be laughing and crying at once. That life and death would become completely connected. That you would be left with both. I’m kind of excited that you’ve seen it twice and have had two different reactions. Of course he’s sad because of what’s happened, he’s stronger because of what’s happened, he knows that’s what had to have happened, Alex’s presence can’t help but give him spirit for the future, knowing that William thought he would pass (the flight attendant test), and now Alex is sitting in his place asking the same questions. It’s not that she’s just asking him the same question, “What do you do in a water emergency?” She also asks a first question: “What is XLV?” Extra Life Vest. Like you said, not hitting you on the head, but there’s always some small thing. The fact that he wants to study again and that she’s going to encourage him to do it, that we know deep down this had to be the decision, he had to do that, he knows it, and it’s really hard. That’s a hearty soup.

— Michael Tully