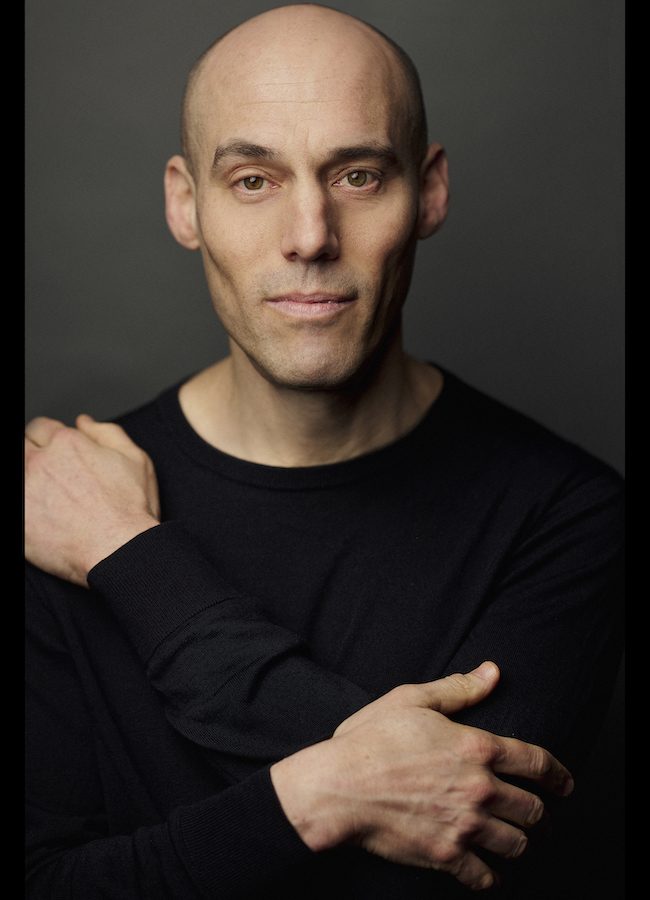

A Conversation With Matthew Ross (FRANK & LOLA)

Matthew Ross’s noir-tinged drama Frank & Lola world premiered at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival, where it was picked up for distribution by Universal Pictures. Starring Michael Shannon, Imogen Poots, Emmanuelle Devos, Michael Nyqvist, and Justin Long, Frank & Lola is an intense exploration of the more insidious feelings that love can inspire: jealousy, pain, betrayal, and that’s just for starters. On the eve of the film’s theatrical and VOD release on December 9th, I spoke with Ross in order to focus on the epically long path it took to get him to turn his feature-length directorial debut into a reality. (Visit the film’s official website to learn more.)

Matthew Ross’s noir-tinged drama Frank & Lola world premiered at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival, where it was picked up for distribution by Universal Pictures. Starring Michael Shannon, Imogen Poots, Emmanuelle Devos, Michael Nyqvist, and Justin Long, Frank & Lola is an intense exploration of the more insidious feelings that love can inspire: jealousy, pain, betrayal, and that’s just for starters. On the eve of the film’s theatrical and VOD release on December 9th, I spoke with Ross in order to focus on the epically long path it took to get him to turn his feature-length directorial debut into a reality. (Visit the film’s official website to learn more.)

Hammer to Nail: I’m currently in a place where it feels like I’m never going to make another movie again. I know how incredibly long the journey has been for you to get to this point so let’s talk about that as it might provide a glimmer of hope to me and other people who are feeling that same pain! I can’t even remember now but how long ago was it when I first read the script?

Matthew Ross: You blogged about my script in 2006.

H2N: So ten years ago. Wow.

MR: That’s ten years ago. We made the film two years ago. At that point, when you had first blogged about it, I was about to quit my job at Filmmaker Magazine to go direct Frank & Lola, and that’s what I did in the fall of 2006. And we did not get into production until the fall of 2014. Throughout those eight years, I would say probably seven years total at least, we had at least one major element attached to the movie, whether it be an actor, two actors, some of the money, all of the money, all of the money and one actor but not the other one. So I was trying to get this film made in a real way with real professional people behind me and it was madness, to say the least. I was prepared for a difficult road—I mean, I’d been a film journalist before that and I knew tons of stories—but I wasn’t prepared for it to take this long. Every conceivable thing that could go wrong happened. You know, making a film is like trying to gather ants with a spoon. Say you need five pieces. You have one, two, and then right as you get three, one falls apart. Then you get one back and two goes, but then you get four. So you’re chasing this carrot that’s right in front of your nose.

I don’t come from a background where I’m independently wealthy. I have to figure out how to support myself while doing this and having the flexibility to go to LA or New York, depending on where I was living at the time, to meet with a financier or meet with an actor, and pay for that trip out of my own pocket most of the time. And so that would entail basically not ever taking a full-time job. Or turning down big work opportunities on occasion because I was assured by several well-intentioned people that my movie was going into prep in three months, only to have the thing fall apart, and then have the job disappear, and then be stuck and broke without a movie going into production.

I don’t come from a background where I’m independently wealthy. I have to figure out how to support myself while doing this and having the flexibility to go to LA or New York, depending on where I was living at the time, to meet with a financier or meet with an actor, and pay for that trip out of my own pocket most of the time. And so that would entail basically not ever taking a full-time job. Or turning down big work opportunities on occasion because I was assured by several well-intentioned people that my movie was going into prep in three months, only to have the thing fall apart, and then have the job disappear, and then be stuck and broke without a movie going into production.

H2N: Yep.

MR: Mike, you’ve been there, man, you know it. It challenged me in every conceivable way, and in ways that don’t just affect your professional life. You know, personal relationships, emotional and psychological health, all of those things get challenged along the way. At some point, almost right before we actually made the movie, even my most ardent supporters and people who cared about me very much and had supported my doggedness throughout this whole process, had begun to be like, “You know, man, maybe you should just take a break from this and come back to it later and do something else,” because they saw what it was doing to me.

H2N: Last year when I talked to John Magary about The Mend he said something great about how sociopaths make the best directors. [MR laughs] Or if that’s too extreme, there really has to be some semblance of delusion or I-don’t-know-what to keep a person going through all of the rejection and signs that are pointed so directly against you. It’s just so incredibly hard if you’re a somewhat normal and sensitive human being to not give up.

H2N: Last year when I talked to John Magary about The Mend he said something great about how sociopaths make the best directors. [MR laughs] Or if that’s too extreme, there really has to be some semblance of delusion or I-don’t-know-what to keep a person going through all of the rejection and signs that are pointed so directly against you. It’s just so incredibly hard if you’re a somewhat normal and sensitive human being to not give up.

MR: I remember at one point, I think maybe about a year before we finally did it, one of my producers called me up and said, I remember the phrase they used because it stuck with me, “There seems to be a sense among the producers that you have a delusional confidence in the ability of this film to get made.” [H2N laughs] “Delusional confidence.”

H2N: Well, shit, it did eventually get made so there ya go! If you didn’t have some kind of abnormal driving force then you’d have checked out in like 2009 and been like, “Forget it.”

MR: Did I tell you that all of our money fell apart two weeks before hard prep was about to begin and after I’d moved out of my New York apartment and was living on my assistant’s air mattress in downtown Vegas? And we ended up getting the money with an hour to spare? We had two weeks to get it and we got it at Friday 5pm Pacific time. Had we not gotten it by six the entire thing would have fallen apart.

H2N: I mean…

MR: It was kind of the perfect ending to this struggle. At the very end it really looked like… our chances of succeeding those last two weeks were really tiny. And then all of a sudden we finally got that crazy stroke of luck that I’d been waiting on for eight years.

MR: It was kind of the perfect ending to this struggle. At the very end it really looked like… our chances of succeeding those last two weeks were really tiny. And then all of a sudden we finally got that crazy stroke of luck that I’d been waiting on for eight years.

The other thing you learn is you can be as talented as Stanley Kubrick and as hardworking as Barack Obama and it still is not gonna work out unless you have a big stroke of luck. You can treat everybody really well, and I think I did along the way. I just needed a happy accident to happen and that’s what ended up happening. But you also have to be able to stick in the room long enough for that to happen and that’s what I did.

H2N: I know you did lots of other stuff these past ten years, like the boxing shorts for example, but when it came to feature filmmaking were all your eggs in this one basket?

MR: In terms of directing, this was it. There were certainly other projects I considered along the way. I wrote a couple of original specs. But this was always front and center. Also, because we had producers for it and we always had some money and actors, so it wasn’t something I shouldn’t have been focusing on because it was supposed to be happening! And you know I directed this web series on professional fighters, I did a ton of rewriting in Hollywood along the way on various projects, I did some investigative journalism for Playboy, I continued to do freelance film journalism. Whatever was paying the bills, really. Whatever I need to do to continue to try to make Frank & Lola is what I did.

H2N: Removing that last-minute panic of the film falling through, at what point did you feel like it was actually going to happen that time, like what got you to actually give up your digs in NYC and head to Vegas? When did you think, “Okay, now we’re in the clear, this is really happening.”

H2N: Removing that last-minute panic of the film falling through, at what point did you feel like it was actually going to happen that time, like what got you to actually give up your digs in NYC and head to Vegas? When did you think, “Okay, now we’re in the clear, this is really happening.”

MR: To be honest, I didn’t really think it was happening until our department heads began to arrive in Las Vegas. That’s when I knew that it was happening. Up until then I wasn’t sure. And then when we got into prep, I just dove right in. It was so nice to not have that anxiety anymore.

H2N: At what point did you attach these particular actors to the project?

MR: Well, Mike was attached in 2009. He was attached for two years, then we got the money, and then the next day—not exaggerating—we lost him to Man of Steel. That’s kind of a perfect little microcosm of what those eight years were like. [H2N laughs] So then, fast forward three years, we’ve got Imogen, we were talking with another actor, decided to move on from that situation, and then—this was pretty close to prep, like a month or two before going into prep—Michael’s name showed up on a list that CAA had sent over to us, because they represented Imogen. And I was like, “Is this actually for real?” I didn’t think there was any way we could get Michael at that point, because in the ensuing three years his career really took off. But they were like, “No, Mike’s always loved the script, he really liked you, he’s up for it.” And I think the main reason is because he’d never played a romantic lead before. When you’re somebody like Michael Shannon, who’s probably offered the lead in every single independent film that’s being made, you need a reason to take that pay cut and do it with a first-time director. And I think that was ultimately the final straw in securing him.

H2N: Did you get to rehearse with the actors beforehand or how did that play out?

H2N: Did you get to rehearse with the actors beforehand or how did that play out?

MR: Frank & Lola was the third film back-to-back-to-back that Imogen had made that year. She had just finished Green Room like two or three days earlier, I think. They’re both based in New York, and so I flew back to New York over the Thanksgiving holiday, and I sat down with them for two days in Red Hook, in a rented Airbnb apartment where they did fittings with our great costume designer Kammy Lennox, and then we did a read-through of the script in those two days. I flew back to Vegas, they showed up a few days later and then we were in production and that was it.

H2N: It’s so clear to me, and it is such an incredible asset, to know that we are actually in Vegas and France and you didn’t try to fake the locations. Is that something you had to fight for or was that something that was understood as you assembled your team, that you wouldn’t settle for a “fake it for the rebate” situation?

MR: That was brought up. It was certainly brought up that we’d do the Paris interiors somewhere else. But I just said there was no way. It needed to happen where it happened.

H2N: For every single reason it makes the finished product more successful, I’d venture to say always but definitely in this case. But it’s just become such a common part of the development conversation that it’s refreshing to hear that this wasn’t one of the bigger headaches you had to deal with along the way.

H2N: For every single reason it makes the finished product more successful, I’d venture to say always but definitely in this case. But it’s just become such a common part of the development conversation that it’s refreshing to hear that this wasn’t one of the bigger headaches you had to deal with along the way.

MR: No, and it was something I’m very happy I did because I’m really proud of the way the film looks and the production value and the overall authenticity.

H2N: How was working with a French crew?

MR: We had a great French crew, a great French production partner in these guys FullDawa, who are wonderful. But shooting in France is more challenging than shooting in the US for sure. A: The Paris traffic is absurd. And parking permits, the streets are old, they’re cobblestone. Just moving things around is a lot more difficult because it’s such a historic city. But there’s also the labor laws there. You have two hours less time every day to shoot, and you’re on French hours. So, for example, you show up at 7pm for a night shoot, and then at 8pm you have an hour-long lunch. [H2N laughs] And then you’re back in. So it’s more challenging. I have total respect for unions and, of course, all film crews, but put it this way: Of the stuff that you see in the film that’s in Paris, that’s basically all the coverage that we had. Whereas, you know, in Vegas we had tons of options for most scenes. In Paris, what you see is what you get. Cutting Paris was not very difficult because that was all the coverage we were able to get. [MR laughs]

MR: We had a great French crew, a great French production partner in these guys FullDawa, who are wonderful. But shooting in France is more challenging than shooting in the US for sure. A: The Paris traffic is absurd. And parking permits, the streets are old, they’re cobblestone. Just moving things around is a lot more difficult because it’s such a historic city. But there’s also the labor laws there. You have two hours less time every day to shoot, and you’re on French hours. So, for example, you show up at 7pm for a night shoot, and then at 8pm you have an hour-long lunch. [H2N laughs] And then you’re back in. So it’s more challenging. I have total respect for unions and, of course, all film crews, but put it this way: Of the stuff that you see in the film that’s in Paris, that’s basically all the coverage that we had. Whereas, you know, in Vegas we had tons of options for most scenes. In Paris, what you see is what you get. Cutting Paris was not very difficult because that was all the coverage we were able to get. [MR laughs]

H2N: Have you used the success of the film to hit the ground running on another feature? Or has it taken some time to process that this movie is now finally in your rear-view mirror after it was on the horizon for so long?

MR: I definitely hit the ground running. I think I’ve been out to LA five times since Sundance for marathon two-week trips. There’s a bunch of stuff in the works. I just sold a pilot. I’m not sure whether I can announce it yet but I can say that I sold a pilot, which is exciting.

H2N: Hell yeah!

MR: Thanks, man. Then there are a couple of bigger films that I’m working on right now, one of which may go very soon. Hopefully it will, but you know. I think it was Scorsese who said he doesn’t believe he’s made the film until he’s buying popcorn for it. If anything, I’ve learned not to count my chickens before they’re hatched, but I’m optimistic that the next film won’t take eight years to get made.

— Michael Tully