A Conversation With PJ Raval (BEFORE YOU KNOW IT)

The Hammer to Nail interview with PJ Raval takes place on the concave cushion of an elegantly worn couch at the Bourgeois Pig in Los Feliz; Raval pronounces it “very Austin.” He’s a rare combination of energetic and thoughtful, focused and friendly; for an artist, his outlook is unusually positive. He looks terribly young, but his IMDb page is as long as your arm, made up of shorts and docs (and a few narrative features as DP) of the very-independent variety. He’s won numerous awards for a body of work that largely (but not exclusively) focuses on LGBT themes and characters. He’s in town for the Outfest screenings of his new documentary about gay seniors, Before You Know It, as well the music video “Big Shot“, the latest in a string of beautifully deranged collaborations with Christeene, the underground “drag terrorist” persona of performer Paul Soileau.

Hammer to Nail: Since you’re a DP yourself, how did you think of Before You Know It in terms of telling the story visually?

PJ Raval: You know what’s funny is a lot of people ask me was it hard to let go of the camera, and actually no, it was not hard at all, and I think that’s part of me also working occasionally as a cinematographer. I feel like I understand the importance of that role, and I really wanted to be able to work with someone who I trusted, who I thought would also bring their own vision to it, so Mike Simpson, who is someone who I work with pretty closely—on several projects now—did a really amazing job, and with this film in particular I asked him to think about the way we’re capturing the subjects and the subject matter, and really think about things like youth versus aging, and how can we see that visually. And I really wanted him to draw upon elements of what I would consider more fiction storytelling, in terms of cinematography, so really being able to shoot something and think about it from a scene perspective. Not just capturing what’s in front of you—that’s almost the first thing—but the second thing is to also think about it now as a scene that’s unfolding. Like how would you capture this as a scene artistically? Not just recording it as well. So it’s a real challenge, and you know I’m a cinematographer and I’ve shot for other people who shoot so it’s always a little nerve-wracking, but he dove right in and did a fantastic job.

PJ Raval: You know what’s funny is a lot of people ask me was it hard to let go of the camera, and actually no, it was not hard at all, and I think that’s part of me also working occasionally as a cinematographer. I feel like I understand the importance of that role, and I really wanted to be able to work with someone who I trusted, who I thought would also bring their own vision to it, so Mike Simpson, who is someone who I work with pretty closely—on several projects now—did a really amazing job, and with this film in particular I asked him to think about the way we’re capturing the subjects and the subject matter, and really think about things like youth versus aging, and how can we see that visually. And I really wanted him to draw upon elements of what I would consider more fiction storytelling, in terms of cinematography, so really being able to shoot something and think about it from a scene perspective. Not just capturing what’s in front of you—that’s almost the first thing—but the second thing is to also think about it now as a scene that’s unfolding. Like how would you capture this as a scene artistically? Not just recording it as well. So it’s a real challenge, and you know I’m a cinematographer and I’ve shot for other people who shoot so it’s always a little nerve-wracking, but he dove right in and did a fantastic job.

With this film in particular I told myself I really wanted to step up the visuals, and I wanted to think about how I could create another visual layer, so when we finished filming most of the observational scenes, it’s something that I had decided early on that I wanted to try—we moved on to what I called the film portraiture section, and with that I really wanted to create this idea of a moving photograph, like the idea of a photograph being a document of a time period but something that’s moving and changing within the frame, and that idea that even if the subjects are still and posed, the world around them is moving. Whether it be faster or slower, you can’t stop the world from changing.

Along with that we shot some super-8 footage, and it really wouldn’t have been possible without the fact that I was able to get a grant from the Texas Filmmaker Production Fund [Ed. Note: Now called the AFS Grant], from the Austin Film Society, that came along with Kodak film. Back in the day I—actually not that far back in the day—but I actually have shot a documentary on film and it’s incredibly challenging, and I definitely recognize that a film like mine is hard to do on film, but I still love being able to incorporate celluloid into this process. Because so much of documentary and nonfiction filmmaking now is digital. And there’s so much about small-format video allowing nonfiction storytellers to run with it, which is great, but at the same time I’m really grateful that we were able to incorporate some kind of film element. And it was also really important to me because I just think the imagery of film—celluloid, grain, things like that—it also hopefully brings across the idea of things that fade. Unlike digital, which is a lot of ones and zeroes, film has a certain alchemy to it but it also has a certain nostalgia to it because it is something that’s hard to preserve and it’s something that degrades over time and it’s something that people equate with something a little bit more living.

H2N: Were there any common misconceptions about aging that you found to be inaccurate in the shooting of the film?

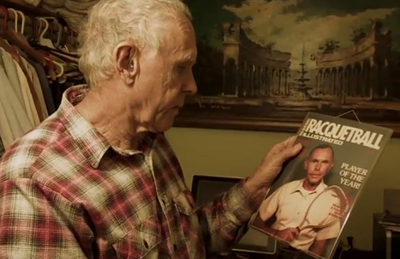

PJR: Absolutely. And a lot of it just ‘cause I’m misinformed and at times not even exposed to the stories or even the points of view of seniors or those in the aging community. One of the things I discovered, at least with the subjects that I follow, is that life continues to unfold. And one of the things that’s my fear of aging is that at some point you’ve seen everything, you’ve experienced everything, you know everything, you’re this wise kind of sage-like being—which to me,I find that incredibly boring, I find it incredibly stifling. It’s like there’s so much pressure, like how am I supposed to get to that point? And so I love the idea of seeing Dennis, for instance, who just turned 80 and he’s still in the process of discovering himself. And I think there’s something that’s really great, knowing that life doesn’t get stale, that there’s always more to learn, more to discover, not only about yourself but about other people, and the world is always changing. Even in your golden years.

PJR: Absolutely. And a lot of it just ‘cause I’m misinformed and at times not even exposed to the stories or even the points of view of seniors or those in the aging community. One of the things I discovered, at least with the subjects that I follow, is that life continues to unfold. And one of the things that’s my fear of aging is that at some point you’ve seen everything, you’ve experienced everything, you know everything, you’re this wise kind of sage-like being—which to me,I find that incredibly boring, I find it incredibly stifling. It’s like there’s so much pressure, like how am I supposed to get to that point? And so I love the idea of seeing Dennis, for instance, who just turned 80 and he’s still in the process of discovering himself. And I think there’s something that’s really great, knowing that life doesn’t get stale, that there’s always more to learn, more to discover, not only about yourself but about other people, and the world is always changing. Even in your golden years.

I think the other thing is that society likes to desexualize seniors. And I’m someone who’s very aware of my sexual identity, of who I am as a sexual being. Just by calling yourself gay or queer or anything you’re identifying so much of yourself. So I love the fact that so many of the seniors that I follow are sexually active, are still thinking very much in those terms, of sexual identity and relationships. And the common view is [these] people are over that. So it was inspiring to see that because [the way] I’m thinking now, why wouldn’t I be thinking along the same lines when I’m 80? I also think—we talk about it in the film—that the energy level is maybe not as high as it used to be, or maybe you’re not able to stay out as late or as long, and maybe you need to take more breaks or naps, but that doesn’t mean that the desire to be active is not there. So that was also really great to see. It’s not people who—at least the ones that I’m following—prefer to stay at home; they’re actually out in the world being adventurers, being really brave in a lot of ways. And it was also really great to see that a lot of them formed relationships with people and those relationships lasted and still continue on. And there is something about those relationships that we forge, and the ones that will continue, and the ones that stay with you, and I would love to think that some of those would be into my golden years.

I also discovered a lot of things which I was afraid existed. There’s a lot of discrimination, there’s a lack of support for senior communities. There’s a lot of estrangement. A lot of senior communities are overlooked, and people don’t wanna pay attention to them. And I think a lot of it is because people are afraid to talk about aging and accept the fact that as a young person you’re not immortal and you’re not going to stay in that physical state for the rest of your life, and that kind of power that comes with youth will fade over time. But a great way to start thinking about it is embracing the fact that it’ll change into something else. And there’s something great about seeing all the subjects that I’m following embracing that in terms of who they are.

H2N: So along those lines, and particularly in terms of Ty’s storyline, did you have a sense that there’s an inherent difference in the kind of partnerships that people form at that point in life as opposed to younger people?

PJR: Yeah, absolutely, and you have to keep in mind that I’m looking at a particular group of LGBT seniors. And what I mean by that is they’ve lived through a very particular time in history. So Ty’s a great example, where he says many of the people who he grew up with who he thought he would grow old together with, you know, they died during the HIV/AIDS crisis. So that was a huge change in terms of who his community was. You look at someone like Dennis and he, you know, “played the game” and remained closeted and just tried to maintain a life as a heterosexual man and got married. And he says it in the film and he’ll tell you himself that he very much loved his wife and he very much appreciated that relationship, but he recognizes that he’s always had tendencies outside of that, and it was only when his wife passed away that he was able to explore that. So now he’s in the position of never having had a long-term male-male relationship. And whether or not he’s interested in having one—he says he’s not, he says he only interested in having more casual relationships—yeah, that’s definitely a product of his situation.

PJR: Yeah, absolutely, and you have to keep in mind that I’m looking at a particular group of LGBT seniors. And what I mean by that is they’ve lived through a very particular time in history. So Ty’s a great example, where he says many of the people who he grew up with who he thought he would grow old together with, you know, they died during the HIV/AIDS crisis. So that was a huge change in terms of who his community was. You look at someone like Dennis and he, you know, “played the game” and remained closeted and just tried to maintain a life as a heterosexual man and got married. And he says it in the film and he’ll tell you himself that he very much loved his wife and he very much appreciated that relationship, but he recognizes that he’s always had tendencies outside of that, and it was only when his wife passed away that he was able to explore that. So now he’s in the position of never having had a long-term male-male relationship. And whether or not he’s interested in having one—he says he’s not, he says he only interested in having more casual relationships—yeah, that’s definitely a product of his situation.

And then Robert, for instance, he found who he says is the love of his life, who he knows is the love of his life, and unfortunately he passed away, and I don’t think Robert’s interested in meeting anyone else, ‘cause he’s already met that person and it’s about moving on from that and accepting it for that time period that it was. And I think that is different from a lot of the heterosexual community, especially of people their age. So in that sense it’s unique to their experience, but I do think those issues of loneliness, partnership, self-acceptance and where you see yourself in a relationship, are universal.

H2N: In terms of creating a balance between reporting accurately and being true to your subject versus building a story, how do you approach that?

PJR: I always approach it from the perspective of what do I see as the difference between journalism and documentary film, which is that documentary is filmmaking, which ultimately is storytelling, and at least with the films that I’m making I’m not afraid to have a point of view and a perspective that is my own. And I’m not afraid that when someone watches it they will say, “Oh, that’s the way that PJ thought about it, and that’s the way he experienced it,” whereas I do feel the whole point of journalism is about having equal points of view and making sure you cover everything, and I think the difference between fiction and nonfiction filmmaking is that in nonfiction the events that are unfolding are true. They really happened in life, these are real people regardless of the film. But the principles of storytelling and the idea of interacting with audiences are similar to nonfiction filmmaking in that you can have a protagonist; maybe you can have three of them. You do want your audiences to connect with it. You do want them to feel certain emotions, the way a fiction film would also script out; the difference is that this is happening in real life. And I think that’s why I’m interested in nonfiction filmmaking. To me what’s even more powerful is knowing that it’s real. It’s not like someone came up with this, it’s not that I was sitting in a coffee shop calculating this. There’s some things you just can’t make up. I do think of course there’s a certain amount of trust that the audience is going to give you in terms of what you’re giving them is truthful, it’s not completely fabricated. And what’s funny is you see a lot of nonfiction films where the directors will also credit themselves as a writer, and I definitely have friends in the film world and not in the film world who look at that title and say, “Why do they have a writer title?” And it’s like, you know, you have to imagine: you have hundreds of hours and you pare it down—there is a certain amount of writing there, there is a certain amount of structure that has to come with that, awareness of storytelling, being aware of how something is gonna flow, and a lot of times that does come along with what we consider a writer.

PJR: I always approach it from the perspective of what do I see as the difference between journalism and documentary film, which is that documentary is filmmaking, which ultimately is storytelling, and at least with the films that I’m making I’m not afraid to have a point of view and a perspective that is my own. And I’m not afraid that when someone watches it they will say, “Oh, that’s the way that PJ thought about it, and that’s the way he experienced it,” whereas I do feel the whole point of journalism is about having equal points of view and making sure you cover everything, and I think the difference between fiction and nonfiction filmmaking is that in nonfiction the events that are unfolding are true. They really happened in life, these are real people regardless of the film. But the principles of storytelling and the idea of interacting with audiences are similar to nonfiction filmmaking in that you can have a protagonist; maybe you can have three of them. You do want your audiences to connect with it. You do want them to feel certain emotions, the way a fiction film would also script out; the difference is that this is happening in real life. And I think that’s why I’m interested in nonfiction filmmaking. To me what’s even more powerful is knowing that it’s real. It’s not like someone came up with this, it’s not that I was sitting in a coffee shop calculating this. There’s some things you just can’t make up. I do think of course there’s a certain amount of trust that the audience is going to give you in terms of what you’re giving them is truthful, it’s not completely fabricated. And what’s funny is you see a lot of nonfiction films where the directors will also credit themselves as a writer, and I definitely have friends in the film world and not in the film world who look at that title and say, “Why do they have a writer title?” And it’s like, you know, you have to imagine: you have hundreds of hours and you pare it down—there is a certain amount of writing there, there is a certain amount of structure that has to come with that, awareness of storytelling, being aware of how something is gonna flow, and a lot of times that does come along with what we consider a writer.

H2N: Were there any particular challenges in terms of figuring out how to tell a story in this particular film?

PJR: Yeah definitely, I mean I think when I approached each of the subjects of the film I did it in a different way, because they are such different personalities and the ways they interact with people are very different. For instance, Dennis is very much the silent adventurer, so there’s a lot of me—when I’m filming Dennis—recognizing that I shouldn’t intervene too much, I shouldn’t ask a lot of questions, I should just let it unfold, and be comfortable with that silence and see where it leads. Just because he’s quiet doesn’t mean he’s not thinking about something, or motivated to do something. And with Ty, he’s interesting because he’s so much more sociable as a person and he really is much more extroverted than someone like Dennis. I discovered that seeing him interact with a lot of people was a really great way to see who Ty really was, because it changes. The way he interacts with Stanton his partner for instance is very different from when he’s out on the street tabling for his organization. And then Robert, he’s someone who’s very intriguing because Robert, as much as he talks about himself, he doesn’t really talk about himself. You know, he definitely has his zingers, and he’s got the stories, but he’ll never talk about himself from the point of view of does he think what he’s done is important or what has he done for the community. And I discovered I really needed to ask other people. Namely his close group of friends that he considers family. Like Dixie, the head bartender: she will tell you about Robert’s personality and how generous a person he is, but Robert will never say that himself.

PJR: Yeah definitely, I mean I think when I approached each of the subjects of the film I did it in a different way, because they are such different personalities and the ways they interact with people are very different. For instance, Dennis is very much the silent adventurer, so there’s a lot of me—when I’m filming Dennis—recognizing that I shouldn’t intervene too much, I shouldn’t ask a lot of questions, I should just let it unfold, and be comfortable with that silence and see where it leads. Just because he’s quiet doesn’t mean he’s not thinking about something, or motivated to do something. And with Ty, he’s interesting because he’s so much more sociable as a person and he really is much more extroverted than someone like Dennis. I discovered that seeing him interact with a lot of people was a really great way to see who Ty really was, because it changes. The way he interacts with Stanton his partner for instance is very different from when he’s out on the street tabling for his organization. And then Robert, he’s someone who’s very intriguing because Robert, as much as he talks about himself, he doesn’t really talk about himself. You know, he definitely has his zingers, and he’s got the stories, but he’ll never talk about himself from the point of view of does he think what he’s done is important or what has he done for the community. And I discovered I really needed to ask other people. Namely his close group of friends that he considers family. Like Dixie, the head bartender: she will tell you about Robert’s personality and how generous a person he is, but Robert will never say that himself.

H2N: Was there anything that you found in the editing process that helped you to tell the stories?

PJR: Editing in general is a huge challenge, just because that’s where so much of the storytelling gets formulated. You’re at the point of “this is what I captured; how do I best present it?” There’s a certain detachment that has to happen in terms of like “Okay, I have to recognize that I think everything is amazing, but there has to be stuff that’s absolutely amazing.” And for me it was only possible because I had an amazing editor, Kyle Henry, who’s an amazing filmmaker on his own. For the most part I think just getting the initial assembly, paring it down to “Okay, this is what I think the essence of my film is,” is for sure the most challenging aspect. And this is me coming from more of a production background—I think that’s something I love about production, that you don’t have time to come up with multiple versions; it’s happening, so either you captured it or you didn’t. Either you were fast enough to think on your feet or you weren’t. And in a process like editing, I mean you could do that forever and ever and ever. At some point that commitment of making a decision just has to happen.

There were definitely challenges with each of the stories; like Dennis, for instance, even though he is quiet and he has his ups and his downs, and some of his downs are really big in the film, I don’t consider him tragic. I consider him actually hopeful. He’s someone who manages to navigate through life and find a way and search, and he doesn’t give up, and I think trying to convey that is really hard to do, because you don’t want the audience to just feel sorry for him. You want them to root for him to keep trying to find what he deserves to have. If you don’t get those moments where they push beyond that then it might just come across as a one-note thing. People are so complex and people’s stories and histories are so complex that you have to capture that complexity and it has to be reflected also in the edit.

H2N: What about the characters playing to the camera—I definitely got a sense of that with Ty and that amazing exchange he has with Stanton, where he keeps repeating, “It’s almost like I’m getting married.”

PJR: Yeah and he breaks the fourth wall by looking at the camera. I love that too—it’s a moment that reminds me of something like The Office. It’s the power of “come on people, you’re with me, right?” Early on, it was a challenge. I think a lot of it has to do with, you know, they’re from a different generation where they’re not used to cameras being everywhere. They’re not the type of people who are pulling out their cell phones, filming something and immediately posting it to YouTube. When they see a camera, there’s a lot more attention drawn to it in a different way. I think the only way to get around that intimidation of the camera is to earn the trust of your subjects. And that’s the thing, is they’ll be truthful and vulnerable in front of you, and the camera just happens to be there.

PJR: Yeah and he breaks the fourth wall by looking at the camera. I love that too—it’s a moment that reminds me of something like The Office. It’s the power of “come on people, you’re with me, right?” Early on, it was a challenge. I think a lot of it has to do with, you know, they’re from a different generation where they’re not used to cameras being everywhere. They’re not the type of people who are pulling out their cell phones, filming something and immediately posting it to YouTube. When they see a camera, there’s a lot more attention drawn to it in a different way. I think the only way to get around that intimidation of the camera is to earn the trust of your subjects. And that’s the thing, is they’ll be truthful and vulnerable in front of you, and the camera just happens to be there.

H2N: A lot of the work you’ve done has been with what you’d call queer content and I wonder if you’ve thought about what your specific areas of interest are within queer film or where you see yourself in that context.

PJR: I’m gonna talk about it in almost two different ways because there’s a way to think about it in terms of the actual representation, like is it a queer character? If you have a trans person for instance or an LGBT person in your film most people are gonna consider that a queer [film]. But I think there’s also this idea of is it a queer story? Is the content itself, just the subject, queer? And you do have these amazing queer directors, like I don’t think Bruce LaBruce will ever make anything that’s not queer, regardless of the content. He could make his version of a mainstream romantic comedy and for sure it’s gonna be as queer as hell. And I think so much has to do with just who he is.

H2N: I mean you could say that about, like, George Cukor too.

PJR: Exactly, so I think that’s kinda how I’m starting to think about my own work, like I’m not setting out and saying, “Okay, what’s the next queer film I have to make?” For me it’s just what’s the next subject matter that I wanna tackle or the next story I’m interested in telling. And I’m sure there’s gonna be some kind of queer aspect to it. But I do hope that people understand that it shouldn’t be excluding people too. Because a lot of these concepts of what we consider queer, if you really break it open, it really does encompass a lot of things, like outsider stories. It encompasses more experimental or more unidentifiable, or even films that don’t even have a genre term yet. A lot of things could be considered queer in that sense, because it’s groundbreaking right? I would love to extend the term queer in terms of thinking like you’re not catering to what’s the norm. So part of that is just really allowing yourself to be creative and uninhibited and unapologetic with what you’re doing. And I think that the queer filmmakers that you do see in Hollywood are doing that. People like Todd Haynes. Almodovar. Almodovar is I think one of the most amazing filmmakers because he’s able to create a narrative with these characters that—anyone’s gonna say these characters are crazy, queer, whatever, but they’re so emotionally grounded and you’re so into their stories he—in a way, there’s so much power behind that in terms of saying it’s not about their identity, it’s about their experience, right? And we’ve all had something we can relate to that way. There’s something amazing about that kind of filmmaking. But meanwhile, you have someone like Travis Matthews, you have all these newer queer filmmakers that are making films that are doing the film festival circuit right now that are creating this amazing new work. Like Interior. Leather Bar., people are talking about that and it being something people haven’t seen before.

H2N: So as the LGBT community is being to some extent assimilated, at least in certain parts of the western world—I mean, traditionally queer identity has been so wrapped up in being an outsider with a history of oppression—do you think that could fundamentally change the idea of what queer or gay or lesbian culture is?

PJR: I think just by saying you’re queer or identifying as someone in the LGBTQIA community, there’s a certain amount of challenges that are always gonna come with that. Because it’s not the norm. And I think because of that there’s always going to be a fraction of people who are gonna be aware of that challenge and embrace that challenge and go with that challenge and won’t wanna be categorized in the same way, they won’t wanna be heteronormative and they won’t wanna feel like they have to subscribe to the same things that the heterosexual community does, and I think there’s definitely a place for that, and I hope that is something that never goes away because that is something that keeps us always moving forward and questioning things. There always has to be that aspect of a community that somebody’s questioning why things are happening that way. And challenging it, and coming up with alternate ways, alternate ideas and different points of view. And I think that’s what makes the community a lot more rich. You have for instance like DOMA being struck down and the concepts of gay marriage—there’s always gonna be a fraction of the LGBT community who is against same-sex marriage because they don’t wanna feel like the LGBT community has to be part of something that they consider heteronormative. I definitely have friends who are like, “Oh my God if I see a gay marriage I’m just gonna shoot myself.”

PJR: I think just by saying you’re queer or identifying as someone in the LGBTQIA community, there’s a certain amount of challenges that are always gonna come with that. Because it’s not the norm. And I think because of that there’s always going to be a fraction of people who are gonna be aware of that challenge and embrace that challenge and go with that challenge and won’t wanna be categorized in the same way, they won’t wanna be heteronormative and they won’t wanna feel like they have to subscribe to the same things that the heterosexual community does, and I think there’s definitely a place for that, and I hope that is something that never goes away because that is something that keeps us always moving forward and questioning things. There always has to be that aspect of a community that somebody’s questioning why things are happening that way. And challenging it, and coming up with alternate ways, alternate ideas and different points of view. And I think that’s what makes the community a lot more rich. You have for instance like DOMA being struck down and the concepts of gay marriage—there’s always gonna be a fraction of the LGBT community who is against same-sex marriage because they don’t wanna feel like the LGBT community has to be part of something that they consider heteronormative. I definitely have friends who are like, “Oh my God if I see a gay marriage I’m just gonna shoot myself.”

So do I think that it will ever be completely mainstream? No, I think definitely the perception might, and I think that’s where it gets dangerous because you might see a gay teen character on television—that doesn’t mean there’s not a kid somewhere in the United States who’s still getting bullied and dealing with homophobia. It just means there’s definitely more visibility or acceptance of it on television, which is great, that definitely is a start. Making this film, and dealing with seniors—again, there’s a lot of emphasis placed on the youth community and there needs to be, they’re definitely a vulnerable group, but at the same time we need to have that same thing for someone who’s 80. Who’s to say that someone at 80 is not going to one day say, like, “OK it’s time, whatever has happened in my lifetime has led to right now, to me deciding to come out; how am I gonna do this?” And we need to make sure that they have a support system.

H2N: When I interviewed your collaborators Kyle Henry and Paul Soileau last year I had written a list of questions and one of them was “Are you political?” But by the time we got to that question it was like a joke. Your position seems to be more like, “Aren’t all these different points of view interesting,” and I wonder if you see your work as political in that sense or maybe in a different sense.

PJR: It’s interesting because the other day during one of the Q&As someone said, “As a filmmaker and an activist,” and I said, “Activist?! I don’t think I’ve ever considered myself an activist.” And they were like, “Well, clearly you’re making work that’s like raising issues, so there’s some kind of activism going on…” [Raval laughs] And I said, “Well, it’s true. But I would like to think that the kind of work I’m making doesn’t put the issues at the forefront. I would like to think that I’m making the kind of work, at least with the documentary work that I’m doing, that’s about people, and you get to experience their lives and the challenges and the issues that they deal with come through—just their daily existence. And that’s where you get to experience it. I try to avoid as much as possible just telling you a fact. I don’t want you to think about the abstract numbers and statistics; I want you to see an example of someone who is in that statistic. And if it makes you think about something differently, if it motivates you to try to change your community or society in a certain way then so be it. But I’m not trying to make work where my intention is for everyone to run to the polls and vote a certain way.

That’s what’s so amazing about nonfiction film: you get to sit in someone else’s life for an hour, maybe two hours, and in that process get to see what someone else experiences. And maybe that whole idea of being in someone else’s shoes makes you think of something you’ve never even thought of before. And I think a lot more of that needs to happen, because that is a huge problem with society at large. There’s a lot of, “Well you’re there and I’m here and we don’t need to understand each other because we have nothing in common.” Well we actually do. Because we’re gonna either walk down the same street, or I’m gonna stand in line right next to you. We should be aware of each other, we should understand where we’re coming from, and what does connect us. I can be some kind of radical queer or whatever, and someone could be some older, Republican, white heterosexual… senator! And we could equally experience heartbreak. We could equally experience loss. We could equally experience the idea of rejection and the desire for self-acceptance. So I think a lot of the filmmaking that I’m interested in looks at that. The human condition is that you experience and you feel and in that process you become the person that you are. And I’m gonna become one person and someone’s gonna become another one but we’re also gonna have similarities in terms of the significant moments of our lives. And I hope that’s what Before You Know It does for some people. That they get to experience what these three gay seniors are experiencing and connect with them.

— Paul Sbrizzi