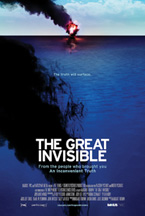

A Conversation With Margaret Brown (THE GREAT INVISIBLE)

(The Great Invisible is being distributed by RADiUS-TWC and opens theatrically on October 29, 2014. It world premiered at the 2014 SXSW Film Festival, where it won the Documentary Grand Jury Prize. Visit the film’s website to learn more.)

(The Great Invisible is being distributed by RADiUS-TWC and opens theatrically on October 29, 2014. It world premiered at the 2014 SXSW Film Festival, where it won the Documentary Grand Jury Prize. Visit the film’s website to learn more.)

Margaret Brown brings a unique feeling of intimacy to nonfiction filmmaking. From her debut feature Be Here To Love Me: A Film About Townes Van Zandt, which explored the famed singer songwriter’s life with a beautiful sense of longing and place completely in tune with its subject, to The Order Of Myths, which examined the history of race and class divisions through the smiling façade of Mobile, Alabama’s Mardi Gras celebrations, Brown has never shied away from telling a big, human story. In her new film The Great Invisible, Brown brings her unflinching eye to the Gulf Oil spill and the Deepwater Horizon disaster, and the results are predictably complex and moving. I sat down with Margaret Brown in Manhattan to discuss The Great Invisible and the challenges of tackling a story that may have fallen out of the national consciousness, but which remains a haunting call to arms for audiences.

Hammer To Nail: The Great Invisible seems like a transition or expansion of your previous work; it’s intimate, but in a different way than your other films. What inspired the change? It’s a huge story, obviously, so I assume you had to modify the approach?

Margaret Brown: I think I get bored, and I don’t want to do the same things over and over. I want to make a fictional narrative next. I’m not sure that I will, but I want to, and I’m open to whatever obsesses me as much as my last three films have. I also think this story is bigger, and I want to tell it that way. It started with me wanting to tell the story of what happened in this community when the cameras went away, and then it became this story a year and a half later about this apparatus under the Gulf Of Mexico that we’re all connected to. That’s a hard conversation to have with your funders, a year and a half in and you’re like, “I was interested in this, but now I think it’s a completely different movie.” That’s what happened. What I wanted to say changed.

H2N: The news cycle of this story, or stories in general right now, has become so compressed that things, not to make a pun, but they become invisible again. Did you feel a sense of responsibility about handling this story, making things relevant and immediate again?

MB: I think I wanted to show a portrait of the modern South, but through the lens of the oil spill. I wanted to show how these things in the South are so entrenched; it’s not as simple as “Boycott BP.” It’s not as simple as that. We’re all dependent on it, there’s no clear path to not being dependent on it for the near future. I mean, yes, there’s an activist film to be made there, but I wanted to focus on the people who are in that world. Beyond the talking points, what is that world, really?

MB: I think I wanted to show a portrait of the modern South, but through the lens of the oil spill. I wanted to show how these things in the South are so entrenched; it’s not as simple as “Boycott BP.” It’s not as simple as that. We’re all dependent on it, there’s no clear path to not being dependent on it for the near future. I mean, yes, there’s an activist film to be made there, but I wanted to focus on the people who are in that world. Beyond the talking points, what is that world, really?

H2N: All of your films have addressed a form of cultural entrenchment. There are so many layers to those stories, and here as well.

MB: I like the layers. I like the grey. I like it when it’s not obvious. I’ve worked with some people who want me to make things more obvious, and I’m so resistant to that.

H2N: So, The Order of Myths is a really personal film, and this one has that feeling as well, albeit in a different, maybe bigger, way. How do you incubate yourself into these worlds and earn the trust you need to tell these stories?

MB: With both films, the issue is access and time. I think one of the reasons I got the money for The Great Invisible was that I had just finished The Order of Myths, people knew I was in that community and I was able to say, “Look, you know I understand this community.” There’s a film about it. It’s not the same people, but I’ve already proven I can go in and get myself in there. After the spill, everyone was making a film about it—there must have been 20 oil spill films. But no one was from Alabama. Maybe since, but not when we started.

H2N: So what do you think about that idea? I heard a new phrase coming from those critical of political action in Ferguson, Missouri—people called it “social justice tourism.” But is there a real resistance to people coming from the outside, does it help someone like you can get more access?

MB: I think really good films can come out of people going somewhere totally foreign to them and making a movie. I don’t want to be one of these “essentialist” people—I don’t believe in that, either. I think if you’re of something, it makes it easier sometimes. There’s a shorthand. It doesn’t make you a better filmmaker, though. Maybe quicker? There’s a bar where we shot, it’s where a lot of the shrimp boats land, it’s the coolest bar ever. We would go there and they would say, “Oh, are you from New York?” just because I’m from Mobile, Alabama and not from there. That’s already a class difference, and there are assumptions about who you are. So, even though I can convince funders I am from this area, I’m not from the actual spill area. Sometimes all it takes is having beers with people and explaining where you’re coming from. People there are really nice. No one was ever mean except when the BP guy kicked us off the boat.

MB: I think really good films can come out of people going somewhere totally foreign to them and making a movie. I don’t want to be one of these “essentialist” people—I don’t believe in that, either. I think if you’re of something, it makes it easier sometimes. There’s a shorthand. It doesn’t make you a better filmmaker, though. Maybe quicker? There’s a bar where we shot, it’s where a lot of the shrimp boats land, it’s the coolest bar ever. We would go there and they would say, “Oh, are you from New York?” just because I’m from Mobile, Alabama and not from there. That’s already a class difference, and there are assumptions about who you are. So, even though I can convince funders I am from this area, I’m not from the actual spill area. Sometimes all it takes is having beers with people and explaining where you’re coming from. People there are really nice. No one was ever mean except when the BP guy kicked us off the boat.

H2N: Do you feel the film has a place as advocacy tool against BP? You look at a film like Blackfish and what that did to SeaWorld, but for me, this doesn’t feel that way. Was there a balance to be created between calling them to account versus telling the human story here?

MB: I feel that they should be held accountable and they are, somewhat. But I also think that we should look at our own culpability in being dependent upon oil and what we’re doing about that. One of the reasons I wanted to change the structure of the film after shooting for 18 months is that I wanted people to think about how they are a part of this, how we all are a part of the problem. I don’t think we should stand above the fray and say, “We shouldn’t be using oil!” and not thinking practically about how that would work; in the same way, someone standing up and saying, “Drill baby, drill.” There’s a lot of room in the middle, and it’s grey. I wanted the film to be a conversation and I wanted people looking away from laying sole responsibility at BP’s feet, but instead asking, “What’s the real problem?”

I do want to say, though, that BP has a terrible safety record and there is a reason this was a BP spill. They should be held accountable. But also, we all play a role in the system in which they operate when we fill up our car every day. We’re drilling in deep water, there’s danger there, but it’s all about convenience, right?

H2N: When you approached the survivors of the disaster and asked them to tell their stories, I imagine that was a difficult conversation and that it was tough to earn trust.

MB: That was the hardest part. I think they were really mistrustful of people and that they weren’t being heard. Initially, there was a concern that I might be a spy for one of the companies and not a filmmaker. So, it was hours on the phone, talking to their wives, because they were acting as the gatekeepers, because they didn’t know how the filmmaking process would impact their husbands and they didn’t trust me.

MB: That was the hardest part. I think they were really mistrustful of people and that they weren’t being heard. Initially, there was a concern that I might be a spy for one of the companies and not a filmmaker. So, it was hours on the phone, talking to their wives, because they were acting as the gatekeepers, because they didn’t know how the filmmaking process would impact their husbands and they didn’t trust me.

H2N: And you’re opening fresh wounds here. This wasn’t that long ago, so were you nervous about their reactions?

MB: I was nervous. We were very careful about our crew. We talked a lot to the wives about how to create a safe environments for their husbands and they were legitimately worried. One of our subjects, Stephen, would do this thing where if he got too uncomfortable he would just disappear. I saw him do that few times. I wanted to be sure when we shot them—we came a day early just to hang out because they were so nervous. We didn’t even know the day before we shot them whether this would even happen, because they were so uncertain and nervous. With Doug, he let us shoot outside the house, but wouldn’t let us in initially because they considered the house a safe space. So, we went back over and over and slowly built more and more trust.

I had to respect it because I could hear the pain. I could feel it, it was still so visceral while we we’re shooting. I remember the first day we were shooting Stephen, his wife told us he wasn’t really giving us the full story, so she pulled him aside that night and told him, “You have to tell them the truth. You can’t be in denial.” And the next day it totally changed, it was wild.

H2N: Can you talk about balancing the intimacy of these moments with the scale of the story, using archival footage of a huge disaster, and creating the tension here?

MB: I felt like the film needed it. And some of the stuff, like the Congressional testimony, was just gold; we had to use it or the story would be diminished. I don’t think anything about the way I make movies is too precious to change, though. I’ve only made two other movies, so it’s not like I’m some auteur. [MB laughs] We dealt with this in the editing room. I think my first instinct is to go vérité; with The Order of Myths, we had this one really long vérité cut that was all vérité, no interviews. And I feel like I always have to go through that cut before I get to the realization, “Actually, there has to be some framing…” [MB laughs] Usually, I am moved the most by vérité films, but sometimes, an interview can be the most powerful thing. I don’t have rules for anything.

MB: I felt like the film needed it. And some of the stuff, like the Congressional testimony, was just gold; we had to use it or the story would be diminished. I don’t think anything about the way I make movies is too precious to change, though. I’ve only made two other movies, so it’s not like I’m some auteur. [MB laughs] We dealt with this in the editing room. I think my first instinct is to go vérité; with The Order of Myths, we had this one really long vérité cut that was all vérité, no interviews. And I feel like I always have to go through that cut before I get to the realization, “Actually, there has to be some framing…” [MB laughs] Usually, I am moved the most by vérité films, but sometimes, an interview can be the most powerful thing. I don’t have rules for anything.

H2N: Did you receive any resistance from funders or BP on this film? We live in a litigious society, you have to be so careful.

MB: Yeah, we were super careful vetting everything in the movie for truth. As for being sued, I was more concerned that I didn’t get anything wrong. I showed this to people in the oil industry and asked, “Is there anything here that is misrepresentative?” Because I didn’t want it to be the kind of thing where they can spin it. I saw how they attacked GasLand and tried to point out all of these factual errors with that film, and I didn’t want to be seen that way. I felt this responsibility to have it defensible.

H2N: How do you feel about that, though? I mean, nonfiction films have a point of view, this is not news reportage, nor was GasLand…

MB: It’s not that I didn’t want to make a film like GasLand, more that I wanted to be sure the oil industry didn’t come after the facts in my film the way they did that film. Although who knows, they’ll probably come after the movie anyway.

H2N: “Ten Lies in The Great Invisible“…

MB: Exactly. I wanted to try to avoid that. I felt that we had to use facts in this story and they were very hard to find. If you try to research how many rigs are operational in the Gulf Of Mexico, it’s really tricky. Platforms are out there, some of which are connected, some of which are not, some linked to as many as 20 wells, some of which are working, some of which are not, so we could never quite find an answer. It seemed like no one knew, which I found very hard to believe. So, we were very careful with how we worded that in the film, because we wanted to show the scale of that and make it defensible.

MB: Exactly. I wanted to try to avoid that. I felt that we had to use facts in this story and they were very hard to find. If you try to research how many rigs are operational in the Gulf Of Mexico, it’s really tricky. Platforms are out there, some of which are connected, some of which are not, some linked to as many as 20 wells, some of which are working, some of which are not, so we could never quite find an answer. It seemed like no one knew, which I found very hard to believe. So, we were very careful with how we worded that in the film, because we wanted to show the scale of that and make it defensible.

H2N: What about you as a filmmaker, did your perspective change?

MB: I just think now about how I’m connected to all of it. Whenever I get on a plane to go promote the movie, I think about how hypocritical it is, how I live personally, how it trickles down to every single thing in my life. Maybe I’m just like that, anyway, but I didn’t know about all of these connections until I made the movie and it made me hyper-aware of comfort versus what we’re doing to the planet versus what we should be doing. The Climate March just happened, and I think there needs to be some sort of uprising, a sea change. I hope the film can help be a part of that and give… I hate to use the word “information” because that is a dirty word in documentary, but an understanding they may not have.

MB: I just think now about how I’m connected to all of it. Whenever I get on a plane to go promote the movie, I think about how hypocritical it is, how I live personally, how it trickles down to every single thing in my life. Maybe I’m just like that, anyway, but I didn’t know about all of these connections until I made the movie and it made me hyper-aware of comfort versus what we’re doing to the planet versus what we should be doing. The Climate March just happened, and I think there needs to be some sort of uprising, a sea change. I hope the film can help be a part of that and give… I hate to use the word “information” because that is a dirty word in documentary, but an understanding they may not have.

H2N: Another thing I think of when I think of your work is that you imply the need for social transformation—you don’t outwardly advocate for it, but you show us a world that seems to demand change. This shows a lot of respect for the audience.

MB: I think the audience is really smart. When I go and do a Q&A, they’re getting it. Everyone is seeing it and asking what they can do, examining their role. This is why i’m glad I partnered with Participant because they’re great at things like that. But I also think, well, I just saw CITIZENFOUR the other night and I don’t need someone to tell me what to do after seeing that movie. I can think of ten things to do after seeing that film. I trust my audience to watch my movie and think about their own lives and things they can do to have an impact. We’re not powerless in this situation, and I think that working together, we can make change.

H2N:You mentioned as a next step the possibility of making a fiction film. What’s the allure of fiction?

MB: Every film I want to try something different. But yeah, I don’t know. I’m writing a few scripts right now, but I love making documentaries. I love the mystery of it and that’s always alluring to me. We’ll see. I didn’t think I’d be making a movie about the Gulf Oil Spill four years ago, so who knows.

— Tom Hall