A Conversation With Miguel Gomes (ARABIAN NIGHTS)

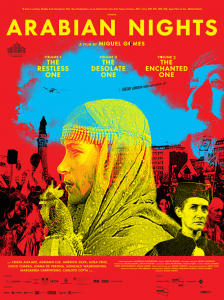

The Portuguese director Miguel Gomes became a name to watch among cinephiles when Tabu, his beautiful, black and white fantasia on the Portuguese colonial system, shook up the 2012 Berlin Film Festival. His follow-up, Arabian Nights, is an epic, three volume series of contemporary Portuguese tales told through the framework of the classic, extemporaneous stories spun by Scheherazade in the literary classic of the same name. Hammer To Nail sat down with Miguel Gomes at the 2015 New York Film Festival, where the films made their U.S. debut, to discuss this epic work and its social and political reverberations. Arabian Nights: Volume I- The Restless One opens Friday, December 4th at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, with the remaining volumes opening soon after and across the country.

The Portuguese director Miguel Gomes became a name to watch among cinephiles when Tabu, his beautiful, black and white fantasia on the Portuguese colonial system, shook up the 2012 Berlin Film Festival. His follow-up, Arabian Nights, is an epic, three volume series of contemporary Portuguese tales told through the framework of the classic, extemporaneous stories spun by Scheherazade in the literary classic of the same name. Hammer To Nail sat down with Miguel Gomes at the 2015 New York Film Festival, where the films made their U.S. debut, to discuss this epic work and its social and political reverberations. Arabian Nights: Volume I- The Restless One opens Friday, December 4th at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, with the remaining volumes opening soon after and across the country.

Hammer To Nail: Let’s begin by talking about your initial discovery of the original text of Arabian Nights. How did you encounter that book?

Miguel Gomes: I took it from the shelf when I was 12 or so, in my father’s house, and I never finished the book. It’s a big book, with lots of volumes, but every year, I went back to read some more. Since the beginning, I was completely amazed and attracted by the structure, which gives you vertigo almost; stories within stories, changing all the time, the writer changing all the time and these tales are shifting all the time. In the case of these films, there is not a single tale— there are sentences, maybe a character. But what I really took from the book was my impression of reading of reading the book, the sensation I had diving into this book and being completely amazed by this endless labyrinth of tales.

H2N: What challenge did that present for you as a writer, working on the structure of the movie, and how did you adapt that situation to dealing with the conditions in Portugal today?

MG: I see a parallel between the stories that were happening in that moment in Portuguese society, they had this sort of surreal, wild dimension because when you have a socioeconomic crisis, everything goes more extreme, more wild, more chaotic. And I saw the connection between this and the book, which is itself pretty much rock-and-roll. So, I thought “Let’s summon the queen of wild fiction, the rock and roll queen before there was rock and roll, to help me tell the story.” When I was thinking of making a film called Arabian Nights I knew I had a challenge because you can’t reference that book and then make a simple, horizontal line of storytelling. So, I knew that the richness of the film should be in its diversity. It’s not very rational, but I always have the sensation when I finish a film that the new film reacts to my previous film. So, for instance, Tabu is a much more elegant film, so I knew I wanted to make a wild film as a reaction against that, to put myself in a mode of production where I had less control, to discover the film while I was making the film, not have the script and then shoot, but instead, I got the camera and crew, and I decided to make a “live” fiction, to react to events by being able to create fiction.

H2N: Do you see a relationship between that type of filmmaking and films that have a specific political point, maybe the so-called “revolutionary cinema” of the late 1960’s? This film feels rooted in the values of the working class, but what is your position as a filmmaker? You seem to be a collector of stories, but how do you relate to these stories?

MG: I guess in different ways because every segment is so different, you cannot have the same type of connection between, say, the politicians and the bankers; I’m not close to their point of view and I think it is very hard to get to them — I didn’t try, but I imagine it is difficult. So, in that segment, it follows the codes of the farce and the popular satirical tradition. But in the last segment of the same volume (Volume I) called The Magnificent, the accessibility of the working people allows me to be much more direct. I can work in a different way. So, all of the characters we have on the film and all of the cinematographic approaches we have, it depends on my proximity to the characters and the real people.

H2N: Did you find any of the segments more meaningful for you personally?

MG: Yeah, but I don’t know if that is important for me. In this case the idea was to have an unstable progression, but also, to have a much wider range, not to be so precise, not to be so close to a subject I may enjoy personally. For instance, I think I am very happy with the Tears Of The Judge segment, the trial. But other stories, maybe they are more weak, but the range is what is important, allowing you to go in directions where things are not so solid. The weakness of those segments can also be touching for me personally and what interested me was to go from one to the other and have all of these ways to show the world and approach people, being different in each moment.

H2N: How did the structure of each segment reveal itself to you. They’re all different, the Judge sequence is very theatrical, you have the documentary style of the bird group, in another you have this Baghdad, which is not Baghdad at all — all very different. How did you choose which approach was for which story?

MG: There was not a general strategy, we were reacting to what we had in each moment and my desires were always changing. You mentioned the bird part, and for me, it was like doing a documentary, but I was documenting this surreal fiction because these guys with computers trying to teach birds to sing the way they wanted them to sing, this seemed so unreal, but at the same time, you’re right, I just entered their homes with my camera and looked at what was fascinating to me. I think that segment for me has the perfect balance between reality, telling the stories of the proletarian class in Lisbon, but also documenting a completely bizarre activity I had no idea existed, and me just turning on the camera and them doing what they are doing. I love the contrast between these little animals and these tough guys — if you shot this in New York, they’d be mafia guys. You see guys who should be in a Scorsese film discuss how birds should be singing, so it was both surreal and very real.

Also, in another segment, you mentioned there is this Baghdad, which is a completely fake Baghdad. I had the feeling I was filming mythology, Scheherazade and her Baghdad, and bringing it back down to earth. So it was also this contrast of bringing the mythological down to earth here, and in the other segment, creating mythology out of very ordinary kind of guys, out of everyday life. It created a lot of options for mise-en-scene, but I responded in a very intuitive way. I can only discuss this with the distance of hindsight; months have passed since I made this, and now I can see what I was doing. When i was doing it, it was more of an urge to shoot, a fascination, not a rational approach. So, when I am editing and then talking about the film afterward, that’s when I start to put things in order. When I’m making it, I have to follow my intuition.

H2N: There is also a thread running through the film of the dynamic of power and the way people respond to it. You have the Judge sequence, you have the bankers and politicians, you have the cockerel on trial, and people trying to get justice. What makes the Judge sequence so effective for me is you show the interrelated nature of the system, that it is not a single act or decision, but a chain reaction.

MG: In a general way, what I think after making this film, is that I try to express the value of individuality, making characters that are sometimes eccentric, unusual or obsessed, and the collective. The best example is the guy in the first segment from the union; he is completely obsessed by something that seems strange – he wants everyone to reform a ritual. Normally, you don’t have union guys who want to do this type of thing, so his own obsession turns into a community ritual. I think this film is always working between intimate things and the public, collective dimension. There is an issue as to how the collective can save themselves, can deal with power. In the case of the Judge, its that everything is a little bit lost, this idea of a sense of place and belonging is lost, and the one who should be regulating things and making order, the tools are not able to handle the situation, which becomes hopeless. I call this volume The Desolate One but I could call it The Helpless One because I think all of the characters are helpless. This is why they think about the dog like a messianic figure who brings happiness, because they live in misery and can’t fix it.

H2N: Speaking of which, you give agency to the animals in this movie. I’m wondering if that is a way of connecting this idea of “earth-bound” to the characters.

MG: Yes, and this also comes from The Arabian Nights, I took it from the book, but you also have the contrary examples. You have the cow and cockerel who have this wisdom, but the tragedy is that no one listens to them because they can’t understand them, but the opposite is Dixie, who is just a dog like in a Walt Disney film, he’s just appearing in the wrong country and in the wrong film.

H2N: This films speaks to Portugal specifically, but these situations and this crisis also has had a huge impact on Europe as a whole, but even Spain, Greece specifically. Did the idea of a European crisis factor in for you?

MG: Portugal was not alone in what happened. What was common among all of these countries in Europe was the money stopped flowing, and the response was one about Western civilization and its true values of democracy and ideas outside of the realms of trade and business. Suddenly, those democratic ideas don’t seem so solid. Look at the recent refugee crisis and you can see how difficult it is for European countries to communicate with one another. When I was casting The Magnificent segment, those people are unemployed. I did over 100 interviews with people, and their stories were hard to hear, and I would arrive home and hear the Prime Minister of Portugal and I had the sensation that these two ways of speaking were opposite of one another. One was about all of these layers of statistics, which for me was the fictional one, and it was bad fiction because I felt he was lying. He was trying to describe reality in a way that benefitted himself. So, I said, “let’s fight back with real fiction,” and the power of fiction is what I can do as a filmmaker to confront the bad fiction, the lying, the pretending things are ok when they are not.

H2N: As in, you’re a filmmaker in that situation. You don’t buy some paint and make a painting, or sit alone and write a book, you make films, it is collaborative, you have a crew, you’re spending other people’s money, it’s not cheap and easy. How did the economics affect the film?

MG: Yeah, people who give money to me, if they want me to work with them, they understand from the start that I will do my stuff. They give me carte blanche. For instance, to get co-production money from institutions and other countries, we didn’t have a script. It was impossible; we were going to write stories from Scheherazade, but brought into the future. So what we showed them was a model of how to produce the film, almost like a manual of our process. It was the process that was sold, and it’s a big risk because with this production model, there’s a chance I could do a very bad film; anything is possible. But I think people were interested in us reacting almost live to real events and trying to create fiction, and I thought even if there is anger or sadness as to what is happening in the world, it’s my job to make a film that is not a personal vendetta or something. Cinema is not a judge. Even when we have negative characters, they aren’t the devil. They are naive, like children, and that is a side we can like. My intention is not propaganda. You mentioned the militant films of the 1960’s, the problem with them for me is that they focus too much on where to go. And me? I don’t have the answers for saving the world, I’m not capable. That doesn’t bother me though, because I see all the politicians, and they don’t have an answer either.

H2N: I wanted to ask about the look of the movie. The segments all have very different looks and I understand you signed up your DP without him really knowing what it was you planned to do.

MG: He had no idea. (laughs) I think when you are working together, you have certain decisions, say making a radical choice like shooting on black and white stock — you make a choice and you go into black and white mode. You prep for that, the way you place the camera, the way the characters are detached from the background, everything is different because it’s another way to see the world. In this case, I wanted to be a little more heterogeneous, but we had an idea to use the whole screen, anamorphic lenses, but let’s do it in 16mm so that, when you blow it up, the grain gets even bigger with less definition. So, you’re using a rich format with poorer material. And that’s the movie, too, the epic tradition in the low. We decided to use 35mm only on the Scheherazade sequence because she’s a rich girl, a character from Sofia Coppola! We even thought about shooting her in 70mm, taking this idea to its logical conclusion, but the math didn’t work out for the budget.

H2N: Throughout the movie, there are several rhymes throughout both the three film structure, but also the films within each stand alone film. Can you talk about building that in the editing room?

MG: During the sixteen weeks of shooting over 14 months, during the first half of that period, it was impossible to think about these things because it was the beginning. But in the second half, we knew what we already had, and it became easier to start thinking about how these things rhymed, to make connections. But I would say most of them are due to me naturally being obsessed with certain themes and I would just go back to them. For instance, the idea of animals in the film as they do in fables. Editing allows you to see much more, and in this case it was difficult because there is so much material. In this case, it was the first time I worked with more than one editor, with the second editor assembling things while we were working. So, he made the first version of the film as we shot, and we would come to him, hearing new ideas, which became very important. After we finished, we set up two rooms and I went back and forth between the two rooms as we worked on different parts of the film, and then in the end, we added a screenwriter to do the voiceovers while we were editing.

H2N: You mentioned the “rock and roll queen” and I had the notion watching this that assembling the final film must have been a little bit like sequencing a rock album, in this case, a triple album. Did that come to mind for you, a sort of sequencing idea?

MG: Funny, there was a guy in Portugal who said it was like The Clash’s Sandinista and I had never thought about it before. I would say the rock and roll was in the spirit of Scheherazade and the times we were living in Portugal, inspired me to improvise more than I ever have, and really to try to react and give whatever I had to what was happening. So, it was more like a rock and roll concert than an opera. It was more blue collar, more Bruce Springsteen.

H2N: Final question about the actors. You give big roles to non-professionals, little roles to established actors. Can you talk about casting the film?

MG: Yeah, it came down to the multiplicity of elements I wanted this film to have. There had to be space for professional human actors, a professional dog actor — he won the Palme Dog! One of the biggest actors in Portugal is the one who plays the union guy, and he’s playing with real unemployed people, and if the actor is good, he will do what it takes to get a good performance out of his non-professional counterpart. I knew that the range of the film would include the pleasure of both a highly theatrical performance, like that of the Judge, moments that feel fictional and other moments that are really what takes place in the world with real people. To give voice to them.

H2N: Thank you, Miguel.

MG: Thank you.

— Tom Hall (@BRM)